Archaeologists have found a monumental structure buried under the sands of Petra, according to a new study that drew on satellite imagery to scan the ancient city.

Satellite surveys of the city revealed a massive platform, 184ft by 161ft, with an interior platform that was paved with flagstones, lined with columns on one side and with a gigantic staircase descending to the east. A smaller structure, 28ft by 28ft, topped the interior platform and opened to the staircase. Pottery found near the structure suggests the structure could be more than 2,150 years old.

“This monumental platform has no parallels at Petra or in its hinterlands at present,” the researchers wrote, noting that the structure, strangely, is near the city center but “hidden” and hard to reach.

“To my knowledge, we don’t have anything quite like this at Petra,” said Christopher Tuttle, an archaeologist who has worked at Petra for about 15 years and a co-author of the paper.

“I knew something was there and other archaeologists – who have worked in Petra for the last, God knows, 100 years at least – I know at least one other had noticed something there,” he said. But the structure’s sides resembled terrace walls common to the city, he noted: “I don’t think anybody paid much attention to them.”

Tuttle collaborated on the research with Sarah Parcak, a self-described “space archaeologist” from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, who used satellites to survey the site.

Parcak said that she begins surveys “quite skeptical” of what they might find – they are working on sites in northern Africa, North America, Europe and elsewhere – and that she was surprised to find the monument “turned out to be something significant”.

“Petra is a massive site, and we chose the name for our article [‘Hiding in plain sight’] precisely because, even though this is less than a kilometer south of the main city, previous surveys had missed it,” she said.

Tuttle and a team took subsequent trips to measure and examine the site from the ground. There they found scattered pottery, the oldest of which suggests the site could date back to the time of Petra’s founding. “We’re always very cautious on this,” Tuttle said, “but the oldest pottery can be dated back relatively securely to about 150BC.”

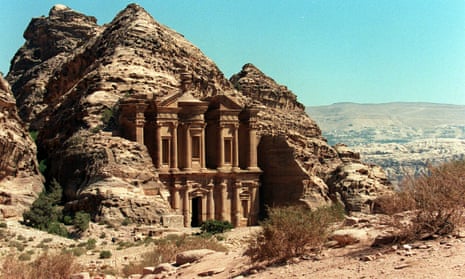

Petra was built by the Nabateans in what is now southern Jordan, while the civilization was amassing great wealth trading with its Greek and Persian contemporaries around 150BC. The city was eventually subsumed by the Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman empires, but its ruins remain famous for the work of its founders, who carved spectacular facades into cliffs and canyons. It was abandoned around the seventh century, and rediscovered by Swiss explorer Johann Burckhardt in 1812.

Along with the oldest Nabatean pottery, they found fragments that had been imported from the Hellenistic cultures who traded with Petra, as well as pottery of the eras when the Roman and the Byzantine empires took the city under their guard.

In the mountains, valleys and canyons surrounding Petra, Tuttle said, “there’s tons of small cultic shrines and platforms and these things, but nothing on this scale”. He said these sites, including a large, open plateau known as the Monastery and probably “used for various cultic displays or political activities”, are the closest parallel to the newly discovered edifice. “To be honest, we don’t know a whole lot about it.”

Those sites suggest that the structure was used for “some kind of massive display function”, he said. Unlike those other sites, however, the giant staircase does not face the city center of Petra, which Tuttle called a “fascinating” peculiarity.

“We don’t understand what the purpose [of visible shrines], because the Nabateans didn’t leave any written documents to tell us,” he said, adding: “But I find it interesting that such a monumental feature doesn’t have a visible relationship to the city.”

Nabatean shrines around Petra offer mixed clues about the ancient people’s practices. Like other Semitic cultures of the day, the Nabateans used an indirect, “aniconic” style to indirectly represent their divinities: carved blocks, stelae and niches. Sometimes there will be “an empty niche, just a carving in the wall, which the empty space itself can be representative or they would’ve had portable images”, Tuttle said.

But because they were in near constant trade with other cultures of the Mediterranean, the Nabateans also adopted figural representations. “Nabatean gods depicted as parallels to Zeus or Hermes or Aphrodite, and those kinds of things,” he said.

The researchers published their work in the Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. They said that while they have no plans at this time to excavate the site, they hope they will have the chance to work there in the future.

Parcak said that she expects “some pretty amazing discoveries over the next year” using satellites and sophisticated new techniques in south-east Asia “and other densely forested/rainforest areas”. A surveying technology called Lidar, for instance, has uncovered sites in remote forests in Central America.

“This technology is not about what you find – but how you can think about things like settlement scale and ancient human-environment interactions more broadly,” she added. “What happens when you can truly map the near-surface buried features for an entire site? I’m excited, but we need to think about the implications of having all this technology at our fingertips so we can use it responsibly.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion