Too good to be true: that is the art of the German photographer Andreas Gursky. His monumental pictures of our world – magnificently orchestrated, gorgeous in their super-saturated colours – are so improbably detailed you can view the sea from outer space and somehow see tiny people far below on the shore. Everything is in equal focus, and every photograph holds more than the eye can see. That they are not real is surely obvious at first glance.

Or is it? This remains the crux of his work. When Gursky’s picture of the Rhine as a band of silver light between parallel grass-green stripes became the most expensive photograph ever sold, in 2011, many people didn’t realise it had been digitally altered. Gursky removed dog walkers, trees and an entire power plant for the sake of abstract beauty, updating German Romanticism with his geometric sublime. But the photograph still partook of the reality it depicts; it is the Rhine, and yet it is not.

At 63, Gursky has done more than any other contemporary photographer to expand the medium’s vocabulary. His highly rhetorical visions may be as much as 12ft wide, as remote as possible from the casual snap; they may double, tile and collage multiple images into vast panoramas – jammed trading floors and hurtling highways, corporate atriums and industrial farms, mass tourism and skyscraper cities, each lonely window a glittering pixel by night. Think of a frantic stock exchange or a 3am hyperstore, and his work springs to mind. Our world has come to look like a Gursky.

It was not always thus, as this lifetime survey reveals in almost 70 works handsomely installed in the refurbished Hayward, reopening next week for its 50th year. It is a perfect match: outsize images in chasmic galleries (the viewing conditions, alas, remain gloomy despite a few extra skylights). You almost expect a photograph of crowds seething round this post-industrial bunker. But the 80s landscapes that made Gursky’s name turn out to be pastoral: Sunday fishermen deafened by the nearby autobahn, beauty spots marred by telegraph wires, a lone hiker dwarfed beneath a concrete flyover. Austerely composed, yet oddly sentimental.

But in 1991, Gursky hit upon the idea of using computer software to manipulate a photograph of a Siemens factory, multiplying the wires, bales and dangling cables so the human beings are scarcely visible. The picture is almost illegible in its micro-detail, yet uniformly sharp and clear. Gursky had come up with the all-over focus.

And this has been his metaphor, pretty much, ever since: the idea that everything is happening all at once all over the world to an incomprehensible degree. The supermarket shelves are so densely arrayed with generic objects they become formal abstractions. The airport departures board flashes up endless destinations. In the stock exchange there is no human narrative, only a shifting pattern of frantic figures; and there they are again, repeated ad infinitum on little computer screens at the centre of the picture.

There is a spacey uniformity to Gursky’s aesthetic that is both sumptuous and numbing. Abstract at a distance, figurative close-up, his pictures are simultaneously beautiful and bloodless. You miss the camera’s potential for chance observation and discovery in these intensely premeditated scenes. And all the artifice – involving planes, cranes, satellite cameras and elaborate software – what’s more, may be put to the service of surprising banality.

A classic Gursky, for instance, is the epic Paris, Montparnasse (1993), showing all 750 flats in the city’s largest apartment block. Made using multiple shots taken from two different vantage points, this architectural vision does away with foreshortening and gives equal emphasis to every window. Much has been written about its creation. But in fact it offers nothing more than the actual experience on the street. The viewer searches the picture in exactly the same way as the reality, looking for the telling quirk – an easel, a mannequin – among all the windows full of standard lamps and plant pots.

Is this democracy, or generalisation? Too often Gursky tends to the latter, lumping everyone and everything together. To witness two hundred Chinese women making basket chairs in dismal conditions is to see mass-production in action, to be sure, but where is the human being in the crowd? People, for him, are ant-like against nature, the concrete city, globalisation. At a rave, they are just units of energy, turning this way and that in repetitive collage (an image that pretends to show a single moment, but self-evidently doesn’t). “I am never interested in the individual,” Gursky has said, “but in the human species and its environment.”

Behold! That is what his supersized images say. But what do they want us to notice: miles of factory-farmed cattle, prairies of plastic bags, deserts of Mexican waste (all unnecessary multiplications)? Confronted by the Great Pyramid at Giza, he sees what we all see: the eye-filling facade of a million blocks. At the industrial port, he witnesses industrial numbers of ships. These images range from platitude to tautology.

The ambiguous relationship between reality and fiction is at issue all through the show. Sometimes the manipulations are visible (the inmates in a panopticon prison don’t quite fit their cells). Sometimes they feel suspect.

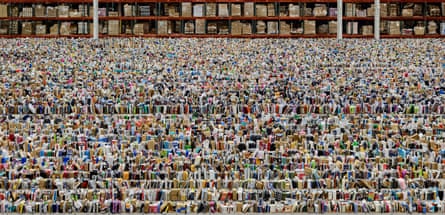

The largest work here shows the Amazon warehouse in Phoenix, Arizona: a tumultuous landscape of objects ordered by some mysterious Borgesian algorithm – atlases next to nappies, grammar guides with bath mats – to bewilder the mind and eye. Except that there are no pathways for the poor benighted workers (who aren’t shown in any case). Artifice undermines evidence.

Just as one searches for the individual in Gursky’s masses, so one looks for the artist’s own temperament in his work. It is most present, it seems to me, in his strongest works. In that beautifully sombre Rhine, for instance, rolling away into the imagination, and in a marvellous photograph of a Prada store got up to look like a minimalist white-cube gallery with lighting by Dan Flavin and shelves by Donald Judd, all to flog some mingy overpriced garments wittily deleted from the picture.

Gursky’s sense of humour, indeed, is too often underplayed. But you can see it at the Hayward in a gigantic fiction of four German chancellors sitting before a big red Barnett Newman canvas. Angela Merkel in shrill yellow turns to Gerhard Schröder, who is puffing on his customary cigar. German smoke drifts like Romantic fog across this triumph of American abstract expressionism, a wonderful parody of international politics and culture.

But the show’s masterpiece is unlike almost anything Gursky has made before. It is a new work, a single shot of some prefab houses skimmed on a mobile phone while driving through Utah. The photograph registers the speed of the car racing through the landscape – and modern life – in all its random glitches and blurs. At the same time, the houses look perilously ephemeral against the ancient mountains behind them. This fragile little thing, a spontaneous and disposable shot, is enlarged to the size of a cinema screen – a monumental homage to the mobile phone and the outsize role it plays in depicting our times.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion