The small wooden shack stands desolate against a glowering sky. A lone telegraph pole, two skeletal trees and an outhouse complete a scene that could be the setting for countless country songs about growing up poor in hard times.

“It isn’t what a picture is of,” the great American photography curator John Szarkowski once said. “It is what it is about.” His words strike me while looking at Alec Soth’s image of Johnny Cash’s boyhood home.

The image befits the self-made myth of the Man in Black, and hints at the autobiographical authenticity that underpins it. Like so many Soth images, it walks the line between the romantic and the resoundingly real, as well as between documentary and fine art – a hinterland he has negotiated more sure-footedly than any other photographer of his generation.

The title for Soth’s first British retrospective is Gathered Leaves, which hints at his ability to chronicle the many – often conflicting – notions of American life that coexist in such a politically riven country, but also his prowess as a maker of photobooks. Indeed, the show is curated chronologically around his four major books: Sleeping By the Mississippi (2004), Niagara (2006), Broken Manual (2010) and Songbook (2015).

This refreshingly straightforward approach works well, although it does not entirely do justice to the variety of Soth’s work. He is, as the exhibition introduction notes, “a photojournalist, blogger, self-publisher, Instagrammer and educator” – someone who understands that today the sharing of the image often seems as crucial as the image itself. The retrospective includes vitrines devoted to editions of his books, maquettes, zines, collaborations and dispatches on Tumblr from various US cities, although it is Alec Soth the image-maker who is elevated across four large rooms of prints.

The results are beautiful, whatever their subject matter. Painstakingly composed on a large-format camera mounted on a tripod, his images can be breathtakingly stunning in their subtle range of muted colours. Despite his use of blogs and social media, Soth is essentially a traditionalist, and there are echoes of other great photographers throughout his work, most notably Joel Sternfeld, who taught him for a time. He seems to have inherited Sternfeld’s eye for American oddity.

Soth made his name with Sleeping By the Mississippi, a kind of psychological travelogue along the 2,000-mile route of the great, mythic American river. It harks back to the great American road trips undertaken by photography masters including Walker Evans, Robert Frank and Stephen Shore, but also to literature by Mark Twain, Flannery O’Connor and Eudora Welty (who was also an attentive photographer of the American south). A discarded iron bedstead wreathed in weeds could be a resting place for Huck Finn and Jim as they hug the shore in their bid to escape the injustices of the south. Likewise, a woman holding a painting of an angel might have been dreamed up by Flannery O’Connor.

Sleeping By the Mississippi showed Soth’s instinctive grasp of narrative and metaphor, each image carefully chosen to articulate – and accentuate – his sense of the US, and the south in particular, as a place haunted by ghosts and individuals who are slightly adrift from, or wilfully outside, the norm. But his vision of the Mississippi is also located in the here and now, often ominously so. A young man called Joshua might look almost angelic in his white robes, on which the words “preacher man” have been inked across the collar, but the portrait was taken in Louisiana State Penitentiary, one of the most notorious prisons in the US. Two women sitting side by side on a couch, legs interlocking, could be mother and daughter, but they both work as prostitutes in Davenport, Iowa.

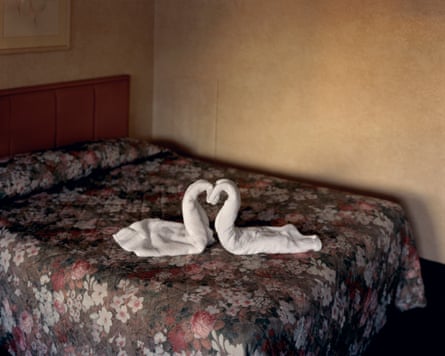

Underpinning the series, and indeed all of his work, is Soth’s restless vision and relentless curiosity. In Niagara, he finds another location steeped in contradictions, a place of “spectacular suicides and affordable honeymoons,” as he puts it. Soth’s Niagara is both mundane and majestic, its mythology invested with so much hope that disappointment and despair are an inevitable consequence. In the photobook, Richard Ford’s short meditation on the same caught its paradoxical sense of place perfectly – love amid the drab motels and soul-sapping pawn shops. But in the exhibition the images speak for themselves. Soth again evokes a state of mind as much as an actual place, with extracts from love letters and plaintive pleas by the heartbroken punctuating the portraits of newlyweds and honeymooners, some of whom seem perfectly comfortable to pose nude and almost beatifically vulnerable for his camera.

