On entering Botticelli Reimagined when it opens this week you could be forgiven for thinking that you’ve come to the wrong place. Rather than communing with a series of sad-eyed Madonnas, gently curving Venuses and light-as-puff angels, what you will actually be faced with, at least in the opening room, might best be described as a splatter of exclamation marks, dense and contemporary.

Adjust your eyes, though, and you will see that Venus, the Madonna and various feathered functionaries are indeed all present and correct, it’s just that they have assumed new and disconcerting forms. There is Tomoko Nagao’s take on The Birth of Venus from 2012 for instance. Instead of Botticelli’s lyrical marine pastoral, here is a graphic collage done in “superflat” style, the kind of thing generally associated with manga or anime. Airline tickets from easyJet, till receipts from an Italian supermarket chain and discarded packets from Barilla, the ready-made pasta people, pile up in dirty drifts. The artist’s native Japan is, in turn, referenced by a Hello Kitty, a pot of Shiseido skin cream and a trampled games console. True, there is a Venus of sorts rising from this sea of industrial detritus, but she is pert and provisional, with cartoon saucer eyes and no mouth. Her job is to witness, without comment, the ugly fallout of global consumer desire.

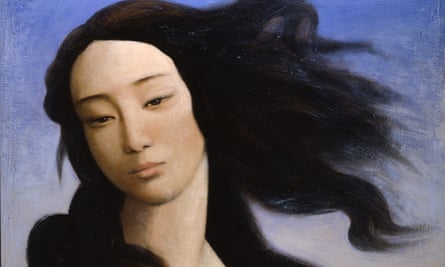

It gets stranger. In Venus, After Botticelli (2008), the Chinese artist Yin Xin reimagines Venus as an oriental woman. The dissonance of a raven-haired, almond-eyed goddess of love is a reminder of how invested we continue to be in a Botticellian ideal of female beauty, both inside and beyond the frame: tall, slender, curved, with porcelain skin, light eyes and the signature golden hair of northern Europe. Pushing this pin-up prettiness to its uncomfortable limits, the American photographer David LaChapelle has staged the Rebirth of Venus (2009) using a model whose bullet breasts, glycerined limbs and baby-blond wig lend a disturbing porn-star vibe to the whole proceedings.

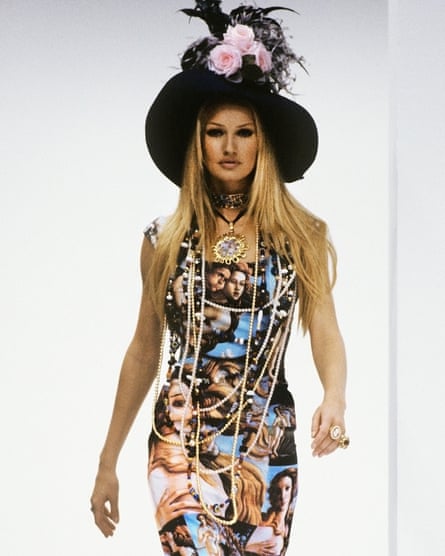

Elsewhere in the first room of Botticelli Reimagined, Venus does occasionally deign to get dressed. Photographs from Dolce & Gabbana’s spring/summer collection of 1993 are a reminder of how the Italian design duo once photo-printed sections from the goddess’s face and body on to fabric. This was then made up into a suite of dresses and trouser suits, modelled by catwalk Amazons who brought a strutting fierceness to imagery originally created to convey the pliant loveliness of the naked female form. Meanwhile, just to prove that there is no end to Botticelli’s capacity for reinvention (or, strictly speaking, appropriation), a publicity still from 2013 is a reminder that Lady Gaga chose to wear the D&G Botticelli dress while promoting her single “Venus”, in effect turning herself into a quotation of a quotation.

It is, then, Botticelli’s capacity for replication – or rip-off – that lies at the heart of this exhibition. The clue, really, is in the title: “Reimagined”. There is, suggests co-curator Mark Evans, something about the 15th-century’s artist’s expressive linearity and perspectival flatness that makes him eminently adaptable to modern technologies of reproduction: “He goes nicely on a T-shirt.” Moving the argument up a notch from the gift shop, you could say that Botticelli’s visual ubiquity means that The Birth of Venus, hotly chased by Primavera, has become the shorthand for a certain kind of middle-brow aesthetic. Whenever you see a fragment from one of Botticelli’s greatest hits – on the cover of a popular art guide, or advertising a Tuscan mini break – you know that you are in the company of culture.

Still, as Evans and his co-curator Ana Debenedetti make clear, this is not a show exclusively concerned with the artist’s post-mortem proliferations. Parsing TS Eliot’s comment that “when a new work of art is created ... something ... happens simultaneously to all the works of art which preceded”, they set about mining the many re-versions of Botticelli’s work for clues as to what it might say about its production in his time. What was it about Botticelli that has made him such a fertile resource for other artists down the centuries? In response to this question, the exhibition is organised as a reverse time tunnel: we start with contemporary riffs on Botticelli and move through his late Victorian popularity. It is only in the final room that we come face to face with the work of the man himself.

Or do we? Many of the objects in the closing part of the exhibition turn out to be attributed to “Botticelli and workshop”, or simply “Workshop of Botticelli” or even, in a final distancing shrug, “Follower of Botticelli”. As the exhibition notes point out, in the 1480s Botticelli’s Florentine studio was a place of thriving commerce as well as artistic ambition. A small army of assistants and apprentices churned out prestige pieces for the ruling Medici family, serviceable stuff for everyone else, as well as stock for the shop. In addition to easel paintings, frescoes and altar pieces, busy hands got to work making tapestry, marquetry, harnesses and furniture. A certain house style prevailed, but with inevitable variations according to the individual maker. Some could imitate the master’s touch perfectly, others added something of their own. Patrons and ordinary punters alike understood the deal and didn’t mind: what mattered was the feeling of buying into a prestige brand. It has become commonplace to say that if Botticelli were working today, he might be creative director of Gucci, Prada or, indeed, Dolce & Gabbana, overseeing the core collection and several diffusion lines, as well as perfume and lipstick, too.

Before we see the evidence of the final room, though, there are the disturbed middle decades of the 20th century to attend to, when Botticelli was put to work bolstering political and artistic agendas. In the 1930s Mussolini sent The Birth of Venus, in company with old masters, around the world in order to remind everyone that, while Italy might be brawny, it was civilised, too. By 1939, when this kind of bluster was wearing thin, Salvador Dalí offended everyone at the World’s Fair in New York by trying to give Venus a fish head. That same year, the gentler, more affectionate side of surrealism was in evidence when the couturier Elsa Schiaparelli borrowed Botticelli’s enchanted visions of the natural world for her “Pagan” collection. The couturier commissioned the Lesage embroidery workshop to create three‑dimensional model flowers of the kind found everywhere in Botticelli’s mythological paintings: lilies, irises, jasmine. Schiaparelli then tacked these in a tumble to the bodice of a simple, elegant black evening dress. The effect was both deeply romantic and intellectually acute.

The second room of the exhibition deals with the circumstances of Botticelli’s rehabilitation in the 19th century after years of obscurity (everyone knew Leonardo and Michelangelo, but any mention of “Sandro” was met with blank stares). Art historians date the sea change to 1867, when the London-born poet‑painter DG Rossetti bought Botticelli’s Portrait of a Lady Known as Smeralda Bandinelli for a piffling £20. The picture of a red-haired woman in a three quarters pose sitting at a window with her hand to the frame might not have attracted much attention in Christie’s auction room, but to Rossetti it lit up possibilities for his own practice. In the painting’s simplicity and sincerity, its lack of adornment or bluster, he recognised exactly those qualities of early Renaissance art that had first enchanted him and his pre-Raphaelite brothers 20 years earlier.

Now, by a process of active engagement – he even touched up Smeralda’s cap which was looking a bit battered – Rossetti set about metabolising Botticelli’s aesthetic to the point where it became his own. The evidence is there in a series of six drawings and an oil painting, all called La Donna della Finestra, in which Rossetti poses his dear friend Jane Morris in the manner of Smeralda Bandinelli.

The same year Rossetti embarked on the first of his Donna drawings, Walter Pater wrote A Fragment on Sandro Botticelli, a pioneering piece of recovery scholarship. Ruskin, too, announced himself a fan. Little by little the world – or at least the world of Victorian England’s intelligentsia – was becoming Botticellian. When Rossetti sold Smeralda to his patron Constantine Ionides in 1880, he got 300 guineas (£315) for it, an extraordinary leap that reflected the rising critical fortunes of Botticelli and made Rossetti wonder whether he shouldn’t give up painting and become a dealer instead.

Other members of Rossetti’s circle followed suit. Edward Burne-Jones bought two important works by Botticelli, and their influence abounds in all those high-waisted, spoon-faced maidens who float across the pre-Raphaelite’s canvases with something approaching the loveliness of the master. Meanwhile William Morris, whose busy multidisciplinary workshop was in many ways a replica of Botticelli’s, absorbed the early Renaissance into many of the tapestries that he produced for his eponymous company. The Orchard, from 1893, allegorises the four seasons using female figures that could easily have danced their way out of Botticelli’s Primavera: tall, elegant and standing weightlessly on a rich carpet of flowers.

The visitor who arrives at the third and final room of the exhibition expecting to see Venus and Primavera is going to be disappointed: these superstar works will never leave the Uffizi now. But, really, it hardly matters. For the curators’ point, crisply illustrated here, is that it is the variation and range of work that originally appeared under the Botticelli brand, which explain why subsequent generations of artists have found him such a thrilling provocateur.

Thus a workshop piece such as The Virgin and Child With a Goldfinch (1500-10), with its lovely cleft-chinned Madonna and preternaturally alert Christ child, is actually a copy of something else – in this case an altarpiece made by the master’s own hand 30 years earlier. Likewise, but in reverse, another workshop production, Virgin and Child With Four Angels from 1485 already looks so disconcertingly pre-Raphaelite in its style that you have to check the date to make sure that it wasn’t done by a follower of Rossetti in the 1890s. It is precisely this protean quality attached to work by “Botticelli” that has made it such a rich rummaging ground for those who come later.

How ironic, then that it was confusion, anger even, over his failure to stay the same that accounts for Botticelli’s long centuries of obscurity. You can see why in a late work such as Mystic Nativity (1501). Its lack of scale and perspective – the Virgin and Child are twice the size they should be while the ancillary figures are stiffly jointed – suggest not so much a falling off in technique as a baffling return to a medieval way of painting the world. Art historians ascribe this to the fact that, in his last decade, Botticelli came under the influence of Savonarola, the Dominican who swept into Florence just as the Medici, Botticelli’s long-time patrons, were being swept out.

Sounding a bit like Oliver Cromwell avant la lettre, Savonarola thundered against devotional art that paid too much attention to the folds in a Madonna’s silk robe, and not enough to the awfulness of a jealous God. Botticelli answered the call, willingly it seems, by producing a new, archaic kind of work designed to make Florence tremble in terror at the coming apocalypse – his Mystic Crucifixion (c1500), with its heaven-sent thunderbolts, is particularly terrifying.

Such an apparently backwards swerve doesn’t fit well into the grand historical narrative that requires art to be always moving forward, becoming more gentle, refined, human and humane in the process. Botticelli’s goose was also cooked by a nasty bit of smearing on the part of Giorgio Vasari, author of the foundational Lives of the Artists. Writing 40 years after Botticelli’s death in 1510, Vasari claimed on no good grounds that, in his last years, Botticelli became a religious fanatic who made bad art while also, confusingly, being a wasteful hedonist. It was assassination by biography and had a lasting effect on the late artist’s reputation, leaving those heroes of the high Renaissance, Leonardo and Michelangelo, way out in front.

Only when a generation of young Englishmen in the mid-19th century started to look with fresh eyes at art that seemed to embody an earlier, more authentic style of painting did Botticelli come back into focus. From that moment, as the V&A’s exhibition triumphantly demonstrates, successive generations of artists, designers and taste-makers have found that they too could repurpose Botticelli for their own ends without – and this is important and hard to explain – ever making him look trivial or banal. After all, when Duchamp went looking for an iconic image to vandalise in 1919, it was on Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, and not Sandro’s Venus, that he scribbled that moustache.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion