In 1999, Alec Soth set out on the first of a series of road trips along the Mississippi, travelling from his hometown of Minneapolis, which lies close to its headwaters, to Louisiana in the deep south. Eschewing the detached approach favoured by many of his contemporaries, Soth made evocative portraits of the often isolated individuals he encountered along the way, from loners to convicts, from sex workers to self-styled preachers. He saw the river as both metaphor and dreamscape, describing it as “a worn and faded place” that he photographed “optimistically, even with love”.

From a distance beneath a glowering sky, he shot the shack in Dyess, Arkansas, where country star Johnny Cash was raised; and in Little Falls, Minnesota, he captured the boyhood bed of the aviator Charles Lindbergh. Both homes are now sites of pilgrimage, arbiters of the still resonant mythology of the American dream of self-willed success. A quotation from Lindbergh – about how he slept and dreamed with his eyes open while making his epic crossing of the Atlantic – provides the epigraph to Sleeping by the Mississippi, the acclaimed book of photographs Soth’s wanderlust gave rise to. A selection of the work will be shown in London, to coincide with a reissue of Soth’s classic book, first published in 2004.

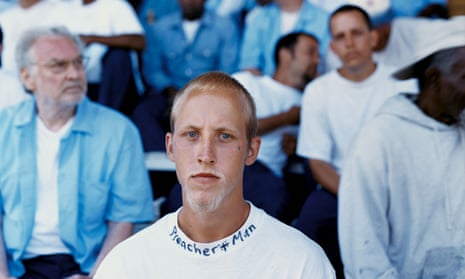

The photographer’s quiet charm gained him access to Louisiana State Penitentiary, where he made an arresting portrait of a youthful prisoner with the words “Preacher Man” etched on his white T-shirt, and to a brothel on Elvis Presley Boulevard in Memphis, where he photographed a young sex worker called Sunshine, “the saddest person I met in my travels”. Religion, too, is a constant presence in the book, from the image of a convict work group standing by a huge memorial cross in Kentucky to the portrait of Bonnie, a woman holding a photograph of a cloud that resembles an angel. Soth photographed people and places along the river with a patient attentiveness, using an unwieldy plate camera on a tripod, the slowness of his approach echoing the pace of life he encountered.

Sleeping by the Mississippi was Soth’s first book, but its maturity is breathtaking. It is haunted by the ghosts of an older, stranger America, one that was brought most vividly to life by Mark Twain in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. More palpable for Soth, though, was the looming presence of his photographic predecessors – such as Walker Evans, Robert Frank, William Eggleston, Stephen Shore and Joel Sternfeld, who was his teacher at the University of Minnesota.

Did he feel the weight of that great documentary tradition on his shoulders as he set out along the river? “Not as much as you might think,” he says. “You have to understand that, back then, I didn’t have a career as a photographer. And, what’s more, I had determined it wasn’t possible to have one. So I decided, ‘Let’s just do what I want to do without too much thinking about influences and tradition.’ It is only over time that I have come to recognise the nuances that make me different.”

Some of those nuances, most notably his way of evoking broken lives in a quietly powerful way without resorting to either romanticism or studied detachment, are undoubtedly rooted in his midwestern sensibility, which he once described as “dark and lonely”. Nevertheless, he possesses a seemingly instinctive ability to gain the trust of his subjects, several of whom recounted their dreams for him as he set up his camera. Peter, who lived on the river in a houseboat, dreamed of having running water. Lenny, a construction worker who moonlighted as an erotic masseur, dreamed of living to 100 and still looking youthful. A young Mexican immigrant named Ismael said his dream was “to be valued in America the way I would be in Mexico”.

The discontent that underpins much of the American way of life courses through the book like a dark undercurrent. “I did have the sense early on that I wasn’t a big social statement photographer,” says Soth, “and I certainly didn’t want to make the authoritative statement on the river. It was more a case of wanting to wander and have an experience. Given that the Mississippi has been burned into the American imagination since Twain, I did think that as a subject it was almost embarrassingly obvious, but weirdly it had not been done that much.”