The strange atmosphere of banality and heightened intimacy is sustained throughout, further evidence of Soth’s meticulous editing and his almost writerly understanding of how to sustain a mood.

Soth’s most intriguing series to date is also the least seen: Broken Manual, which appeared in a criminally small run, before reappearing on the collector’s market for outrageous sums. Here, portraits of contemporary hermits, recluses and lone survivalists have an almost religious aura: one man resembles a latter-day Rasputin; another looks like he belongs in the Julia Margaret Cameron exhibition next door.

On one wall, a monochrome triptych of objects belonging to a recluse is loaded with suggestion: a homemade knife, two mushrooms (possibly hallucinogenic) and an object that at first glance resembles a fake dog bone, but turns out to be a male sex toy.

On another wall, a huge print of an intense, nude young man standing ankle-deep in a pool of water in an Edenic landscape speaks volumes about Soth’s powers of persuasion and his ability, particularly in portraits, to blur the line between fine art and documentary. The image is almost classical – man in his natural state in an unsullied landscape – but the intense stare and shaved head hints at the social discontent that often drives this kind of retreat from mainstream in the US.

Soth’s gaze in Broken Manual marked an interesting conceptual shift, his pictures playing with tropes of American romanticism that recall Whitman and Thoreau, and also (in his use of long-lens photography and grainy imagery) mimicking surveillance and spy-camera footage. His subjects could be benign or dangerous, back-to-nature hermits or tooled-up survivalists, but the ephemera that appears in this room makes abundantly clear what his pictures only hint at. One self-published periodical Soth found for sale online is called Improvised Weapons in American Jails by the punningly named Jack Luger. Another is called How to Build Flash/Stun Grenades. It features a dramatic cover mock-up of a man in an Aran sweater recoiling from one such weapon. (Like Jack Luger’s book, it is available on Amazon, alongside a host of other hair-raising DIY survivalist titles.)

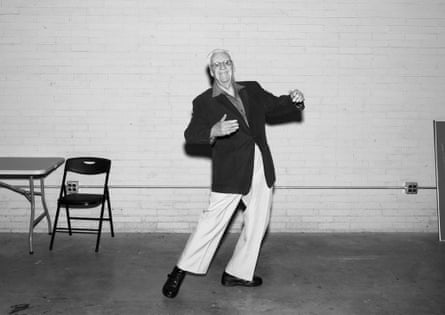

Soth’s most recent series, Songbook, also speaks of American discontent (albeit of a less violent, if more widespread, kind). Using the canonical Great American Songbook as his starting point, Soth meditates on the death of community in the US through what he calls “a musical approach to the arrangement of pictures”. It is a lyrical, almost elegiac work, photographed in black and white, and shot through with what could be mistaken for nostalgia. It is a grand continuation of another Soth series, Looking for Love, which shows how Americans attempt – and often fail – to connect with each other in a social-media driven world, where terms such as “community”, “friend” and indeed “social” only mask a lack of the same.

Whether they work best in book or print form, his Songbook images are again immaculate. My one quibble with the show is that it does not reflect Soth’s importance as “a photojournalist, blogger, self-publisher, Instagrammer and educator”, or quite impart the significance of his Little Brown Mushroom self-publishing imprint, which is the model for a new and ultra-contemporary approach – serious, but ironic and mischievous – to the making and disseminating of images. The zines and limited-run titles here only hint at the fertile imagination that underpins everything he does, from his pseudonymous publications to The Winnebago Workshop, his mobile multimedia classroom for kids.

It would take another exhibition to do justice to Alec Soth the ultra-contemporary renaissance man of photography. For now, it is Soth the traditional photographer that is on show – and this thoughtful retrospective is conclusive proof that he is the most important visual chronicler of the US at work today.

Gathered Leaves is at the Science Museum’s Media Space gallery, in London, until 28 March 2016.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion