Internationally renowned Chinese performance artist Liu Bolin, who is currently in town for the Tokyographie 2018 photography exhibition, is a man who does not appear to rest.

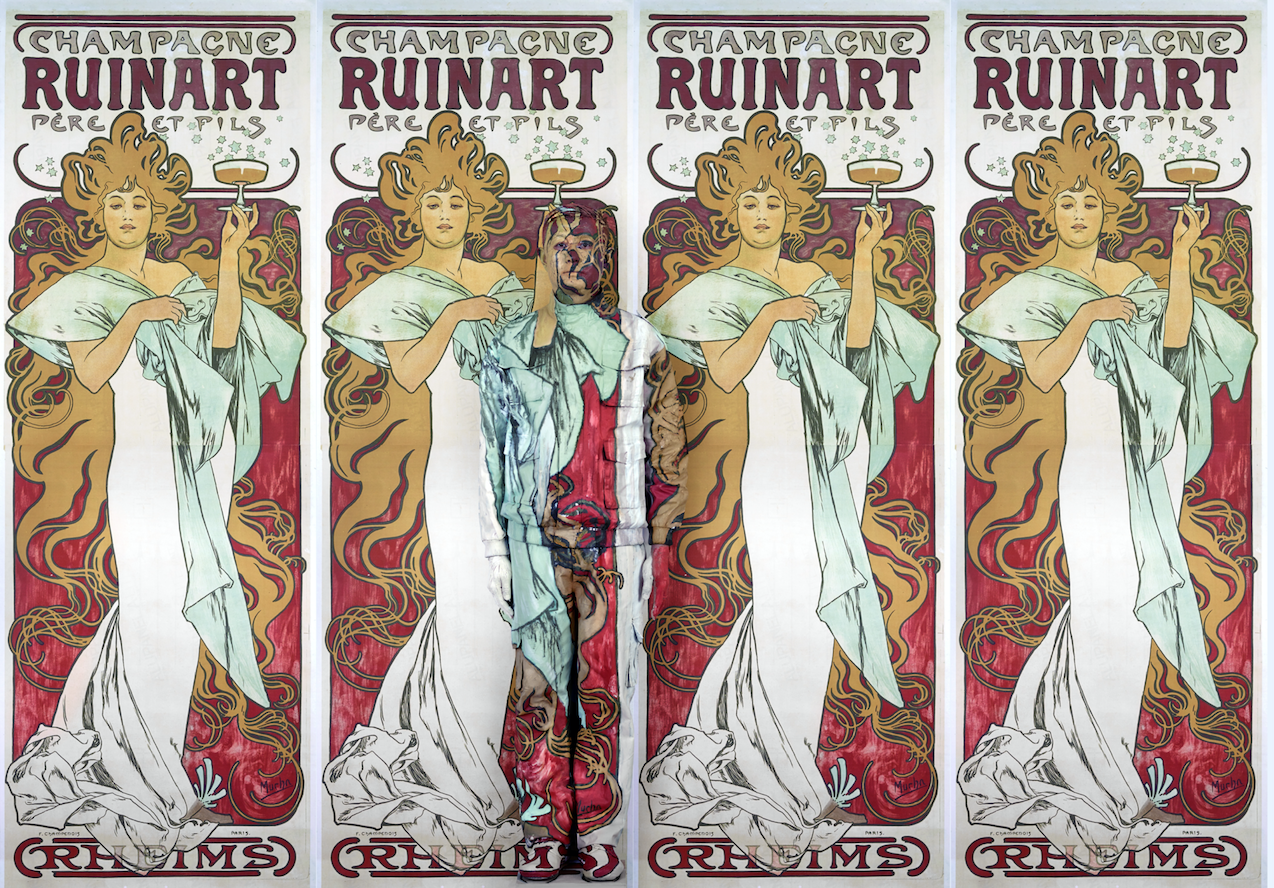

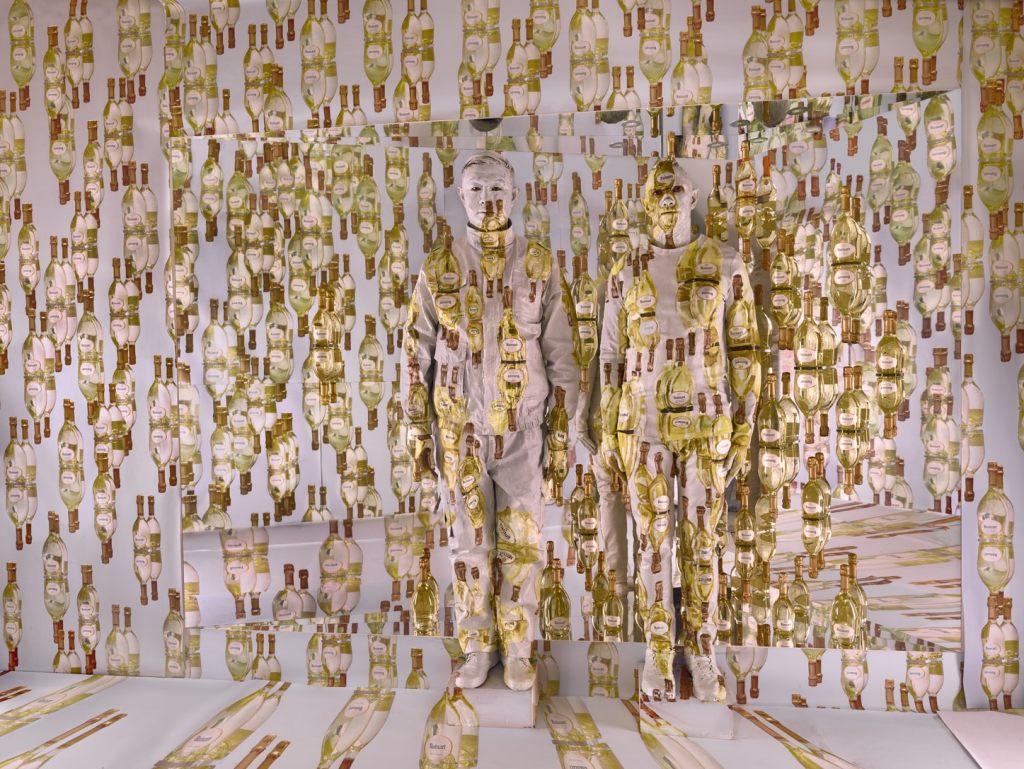

Bolin travels all over the globe to create installations in his signature style: using acrylic paints and a full body suit to literally paint himself into various scenes and cityscapes, he disappears into his surroundings in an effort to deeply probe the connection between humans and their societies.

Undertaking meticulous advance research, and working with a team of assistants, he stands still for hours on end during live painting sessions.

Liu Bolin, collaboration with Ruinart

Hiding in locales around the world in order to call attention to various social, political and environmental issues, Bolin’s numerous installations to date have included blending in to shelves of packaged foods and bottled water to spotlight the problem of chemicals and contamination; standing amidst a forest of barren trees to call attention to air pollution; and painting himself in to the ruins of the Suo Jia Cun artist village in his home city of Beijing following its destruction at the hands of Chinese authorities. The village had included his own art studio, which was the initial impetus for his disappearing art.

His works from recent years have also ventured into other mediums, including a livestream of Beijing smog from 24 smartphones attached to his body while he traversed the city, and his “Security Check” sculptures, through which he interrogates international airport body scanning procedures.

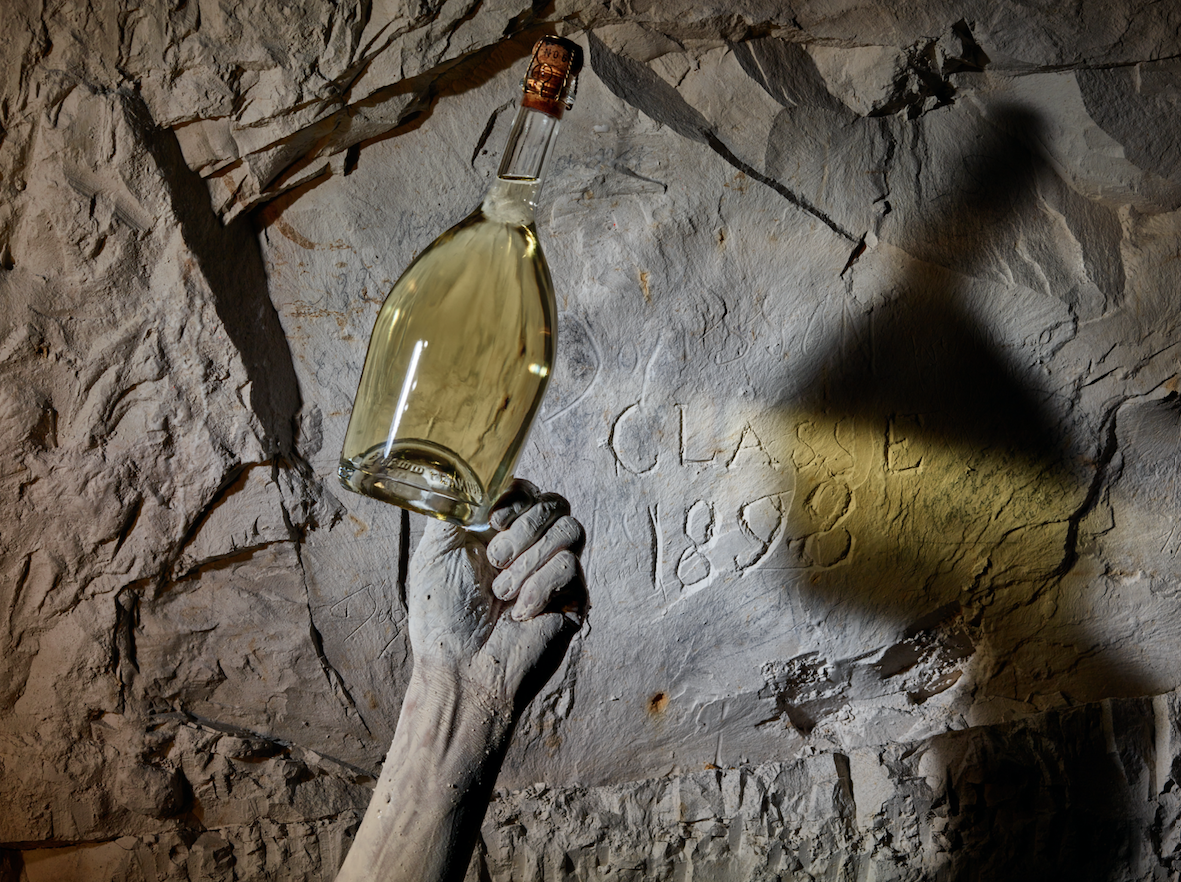

Bolin’s current Tokyo exhibition features a recent project undertaken at Ruinart in northern France – the world’s oldest Champagne house, which was inspired by a Benedictine monk and dates back to the 1700s. He produced eight pieces there, wherein he captured intimate moments together with workers in the cellars, fields and factory.

Liu Bolin in the Ruinart vineyard in France

The artist took time to chat with TW on a late autumn afternoon in a stylish Roppongi restaurant amidst what was an already frenetic schedule, and only the slightest hint of fatigue flashed across his warm eyes – evaporating nearly as soon as it appeared.

You have chosen some intriguing ways to hide yourself around the world. We assume your work aims to convey a message edged with commentary, and we wonder how you go about choosing your sites?

I am most interested in places where people have made – or are trying to make – changes in society through their own influence or actions. By going to such places and then hiding myself, I think it produces some pretty interesting tension and contradictions.

Why the Chinese military uniform in each of your installations? What is the symbolism?

First, this helps me to camouflage myself better. I guess I am a sniper of sorts. [Smiles] Secondly, my backup plan if I didn’t get accepted into art school was to join the military. So I guess wearing the uniform kind of enables me to achieve both dreams at the same time.

The initial inspiration for your work – being evicted from an artist village – shares similarities with the clearing out of peaceful protest camps around the world, including the 2011 Occupy movement. Do you think that your type of “artistry with a message” can help make a difference in today’s sociopolitical/ecological challenges, especially given the rise of authoritarian governments around the globe?

I think that people everywhere in the world are feeling quite strongly these days about various issues, whether social, environmental, or something else. And everyone has different ways of expressing that. Mine just happens to be through art. And of course, I always hope that it makes a difference.

Do you have some interesting or amusing anecdotes to share from your experiences working around the world?

One is from my recent project at the Ruinart Champagne cellars. Because we were underground and everything was lit up in orange, it was really hard to achieve the exact same color that would enable me to blend in to the background. I had never experienced anything like that before.

Another is when I did an installation with French artist JR at the Louvre in Paris. I ended up losing all of the digital images that we shot, and so we ended up having to reserve the museum for a second day. It started raining, but we went anyway. The rain stopped just when we arrived, and started again just after we left. It was really incredible timing. I felt like I had experienced something really unlucky, followed by something pretty miraculous.

What new insights were you able to get via your experience working with Ruinart?

I already had a tremendous amount of respect for the brand, given its 300-year-long history. And when I actually went there and was able to meet and work with the employees, I saw how passionate they were toward the company, which only made my respect deepen even further.

What about your impressions of Japan during your visit here?

When I went to Kyoto earlier in the year for the Kyotographie exhibition, it was my first time there. I had heard that the city was beautiful, but nothing really prepared me for just how gorgeous it actually was. I got the impression that the relationship between people and nature there has achieved an exceptional balance.

Standing without moving for hours on end is quite a feat. What if you get an itch or have to sneeze? Do you go into a trance-like state in order to be able to stay still for so long?

Well, first of all, I make sure not to eat or drink too much the day before an installation. And yes, I do go quite deep inside of myself while it’s happening. I guess you might say it’s something like a religious experience, where I have to have faith in my own mental strength. Most of all, though, it’s just about enjoying the process.

Some of your sites seem to have been quite daring and even dangerous…

First of all, when I was in Iceland two years ago (doing a piece for Moncler and being photographed by Annie Liebovitz), we were working onsite in a snowy landscape with icebergs. We had to finish the entire installation before 8am when the weather started to get really stormy. I stayed in place until the very last second, which was pretty scary.

The second time was six months ago, when I did a project in Pyongyang. We got advance permission and had secured a guide, but after we had finished photographing the last piece on the last day, a soldier came walking toward us. Our guide clearly felt unsafe, and ended up running away with my camera. We didn’t know what to do, so we just stood there watching.

I read that you changed your position for the first time ever by extending your arms outward while doing the Ruinart installation. Do you foresee other changes, or was this a one-off?

Actually, my signature style of standing still came long after I had started painting myself into backdrops. At first, I held lots of different poses, like sitting and squatting – but at some point, I realized that standing with my arms at my sides was the most symbolic and powerful way to spread my message. I changed my position at Ruinart because I felt a sudden inspiration to do so, and I suppose I may continue to make changes if that kind of feeling strikes me again.

Any future plans you’d like to share?

Although I am now known for this one particular style of artistry, in fact I am a sculptor in addition to being a painter and installation artist. I’d like my future exhibitions to include many different methods of artistic expression.

The Liu Bolin × Ruinart exhibition is on through December 9 at Block House in Harajuku as part of the Tokyographie international photography exhibition. For more information, see our event listing.