Mirwais Ahmadzaï is trying to sum up his frequent collaborator Madonna. “You know bullfighting?” he begins ominously. “It works because the bull is so powerful that you have to weaken it.” Right. “Look, I’m not comparing Madonna to a bull,” he quickly adds, “but she was so powerful at that time.”

The Parisian, who turns 60 on Friday, peppers our 90-minute phone call with similar flights of fancy, ponderously linking Brexit to Baudrillard and dropping situationist truth bombs. And he has witnessed that power up close. A cult musician in France since the late 70s, and cited as an influence by the likes of Air and Daft Punk, Ahmadzaï was plucked from the sidelines by Madonna in 1999. He helped coax out her most experimental era, bolting his brand of heavily filtered, minimalist electrofunk on to the superstar’s 11m-selling album Music. His sonic fingerprints were all over two singles that immediately slotted into the already heaving Madge canon: the delicious electro-bounce of the title track and thigh-slapping country curio Don’t Tell Me.

Three years later came the politically-minded American Life, a divisive flop, before Ahmadzaï seemed to disappear into the pop wilderness. However, the pair reunited for last year’s album Madame X. How did she coax him back?

“Very simple – she called me,” he says. “It was after Donald Trump’s election and there were so many celebrities who were saying, ‘I’m leaving America [if he wins]’ and none of them left except her,” he says, referring to Madonna’s relocation to Portugal. “That’s why I have to defend her. It’s cool to have the courage of your convictions.”

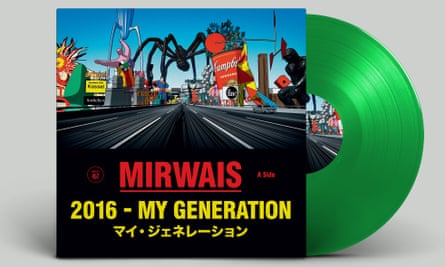

Perhaps Madonna recognised that in Ahmadzaï, too. Twenty years after the release of his breakthrough solo album, Production, he’s back with a new single, 2016 – My Generation, and a forthcoming album, The Retrofuture. A mainly instrumental track, all chunky synths and trademark acid bass, 2016 – My Generation comes with an eye-popping animated video from Oscar-winning director Ludovic Houplain that offers up a panoramic view of modern life, from porn addiction (one section features skyscraping ejaculating phalluses), to the rise of the far right.

The song, Ahmadzaï says, was finished three years ago, but was sidelined when Madonna came calling again. He returned to it after he came across a Trump interview from before he was elected president in 2016 in which he refused to condemn “the former KKK grand wizard” David Duke. “Then, a few weeks ago, [the president] was asked if he condemned white supremacists and he said he didn’t know. So he hasn’t changed. That’s why I wanted to release it now.”

The Retrofuture, due next spring, will be his third album in 30 years, a work rate that reflects not just his disdain for the current musical landscape – “It’s always been 80% crap and 20% good, but in these last 10 years [the latter] has been only 5%, sometimes 2%” – but also something more esoteric. “You know the black monoliths that appear in Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey?” he says. “Well, they appear when there is change happening in society. So I think it’s the right time for my album. Like the monoliths, I like the idea of making things when there is change.”

The “chaos” of the global pandemic helps, too. “For people it’s terrible – unemployment, the social crisis – but for music, maybe there’s some good to come out of this period.” Despite asking, “Do you like to boogie woogie?” via Madonna’s Music, he’s surprisingly unfazed by the problems facing the clubbing industry. “Who wants a dance record? There are no clubs any more.” So, you don’t make dance music? “I’m a hybrid. People try to define me, but I don’t like to be one thing.”

Ahmadzaï’s outsiderdom was defined at a young age. Born in Lausanne, Switzerland, where his Italian mother met his Afghan father, the family moved to Kabul before relocating to Paris when Ahmadzaï was six. “Coming from Afghanistan in the 60s wasn’t like coming from Germany or USA, it was like coming from Mars or Jupiter,” he laughs. His heritage also meant he was constantly searching for home: “I’m what they call in France a métis, a mixed person. If I go to Afghanistan they say, ‘You’re an outsider’, and if I go to Italy it’s the same.”

Fuelled by what he called the “reign of silence” instigated by his family’s loneliness, Ahmadzaï became obsessed with music, specifically Jimi Hendrix. He got his first guitar at 12 and, in 1978, formed new wave group Taxi Girl, aged 17. “Since I started playing guitar, my goal was to be in a band,” he says, “to be part of a family.” Influenced by the likes of Blondie, the Stooges and Kraftwerk, Taxi Girl were often kept on the fringes by a French music industry suspicious of their youth.

“In the UK, young artists are celebrated, but in France you have to wait until you’re 30 at least,” he says. “People didn’t get it. For me, we were at the same level as bands like Magazine or the Stranglers.” For a while Taxi Girl dabbled in politics, with their late keyboard player Laurent Sinclair dating Joëlle Auborn of far-left terrorist group Action Directe. “We were very politically aware, but music was better. Because when you start getting really into politics you have to commit.”

Drugs were an issue. Their drummer, Pierre Wolfsohn, died from a speedball – a mix of heroin and cocaine – in 1981, while both Sinclair and singer Daniel Darc, who died in 2013, suffered addiction. “At that time all the trendsetters were doing heroin,” Ahmadzaï says. “I started doing drugs very young, but two years after starting Taxi Girl I stopped. The others said I was the most intelligent,” he adds with a rueful laugh. The band ended in 1986, but their influence grew. “For bands like Daft Punk, they only know success. Taxi Girl, we were a cult band. I’ve had the full spectrum in my career – from a lost band on one hand to Madonna on the other.”

For most of the 90s, Ahmadzaï meandered through different genres, from acoustic chamber pop to an unreleased jungle album. In 1999, having signed his independent label, Naive Records, to Sony in the UK, Ahmadzaï was looking for a US label to release Production, a sleek electronic opus that fused stuttering beats with acoustic guitar and Auto-Tuned vocals. Impressed by the way Madonna’s Maverick label had handled the Prodigy in America, Ahmadzaï asked his photographer friend Stéphane Sednaouï, who had directed Madonna’s Fever video, to send lead single Disco Science to her manager Guy Oseary.

“He loved it and passed it on,” says Ahmadzaï. “When she heard it she said, ‘This is what I want to do’, so we tried it out.” Was he a fan of her work at that point? “I don’t know if you know the situationist movement,” he says, “but one of the things they said was break the link with the hero. I love Madonna but I wouldn’t say I was a fan. I didn’t have the fan attitude.”

Their early sessions were complicated by a language barrier. “She always says that I couldn’t speak English,” he laughs, “but she speaks with an American accent and very quickly. She’s very impatient – everyone knows that.” After Music’s playful electro came the more left-field folktronica of American Life. It got off to a bad start with the lead single and title track, which featured Madonna rapping in toe-curling style about her yoga classes, coffee-drinking habits and private jet.

“Yeah, we had a big debate about the rap,” he sighs. “We did another version where it’s more integrated into the mix. But I like to be provocative, which is why ultimately I didn’t fight her on it.” His voice softens, something it does a lot when discussing Madonna. “She just loves what she does. Even with Madame X, and working with [26-year-old Colombian singer] Maluma, people were like, ‘She shouldn’t do that.’ She just doesn’t care. If the reaction wasn’t good, it was OK.”

By the time Madonna executed a storming comeback in 2005 with the Confessions on a Dance Floor album, Ahmadzaï was burnt out. “I was supposed to do a big part of Confessions, but I had to leave,” he says carefully. “I worked on two tracks, but we were meant to do about five or six.” He’s cagey about why he left. “To be honest with you, if it had been today I wouldn’t have. I had some issues to resolve.” Besides, he was never supposed to be an underground producer for hire: “I was an artist before Madonna. This is one of the secrets of our relationship. I’m an artist too, and she knows that.”

Like all artists, Madonna included, Ahmadzaï enjoys contradiction. A self-confessed cult musician with a superstar on speed dial, he’s chosen a culture-destroying global pandemic to return to music. Not only that but he’s about to release a conversation-starting song and video, taken from an album featuring established names such as Richard Ashcroft and Kylie Minogue, as part of some sort of experimental protest.

“I do not care about streaming or video views,” he says. “We are aiming for zero views if possible, or zero streams.” Right. “I want to change the way we release records. It’s just a drop in the ocean, but it’s good to provoke.”