In 2016, while on a working trip to Helsinki, the American photographer Alec Soth underwent what he calls “a full-on mystical experience” that precipitated a year-long sabbatical from work. “It was pretty far out, to the point where I find it embarrassing to talk about,” he says. When I press him, he recounts the story of sitting down by a lake to meditate, then having “this sudden realisation that everything in the universe was connected”.

He pauses to gather his thoughts. “I know it sounds hippy-dippy, but it was incredibly intense. I was tearful and simultaneously filled with this almost overwhelming sense of joy.”

He had just arrived in a foreign country after a long-haul flight – might it have been down to lack of sleep, jet-lag, the heat? “I guess so,” he says. “But whatever happened in that moment, the fresh air or the light or brain chemistry, allowed me to experience reality closer to what it actually is. The idea that the self was somehow separate seemed utterly absurd, an illusion.”

For the ensuing year, Soth, who lives in Minneapolis, says he did “almost nothing”, which, given his previously prodigious work rate – editorial commissions, travelling workshops and talks as well as producing books and exhibitions – must have been quite a gear shift.

“Not really,” he says. “That’s what was so liberating. For a while, I was making small creative gestures for myself. It felt like I was learning anew how to engage with work, with my life. During that time I couldn’t have cared less about an audience. I remember thinking: I’ve been happy before and I know how to be happy, and it is not to do with chasing after creative expression.”

And yet here he is, with a new book about to be published and a promotional campaign lined up. “I know, I know,” he laughs. “I’ve come to an acceptance of both. But I am certainly less ambitious and less manipulative than I was, and I think that is evident in a good way in the new work.”

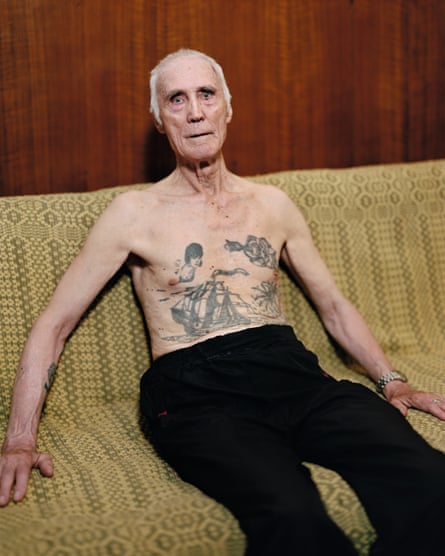

The book in question is I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating, the title taken from a line in the Wallace Stevens poem Gray Room. As anyone who follows him on Instagram knows, Soth is big on poetry, seeing it as akin to photography in its attempts to evoke the ineffable. Towards the end of the book, there is an Emily Dickinson quote about birds and blossoms, both of which feature in the preceding pages alongside an embrace of painterly, often pastel colours. For all that, the shift in tone, both formally and atmospherically, is a subtle one and there are several portraits that are identifiably his work – a young man curled up on a bed clutching a sprig of herbs, an old man on a sofa, his chest marked by old-fashioned tattoos.

The interiors, too, in their melancholy neglect, occasionally hark back to his breakthrough book, Sleeping By the Mississippi (2004), a landmark publication which established his reputation as the leading light of contemporary documentary photography. A sense of romantic melancholy has been a constant of Soth’s work since that stellar debut, reaching a sustained mood in 2014’s elegiac Songbook, the subtext of which was the death of small-town American communities.

This time around, Soth’s subject matter is both more intimate and more elusive: the ways in which a domestic interior can illuminate the inner character of those who created it. Here, even the still lifes are portraits of a kind. “I guess I wanted to make quieter photographs,” he says. “It was also about the thrill of curiosity – what books are on the shelves, what that tells you about the person. You can figure out a lot about someone from their living space.”

In the wake of his Blakeian epiphany in Helsinki, Soth also found himself thinking a lot about the power dynamics of portrait photography. “When I started out I had so little power because I was so shy and awkward,” he says. “And often people responded to that in a positive way. Then, as I did more editorial, I got more power and I would push things in order to get a better picture. Now, I want to undercut that somehow by being a bit more sensitive, less pushy.” Has he succeeded? “Not always, but there were times when I was shooting this series that I could have definitely made a more powerful picture by manipulating the situation. I’m good at that in a charming way, but it seems less interesting to me now. I’m still leading the dance, but I’m not pushing people around the dance floor.”

In late April last year, I received an email from Soth to say he was arriving in London to continue a project he had been working on in the US. “I’m looking for both interesting people and interesting spaces,” he wrote. “They can be male or female, young or old, rich or poor. The main thing is to have an intimate encounter that is visually strong.”

So it was that, for a couple of days, in London and Hastings, I watched Soth work up-close as he photographed people I knew who lived in “interesting spaces”. It was an illuminating experience, though only one exterior photograph, Susanne’s View, London – the most pastelly photograph in the series – made it into the book.

Soth uses a large glass plate camera on a tripod. The process is unwieldy and requires a degree of patience from the sitter, who has to remain still while Soth sets up the shot, mysteriously disappearing for extended periods of time under a large blanket. It seems, I say, an oddly Victorian way to work, one more suited to the great outdoors.

“Very true,” he says laughing. “But it’s beautiful under that blanket. Getting to stare closely at someone’s eyebrow as you shift the plane of focus. And, the world is upside down! I’m grappling with technical challenges that create this wonderful nervous energy.”

So, what exactly is he doing under there? “Basically, trying to get things in focus. It’s a camera built for Ansel Adams to photograph the American deserts and prairies and I’m using it in confined interior spaces. It’s demanding but nothing else comes close when it comes to capturing light and texture. It ’s almost sensual the way it caresses surfaces.”

In the book, an intimate portrait of the reclusive photographer Nancy Rexroth is a study of self-containment and vulnerability. Her neutral gaze is echoed by the more intense gaze of her cat, which is just visible peering over her shoulder as she lies on her side on a bed. “If you look closely, one of Nancy’s eyes is way out of focus,” says Soth. “I was concentrating on getting her other eye and the cat in focus. That’s what I tend to do, focus in on an eye or even an eyebrow. It’s incredibly intimate.”

I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating is a slim book, just 35 photographs whittled down from a series of 75. “Unlikely as it seems, my ambition was to somehow not make a project, and to not make a narrative photobook. I didn’t want to turn it into something bigger,” says Soth. “It was more about keeping a certain modesty, trying to incorporate a little more of the sensitivity I felt when I was on my retreat from work. Photography is not essentially a sensitive medium, but I’ve come to realise that sensitivity matters. It really does.”

I Know How Furiously Your Heart Is Beating is published by Mack (£50)