The republication of the photo book alongside the exhibition marks Soth’s reemergence after a period of self-reflection. Last year, he decided to “withdraw slightly from all my other activities to reconnect with the very basics of why I fell in love with the process of photography in the first place – the play of light on an object”.

It is not hard to see why he needed a break. Now 47, the Minneapolis-based photographer has published 25 books and had over 50 solo exhibitions worldwide since the success of Sleeping by the Mississippi, while also establishing a reputation as a contemporary image-maker. He runs an independent publishing company LBM (Little Brown Mushroom) and, for a while, was an inveterate blogger and teacher. He describes his travelling Winnebago Workshop as an “art school on wheels”, a place where people who did not study photography can learn the craft free of charge.

Soth’s working practice, like his photographs, blends the traditional with the new: several of his publications – including 2008’s The Last Days of W, comprising photographs he took during George W Bush’s presidency, and his Lonely Boy Mag series, which pastiches men’s vintage magazines – were published in small runs and disseminated online or through specialist bookshops. Others, such as his LBM Dispatch series, take the form of printed newspapers filled with images from his travels in Ohio, Michigan, Colorado, Texas and Georgia.

What precipitated his sabbatical from all this feverish production? “I think that with the success of my first book, it felt suddenly that my ticket had been called and I was off to the races – and there was this feeling for a long time that I couldn’t stop or it would all come crashing down. I just felt I needed to be out there all the time on this ego treadmill. I’ve finally seen though all that garbage and become much more relaxed about myself and my place. Plus, I recently read a quote by Donald Trump about never stopping. He equated stopping with failure rather than, say, self-reflection, which kind of says it all really.”

Soth’s best work has always had a melancholy undertow. In 2006’s Niagara, he cast his gaze on the Falls, portraying a site of “spectacular suicides and affordable honeymoons” where the dream of romance is offset by a soul-sapping drabness and vulgarity. Darker still is Broken Manual, from 2010, in which he sought out recluses and latter-day hermits, the loners who live off-grid in America’s backwoods and wildernesses. His most recent series, Songbook (2015), looked at the disappearance of small-town community, its narrative punctuated by lyrics from songwriters of the old school – Jerome Kern, Lorenz Hart, Johnny Mercer.

His America is both recognisably real and oddly dreamlike, a place that seems to be fast fading from view even as he chronicles it. “For me, it’s still about going out into the world with a camera. America can constantly surprise you with its warmth and openness. That Whitmanesque element is still there.”

Surely, though, the US has changed dramatically since he made Sleeping by the Mississippi. The book may yet become an elegy for a continent once again riven by the old tensions of race and religion, but also the new post-truth politics of Trump-style Republicanism. “Well, even though I live in the liberal bubble of Minneapolis, which is like the San Francisco of the midwest, I’ve always been a big defender of middle America. That’s there in the photographs, too. I’ve met many born-again Christians along the way and found them to be wonderful people, smart and interesting, but this last year I’ve been forced to really question my own thinking, given that it’s the Christians who are defending him. But, you know, there always was that dynamic, especially in the south, where there is a willingness to say things more publicly. The whole race issue was more out in the open there, but now it really feels like it’s horrendous everywhere.”

How did it feel to revisit the Mississippi work, given that it was such a pivotal moment in his career? “Well, I’m still attracted to similar subject matter,” he says, “to people and landscapes that somehow speak of another America. As I have tried to figure out who I am as a photographer, I have learned that I do well when I don’t try to run away altogether from cliche or romanticism. I would rather engage with those elements through my work than erase them from it. The big difference is that now I’m aware of other people seeing my work and discussing it. That was not the case when I was making Sleeping by the Mississippi. Back then, I was just a local Minnesota photographer with nothing to lose.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion