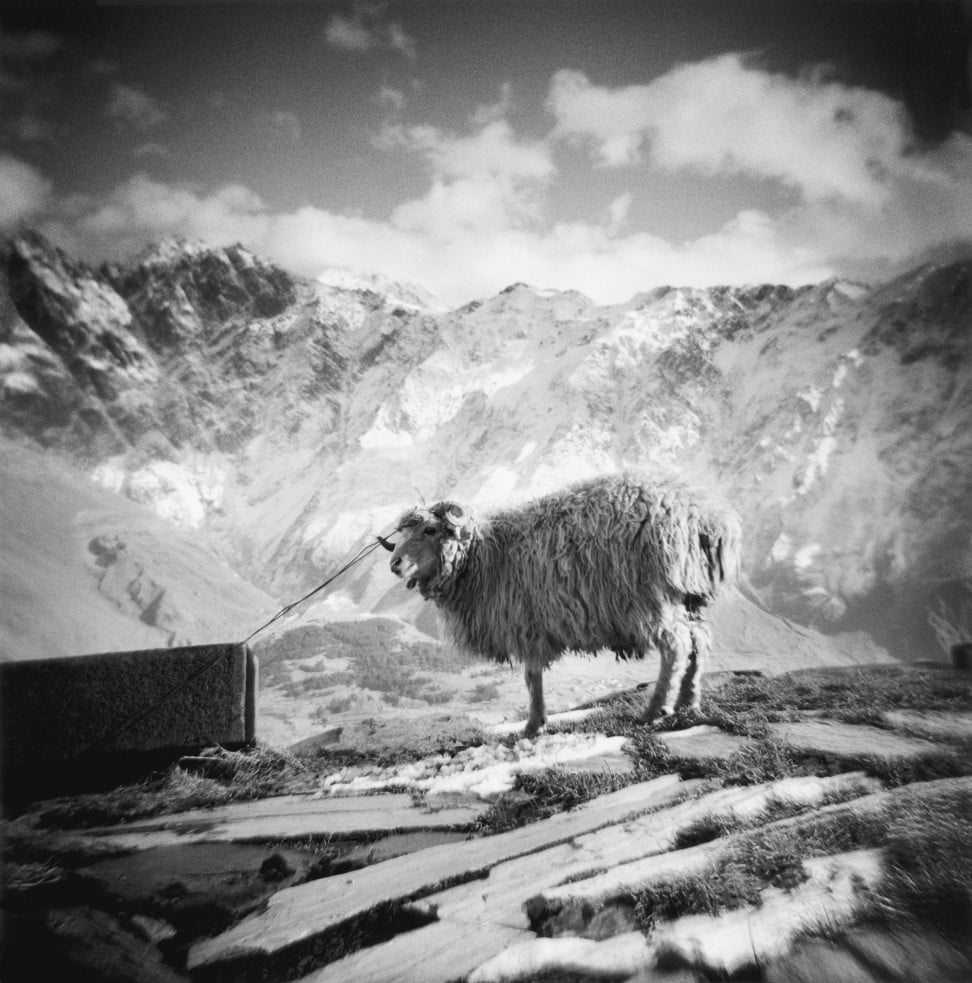

Ethereal landscapes captured on a Holga, a made-in-Hong-Kong toy camera, by Michael Kenna

The Briton, famed for his black-and-white landscapes, loves the plastic pocket camera for its unpredictability and the whimsical quality of the resulting photos

For more than 40 years, Kenna has been taking minimalistic, black-and-white photographs of everything from religious sites to empty factories and abandoned piers. Mostly, though, he’s famous for landscapes, and even in today’s digital world of smartphones and social media, he uses film cameras, often wandering alone in cities or the countryside at night.

Kenna prefers not to be in total control of his photography, allowing accidents to happen as he attempts to capture the “unseen”, which hints at the supernatural, sacred or spiritual.

“When you photograph a tree or a mountain,” he says, “there has to be some sort of exchange of energy and sense of life in what you’re photographing.”

While Kenna started using Hasselblad cameras about four decades ago, working with Holgas injected new life into his photography.

“The Hasselblads I work with are heavy, cumbersome,” he says. “They make you really think about what you’re doing. The Holga is a very whimsical, instant, unpredictable piece of equipment. You can carry it in your pocket. With anything you do for long periods of time, it becomes a bit predictable. If you can somehow throw a wrench in that and allow another influence into your creative process, it helps.”

In the first 20 years of the company, more than a million Holgas were sold.

The Holga is proof, Kenna suggests, that expensive gear isn’t vital for good photography.

“It’s like a pencil,” he says. “You can use it to do an incredible drawing or write some amazing verse, or be an accountant. It’s the same with a camera. It’s about your vision.”

Taken for fun while on assignments or during his own photography expeditions, the photos in Holga feature Buddhas and birds, trees and seascapes and more. There are pictures from France, Senegal, Egypt and elsewhere, but Asia dominates Kenna’s work, the continent having played a key role in his early career.

“My influences were strongly European,” he says. “There was a lot of darkness, a lot of shadows. When I went to Asia, particularly Japan, the equation shifted, so I was using white more, and things were becoming more abstract, more minimalistic.”

Some of Kenna’s best photos were taken in Japan, including images of torii gates on the ocean, lone trees in the snow, and swans on wintry lakes. Japan is “a country where the land is alive and powerful”, he says, and where he became interested in Buddhism and Zen.

Kenna also focused his Holgas on South Korea, India, Thailand and China, and several intriguing photos were taken in Hong Kong, which Kenna has visited many times.

I’m not really against technology. It’s just I don’t choose to really embrace it myself because I’m still so content with and challenged by traditional methods of photography

“Hong Kong’s a little difficult for me,” he says, “as it’s packed with people, it’s hot, it’s busy and it goes at a mile a minute. But I think you can always find places of quiet and contemplation. Certainly, if you get out of the main populated areas of Hong Kong, there are some very beautiful, calm and serene places.”

But can a basic camera such as the Holga capture their spirituality?

“That’s something that comes out of one’s fundamental belief system in what the world is,” Kenna says. “Whenever you have a conversation with any subject matter, some of that belief system will come through. I happen to like the idea that there is something more than this physical presence we have.”

Kenna’s reverent approach is rooted in his childhood. Born in 1953, into a large Catholic family in Lancashire, northern England, his ambition at the age of 10 was to become a priest, and he went to a Catholic boarding school. Although he’s no longer a practising Catholic, he sees a link between religion and photography.

“Perhaps because of these early influences, no matter what’s visible in front of the camera, I’m usually trying to hint at what is unseen,” he says. “The work I produce gives a feeling of the beauty, the wonder, the mystery and the spectacular gorgeousness of creation. Where creation comes from, I won’t even enter the debate. Everyone’s entitled to their own belief system. But I don’t think the two professions are markedly far apart.”

With his Holgas, Kenna has produced square photos – very Instagram – but he has little interest in social media, despite having more than half a million Facebook followers, or in digital cameras.

“I’m not really against technology,” he says. “It’s just I don’t choose to really embrace it myself because I’m still so content with and challenged by traditional methods of photography. Everyone nowadays is a photographer, because everyone has a camera on their phone. That’s just the way it is. I choose to opt out.”

Excessive processing of images is another bugbear.

“Photography’s absolute power used to be its tie with reality: what you photographed was real and existed,” Kenna says. “That has now gone. With advertising and photography, most of it leaves me cold because I know it’s been done with technological tinkering, Photoshop and after-effects. The ubiquitous nature of photography has also changed the way serious photographers work. The market has all but disappeared. Most professional photographers can’t exist any more.”

Kenna still believes, though, that a slow, patient approach to photography can bring rewards.

“It’s a bit like Garageband on the computer,” he says. “You can make music very quickly, but to really master an instrument takes years. Most people are content to just take instant photographs and put them out into the world quickly and easily. But there are always going to be some who take the time and delve deeper.”

And Kenna will be delving back into Asia again soon.

“I’m at a point in my life where I love to photograph in many of the places I’ve photographed in the past,” he says. “I use the analogy of a friendship: it’s nice to deepen and renew and reacquaint with that person, instead of constantly meeting new people.

“I find I’m returning more to China, France, Italy and Japan. I could keep going to places like those for my whole life and still be content.”

Holga, by Michael Kenna, is published by Prestel.