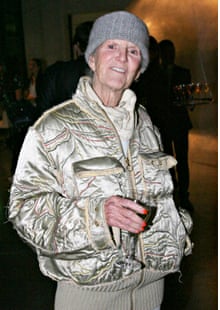

The artist Elaine Sturtevant (known simply as Sturtevant), who has died aged 89, was best known for her repetition of works by other artists, anticipating at an early date the debates surrounding notions of authenticity, authorship, originality and representation that became central to the discourse around art in the late 1960s and 70s.

She made her controversial artistic debut in 1965 at the Bianchini Gallery, New York, when she repeated Andy Warhol's Flowers, a series of silk-screen prints that he had shown a couple of weeks before. Today it is par for the course for images to be sampled, re-used and edited, but in the early 60s, acts of appropriation were yet to become a staple of the art world.

Warhol, however, found nothing to complain about in her gesture, and even showed her the techniques he used. He understood that Sturtevant was pursuing similar concerns to his own. With his famous Campbell's soup cans, which he screen-printed on canvas in his "factory", Warhol demonstrated that the lowly objects and manufacturing methods of mass culture are also worthy subjects and tools of art. In a sense, Sturtevant went even further than that: she explored and dismantled the myth of the artist, and the aura that is accorded to the original work of art.

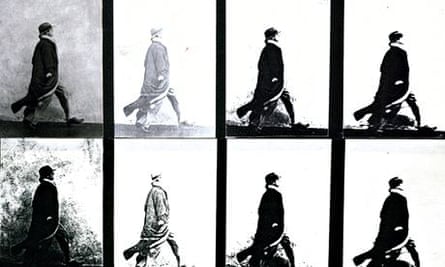

Sturtevant's works are not merely copies, since her aim was not to achieve an exact replica. Instead, she reconstructed them from memory, using the same techniques as the artists whom she imitated. (So closely did she approach Warhol's working method, that in response to repeated questions regarding his technique, he replied: "I don't know. Ask Elaine.")

Key to her thinking was the relationship between repetition and difference: the difference from the original forces one to look beyond the surface. She achieved these crucial differences through working by hand, without recourse to mechanical reproduction of any kind. As she said: "The work is done predominantly from memory, using the same techniques, making the same errors and thus coming out in the same place."

For more than five decades, Sturtevant explored what she described as "the silent power of art", probing beyond art's surface appearance to expose its underlying conceptual structure and to "trigger thinking". When she moved from the US to Paris in 1990, it was something of an escape. By this time, many European museums had devoted shows to her work, while in her own country, people reacted with irritation or misunderstanding to her approach – including some of the artists whose work she repeated.

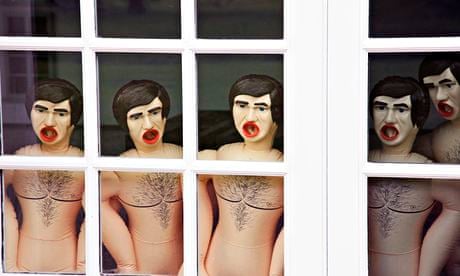

In 2000 Sturtevant began to embrace film and video, advertising and internet-based images, producing work that reflects the fragmented and pervasive nature of our image-saturated culture. As Adrian Searle wrote in the Guardian in 2013, "Sturtevant's most recent work is less about repeating other people's art, or even her own, than it is about the constant repetitiousness of experience in the post-internet age. If Sturtevant hadn't done what she did, someone else would have. Someone, somewhere, is doubtless repeating Sturtevant now. The cycle is endless."

Recently, there has been a massive resurgence of interest in her work in museums across the world, with shows at venues including the Deichtorhallen Hamburg (1992); the Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt am Main (2004); the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (2010), the Moderna Museet, Stockholm (2012); the Kunsthalle, Zurich (2012) and the Serpentine Galleries, London (2013). Her new popularity is easily explained: in the internet age there is a greater understanding of her extraordinary creativity with borrowed imagery.

Born in Lakewood, Ohio, Sturtevant attended the University of Iowa. There, she read Spinoza, along with Nietzsche, Hegel and Schopenhauer. She later re-read Spinoza in the light of the writings of Gilles Deleuze and Michel Foucault, and her great unrealised project, which we often discussed over the last months of her life, was to write a libretto for an opera about the philosopher.

In the 50s, Sturtevant moved to New York, where she received a master's degree from Columbia University. She started to exhibit her groundbreaking and enigmatic work in the mid-60s. Her idea of repeating other artists' work was not an epiphany, but grew out of a slow evolution of thinking; she spent a year drawing and clarifying her ideas before she began. At that time, abstract expressionism and pop art ruled. "The abstract expressionists were all emotion on the surface," she said, "and the pop artists were about mass culture, so this of course triggers thinking about the under-structure of art. What is the power, the silent power, of art? I started thinking about that and, after a long period of thinking, I realised this would be a way of doing it. It seems so simple, but I had to probe and reflect that it was correct. It's always the simplest ideas that are somehow the most difficult to grasp."

A landmark show was held at the Everson Museum, New York, in 1973, where she presented her remakes of Joseph Beuys' felt sculptures, and her initial foray into film-making with a remake of Warhol's Empire.

However, as Sturtevant later recalled: "The reviews for that show were the same as always – that I was reviewing history, or that the pieces were all copies, blah blah blah. I realised that if I continued to work and get that kind of critique, then the work would get diluted. So I decided to wait until the retards caught up. And, indeed, they did."

Sturtevant, like Duchamp before her – whose disenchantment with the art world led him to devote himself to chess – withdrew from exhibiting and turned to playing tennis. From the 80s onward, when appropriation became a key strategy among young artists, her work had exerted a powerful influence on new generations of artists, and recognition of her importance and impact has steadily grown over the past three decades. Her pioneering work is now recognised as having presaged the unattributed information and endlessly repeating imagery that characterise the digital world of today. As she commented on the occasion of her 2012 retrospective, Sturtevant: Image Over Image, at the Moderna Museet, Stockholm: "What is currently compelling is our pervasive cybernetic mode, which plunks copyright into mythology, makes origins a romantic notion, and pushes creativity outside the self. Remake, reuse, reassemble, recombine – that's the way to go."

In 2008 Sturtevant was awarded the Francis J Greenburger award and in 2011 received the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement at the 54th Venice Biennale. Remarkably, however, when we presented her exhibition Leaps, Jumps and Bumps at the Serpentine Gallery in 2013, it was her first show in a public institution in the UK. The exhibition represented the breadth of ideas with which she engaged in her practice, bringing together key works in a range of media, from painting to installation to video. She conceived of the exhibition as a Gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art – where her videos and installations and wallpaper and sound formed the total installation. Finite Infinite (2010), for example, is a large-scale projection of a dog running in an endless loop, conceived to echo the themes of looping, repetition and difference that were central to her work.

In September 2013, Sturtevant was awarded the Kurt Schwitters prize for lifetime achievement by the Sprengel Museum and many now regard her as one of the most important artists of the 21st century.

She is survived by her daughter, Loren Muzzey.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion