Abstract

Cancer testis antigens are encoded by germ line-associated genes that are present in normal germ cells of testis and ovary but not in differentiated tissues. Their expression in various human cancer types has been interpreted as ‘re-expression’ or as intratumoral progenitor cell signature. Cancer testis antigen expression patterns have not yet been studied in germ cell tumorigenesis with specific emphasis on intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified as a precursor lesion for testicular germ cell tumors. Immunohistochemistry was used to study MAGEA3, MAGEA4, MAGEC1, GAGE1 and CTAG1B expression in 325 primary testicular germ cell tumors, including 94 mixed germ cell tumors. Seminomatous and non-seminomatous components were separately arranged and evaluated on tissue microarrays. Spermatogonia in the normal testis were positive, whereas intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified was negative for all five CT antigens. Cancer testis antigen expression was only found in 3% (CTAG1B), 10% (GAGE1, MAGEA4), 33% (MAGEA3) and 40% (MAGEC1) of classic seminoma but not in non-seminomatous testicular germ cell tumors. In contrast, all spermatocytic seminomas were positive for cancer testis antigens. These data are consistent with a different cell origin in spermatocytic seminoma compared with classic seminoma and support a progression model with loss of cancer testis antigens in early tumorigenesis of testicular germ cell tumors and later re-expression in a subset of seminomas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Testicular germ cell tumors are the most common solid neoplasm among men in the third and fourth decade of life.1 They are divided into seminomas and non-seminomatous germ cell tumors with a wide spectrum of histological types, which are either undifferentiated (embryonal carcinoma) or differentiated. The differentiated non-seminomatous testicular germ cell tumors may show some degree of embryonic (teratoma) or extra embryonic pattern (yolk sac tumor, choriocarcinoma).2 Despite the broad range of histological types, they originate from one common precursor lesion known as intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified—with the exception of spermatocytic seminoma, which is not associated with intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified.3, 4 It is regularly found in testicular tissue adjacent to testicular germ cell tumors.5, 6 It is important because patients with intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified have a 50% risk of developing an invasive germ cell tumor within 5 years without treatment.2, 7 Furthermore, intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified is frequently encountered in patients with an increased risk to develop a testicular germ cell tumor, eg gonadal dysgenesis,8 a previous testicular germ cell tumor9 or cryptorchidism.10, 11 POU5F1,12 PLAP13 and KIT14 are immunohistochemical markers for the identification of intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified.

Cancer testis antigens are usually expressed in normal germ line tissues, such as placenta, ovary and testis. They are the product of germ line-associated genes in those tissues, but they can be found in various human cancers, too.15, 16, 17 More than 100 cancer testis genes have been described so far, using different methods, including Serological Analysis of Recombinant Expression libraries.17 In general, there are two types of cancer testis genes: those that are encoded on the X chromosome (cancer testis-X antigens) and those that are not (non-X cancer testis antigens).17 However, their function remains largely unknown, although cancer testis antigens are supposed to have a role in normal tissue development and tumorigenesis of various cancers. Recently, it has been shown that MAGEA cancer testis antigens inhibit the function of p53 by blocking its interaction with chromatin.18 In several cancer types, eg multiple myeloma, bladder cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, breast, colorectal and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, the high expression of cancer testis-X genes is associated with poor differentiation grade, progressive disease and worse prognosis.19, 20, 21, 22

There are only limited studies on cancer testis antigen expression in testicular germ cell tumors. MAGEA1, MAGEA2, MAGEA3 and MAGEA4 mRNA expression has been analyzed in 32 testicular germ cell tumors and was found in 68–82% of seminomas, mixed germ cell tumors with seminomatous components and some mixed non-seminomatous germ cell tumors.23 Cheville et al24 studied 43 germ cell tumors and described MAGEA1 and MAGEA3 protein expression only in 17–42% of seminomas but not in non-seminomatous tumors. In another study, MAGEC2 mRNA expression was detected in four of five seminomas by RT-PCR.25 On protein level, Aubry et al26 investigated the expression of MAGEA4 in 27 germ cell tumors (17 seminomas and 10 non-seminomas). About one-third of the seminomas were negative. Consequently, we analyzed the expression of MAGEA4, MAGEC1, GAGE1 and CTAG1B with emphasis on testicular germ cell tumor development.

Materials and methods

Patients

Three hundred and twenty-five patients with testicular germ cell tumors were retrieved from the files of the Institute of Surgical Pathology of the University Hospital Zurich, Switzerland from 1990 to 2003 and were recently reported.27 According to the 2004 WHO Classification,28 the tumors were classified by an experienced uropathologist (AB). The series included 94 mixed germ cell tumors (49 with and 45 without a seminomatous component), 4 spermatocytic seminomas, 207 classic seminomas, 19 pure embryonal carcinomas and 1 pure mature teratoma. Following components were seen in the 94 cases of mixed germ cell tumors: seminoma, embryonal carcinoma, yolk sac tumor, choriocarcinoma and teratoma.

Intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified was included from 20 patients with testicular germ cell tumors. Intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified was identified morphologically on hematoxylin and eosin-stained histological section and was confirmed by immunohistochemical stainings for KIT, POU5F1 and placental alkaline phosphatase.

The project has been approved by the local ethics committee (ref. number StV 25-2008).

Tissue Microarray

A tissue microarray was constructed as described before.27 In summary, the tissue microarray contained testicular tumor components of 254 seminomas, 89 embryonal carcinomas, 51 yolk sac tumors, 54 teratomas, 10 choriocarcinomas and 4 spermatocytic seminomas. Additionally, we included intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified and non-tumor testicular tissue from 20 tumor patients. Thereby our tissue microarray comprised 1030 tumor tissue cores. During processing, 9 cases (18 tissue cores) were lost. For the evaluation of the immunostaining, we considered 462 different histological tumor components, 20 intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified and 20 non-neoplastic testicular tissues.

Histology and Immunohistochemistry

Three-micron thick sections of tissue microarray blocks of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were mounted on glass slides (SuperFrost Plus; Menzel, Braunschweig, Germany), deparaffinized, rehydrated and stained with hematoxylin and eosin using standard histological techniques. We investigated the cancer testis antigens MAGEA3, MAGEA4, MAGEC1, GAGE1 and CTAG1B. MAGEA3 was detected using the recombinant reverse chimeric antibody 21B4rc (CT Atlantic, dilution 1:500), MAGEA4 by a rabbit monoclonal antibody (Lifespan Biosciences, dilution 1:50) and MAGEC1, GAGE1 and CTAG1B by mouse monoclonal antibodies (MAGEC1 antibody from DAKO, dilution 1:80; GAGE1 antibody from BD Biosciences, dilution 1:2000; CTAG1B antibody from ZYMED Laboratories, dilution 1:10). The immunohistochemical stainings were performed with the Ventana Benchmark automated staining system (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ) using Ventana UltraView DAB reagents. All primary antibodies were diluted in Ventana diluent. Slides were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted. An experienced surgical pathologist (PKB) evaluated all tissue microarray spots. Samples were dichotomized into positive vs negative. The threshold for positivity was defined at 5% of cells positive for the marker, as previously described.15 The expression patterns were separately analyzed for each tumor component, pre-neoplastic lesion and non-neoplastic tissue (Table 1).

To verify our results from four spermatocytic seminomas, additional cases of spermatocytic seminomas were retrieved from the Institute of Pathology Lucerne and the Institute of Pathology, Zurich (Stadtspital Triemli), Switzerland and the Institute of Pathology, Karlsruhe, Germany. Twelve cases of spermatocytic seminomas were identified and included in our study. Large sections of these tumors were stained for POU5F1, MAGEA3, MAGEA4, MAGEC1, GAGE1 and CTAG1B as described above.

Results

MAGEA3 Antigen Expression

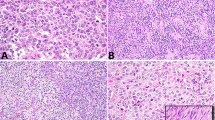

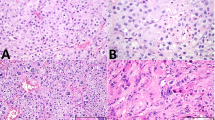

Immunohistochemical expression of MAGEA3 was only nuclear. There was a moderate-to-strong expression intensity. Stromal cells, Sertoli cells and Leydig cells were negative in all cases. In non-neoplastic germ cells, MAGEA3 displayed a nuclear expression. The staining was very strong in spermatogonia, moderate in spermatocytes and negative in spermatids and sperms. Likewise, MAGEA3 expression was lost in all cases of intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified. In seminomas, MAGEA3 was identified in 83 of 254 cases (33%) with a heterogenous moderate nuclear staining pattern, wheras all four spermatocytic seminomas showed a diffuse and strong nuclear expression, similar to that in spermatogonia. Three of 51 yolk sac tumors showed a moderate expression of MAGEA3. Choriocarcinomas, embryonal carcinomas and teratomas were all negative for MAGEA3. Syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells stained always negative (Figure 1).

MAGEA4 Antigen Expression

The immunohistochemical staining for MAGEA4 was cytoplasmic and nuclear. There was a moderate-to-strong expression intensity. Stromal cells, Sertoli cells and Leydig cells were negative in all cases. In non-neoplastic germ cells, MAGEA4 showed a consistent and very strong expression in spermatogonia, whereas spermatocytes, spermatids and sperms were negative. All cases of intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified were negative. In seminomas, MAGEA4 was identified in 26 of 254 cases (10%) with a moderate to strong cytoplasmic and nuclear expression. The spermatocytic seminomas showed a moderate-to-strong MAGEA4 immunostaining. Yolk sac tumors, choriocarcinomas, embryonal carcinomas and teratomas were all negative for MAGEA4. Syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells were always negative (Figure 1).

MAGEC1 Antigen Expression

Immunohistochemical expression of MAGEC1 was only cytoplasmic and showed a moderate to strong intensity. In stromal cells, Sertoli cells and Leydig cells, the MAGEC1 staining was negative. In non-neoplastic germ cells, MAGEC1 showed a consistent and strong cytoplasmic expression in spermatogonia and decreased in spermatocytes, spermatids and sperms, which showed a moderate staining. In intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified, the expression of MAGEC1 was reduced or totally lost compared with non-neoplastic testicular tissue. In seminomas, MAGEC1 was identified in 102 of 254 cases (40%) with a heterogenous staining pattern and weak-to-moderate staining intensity. All spermatocytic seminomas showed a diffuse moderate-to-strong MAGEC1 immunostaining, similar to that in normal germ cells. Yolk sac tumors, choriocarcinomas, embryonal carcinomas and teratomas were all negative for MAGEC1. Syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells stained always negative (Figure 1).

GAGE1 Antigen Expression

GAGE1 showed a mainly nuclear expression with a strong intensity. Stromal cells, Sertoli cells and Leydig cells were negative. In non-neoplastic germ cells, GAGE1 displayed a consistent and strong nuclear and cytoplasmic expression in non-neoplastic testicular tissue. The staining was very strong in spermatogonia and spermatocytes and strong-to-moderate in spermatids and sperms. GAGE1 expression was lost in all cases (100%) of intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified. In seminomas, GAGE1 was identified in 25 of 254 cases (10%). All four spermatocytic seminomas showed a diffuse strong GAGE1 immunostaining but with a cytoplasmic pattern in contrast to the nuclear expression in spermatogonia. Yolk sac tumors, choriocarcinomas, embryonal carcinomas, teratomas and syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells were negative (Figure 1).

CTAG1B Antigen Expression

Immunohistochemical expression of CTAG1B was cytoplasmic and showed a moderate to weak signal. Stromal cells, Sertoli cells and Leydig cells were negative. In non-neoplastic germ cells, CTAG1B displayed a sometimes heterogenous cytoplasmic expression. The staining was moderate in spermatogonia and spermatocytes and negative in spermatids and sperms. CTAG1B was not expressed in intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified. In seminomas, CTAG1B was identified in 8 of 254 cases (3%). All four spermatocytic seminomas showed a moderate CTAG1B immunostaining. Yolk sac tumors, choriocarcinomas, embryonal carcinomas, teratomas and syncytiotrophoblastic giant cells were negative for CTAG1B (Figure 1).

Cancer Testis Antigen and POU5F1 Expression in Additional Cases of Spermatocytic Seminomas

Large sections of 12 spermatocytic seminomas were stained for POU5F1, MAGEA3, MAGEA4, MAGEC1, GAGE1 and CTAG1B. The results confirmed the findings of the tissue microarray analysis: All spermatocytic seminomas showed a predominantly strong expression of cancer testis antigens with the exception of CTAG1B, which showed a weak-to-moderate staining. All spermatocytic seminomas were negative for POU5F1 (Table 2).

Discussion

We report on cancer testis antigen expression patterns in testicular germ cell tumors and their precursor lesion intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified. MAGEA3, MAGEA4, MAGEC1, GAGE1 and CTAG1B are absent in all intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified, whereas 4–40% of classic seminomas and all spermatocytic seminomas were positive. The tissue microarray approach may underestimate the real prevalence, because cancer testis antigen expression is characterized by intratumoral heterogeneity.29 According to the current hypothesis that classic seminomas originate from intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified, our results suggest re-expression of cancer testis antigens in classic seminomas.

Expression of cancer testis antigens is restricted to germ cells in the normal testis.30 Cancer testis antigens are usually highly expressed during the early phases of spermatogenesis, especially in spermatogonia and primary spermatocytes, but not in spermatids.17 Therefore, it seems likely that cancer testis antigens repress the expression of genes, which are necessary for cell differentiation.

On the other hand, our findings indicate that the early loss of cancer testis antigen expression in intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified might be associated with malignant transformation and tumor progression in germ cell tumorigenesis concerning almost all non-seminomatous germ cell tumors and more than half of classic seminomas. Interestingly, a subset of classic seminomas was positive for cancer testis antigens. It is known that cancer testis antigens can also be re-expressed in malignant tumors, whereas the expression of cancer testis antigens varies in different tumor types and is associated with higher grade and advanced stage tumors, eg in prostate cancer,31 melanoma32 or hepatocellular carcinoma.19

The functional and mechanistic implications of cancer testis antigen re-expression in some seminomas are unclear. Previous studies indicate that MAGEA1 can act as transcriptional repressor of genes required for differentiation.33 MAGE genes encode multifunctional regulator molecules that exert a range of effects. Transfection of cells with MAGEA2 or MAGEA6 genes confers a proliferative advantage and could make an important contribution to tumorigenesis.34

In contrast to the early loss of cancer testis antigens in tumorigenesis of seminomatous and non-seminomatous germ cell tumors, all spermatocytic seminomas showed a strong expression of cancer testis antigens. Therefore, our data support the common hypothesis of a different cell origin concerning spermatocytic seminoma and classic seminoma.1, 35 Although intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified is considered to be derived from developmentally arrested gonocytes,2, 36, 37, 38 there is some controversy about the progenitor cell in spermatocytic seminoma.39 Previous studies suspected primary spermatocytes40 or spermatogonia35, 41 as progenitor cells. In our study, we found a strong expression of cancer testis antigens in spermatogonia and in spermatocytic seminoma, which is consistent with an origin of spermatocytic seminoma from spermatogonia, too.

Spermatocytic seminoma is an uncommon testicular germ cell tumor accounting for only 1–2% of all testicular tumors and also occurs in older men.42 It is important to distinguish spermatocytic seminoma from classic seminoma, because spermatocytic seminoma almost never metastasizes (except if there is a sarcomatous component).43, 44 Patients usually do not benefit from an adjuvant therapy after orchiectomy. Typically, there is no intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified neighboring spermatocytic seminoma.39 Spermatocytic seminomas are largely negative for most immunohistochemical germ cell tumor markers, including PLAP, TNFRSF8 (CD30), POU5F1, SOX2, SOX17 and many others. Expression of KIT depends on the antibody used.27, 45 Rajpert-De Meyts et al35 already demonstrated that spermatocytic seminoma expresses the cancer testis antigen MAGEA4.

We have previously analyzed MAGEC2 protein expression in testicular germ cell tumors and in hepatocellular carcinoma19 as well as in prostate cancer31 and malignant melanoma.32 MAGEC2 has a different expression pattern compared with other cancer testis antigens used in this study. MAGEC2 protein showed exclusively a nuclear expression pattern with frequent expression in seminomas, spermatocytic seminomas and intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified. It was also absent in embryonal carcinoma. This is consistent with the observation by Zhuang et al,46 who have shown that MAGEC2 protein expression is restricted to the nucleus and not to the cytoplasm. In contrast, MAGEC1 protein expression was found only in the cytoplasm. It was lost in intratubular germ cell neoplasia unclassified and only 40% of classic seminoma were positive for MAGEC1. This different expression pattern is interesting, because these two cancer testis antigens show a very similar sequence at the C-terminal region, which contains the MAGE homologous sequence.32, 47 Immunohistochemical studies have shown MAGEA1 protein expression in the nucleus and cytoplasm of spermatogonia and primary spermatocytes.30 Also, GAGE1 and CTAG1B immunoreactivity is both nuclear and cytoplasmic, whereas MAGEC1 immunoreactivity is only cytoplasmic without nuclear expression.20, 48

In conclusion, we found an early loss of cancer testis antigen expression (MAGEA3, MAGEA4, MAGEC1, GAGE1 and CTAG1B) in intratubular germ cell neoplasia and a re-expression in a subset of classic seminomas in contrast to spermatocytic seminomas, which were strongly positive for the cancer testis antigens mentioned above. We provide evidence that there are different phenotypic patterns of tumorigenesis in classic and spermatocytic seminomas.

References

Gilbert D, Rapley E, Shipley J . Testicular germ cell tumours: predisposition genes and the male germ cell niche. Nat Rev Cancer 2011;11:278–288.

Oosterhuis JW, Looijenga LH . Testicular germ-cell tumours in a broader perspective. Nat Rev Cancer 2005;5:210–222.

Skakkebaek NE . Possible carcinoma-in-situ of the testis. Lancet 1972;2:516–517.

Jones TD, Ulbright TM, Eble JN et al. OCT4: A sensitive and specific biomarker for intratubular germ cell neoplasia of the testis. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:8544–8547.

Coffin CM, Ewing S, Dehner LP . Frequency of intratubular germ cell neoplasia with invasive testicular germ cell tumors. Histologic and immunocytochemical features. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1985;109:555–559.

Jacobsen GK, Henriksen OB, von der Maase H . Carcinoma in situ of testicular tissue adjacent to malignant germ-cell tumors: a study of 105 cases. Cancer 1981;47:2660–2662.

Giwercman A, von der Maase H, Skakkebaek NE . Epidemiological and clinical aspects of carcinoma in situ of the testis. Eur Urol 1993;23:104–110 discussion 11-4.

Muller J, Skakkebaek NE, Ritzen M et al. Carcinoma in situ of the testis in children with 45,X/46,XY gonadal dysgenesis. J Pediatr 1985;106:431–436.

von der Maase H, Rorth M, Walbom-Jorgensen S et al. Carcinoma in situ of contralateral testis in patients with testicular germ cell cancer: study of 27 cases in 500 patients. BMJ 1986;293:1398–1401.

Krabbe S, Skakkebaek NE, Berthelsen JG et al. High incidence of undetected neoplasia in maldescended testes. Lancet 1979;1:999–1000.

Giwercman A, Bruun E, Frimodt-Moller C et al. Prevalence of carcinoma in situ and other histopathological abnormalities in testes of men with a history of cryptorchidism. J Urol 1989;142:998–1001 discussion 2.

de Jong J, Stoop H, Dohle GR et al. Diagnostic value of OCT3/4 for pre-invasive and invasive testicular germ cell tumours. J Pathol 2005;206:242–249.

Giwercman A, Cantell L, Marks A . Placental-like alkaline phosphatase as a marker of carcinoma-in-situ of the testis. Comparison with monoclonal antibodies M2A and 43-9F. APMIS 1991;99:586–594.

Rajpert-De Meyts E, Skakkebaek NE . Expression of the c-kit protein product in carcinoma-in-situ and invasive testicular germ cell tumours. Int J Androl 1994;17:85–92.

Jungbluth AA, Silva WA Jr., Iversen K et al. Expression of cancer-testis (CT) antigens in placenta. Cancer Immun 2007;7:15.

Yuasa T, Okamoto K, Kawakami T et al. Expression patterns of cancer testis antigens in testicular germ cell tumors and adjacent testicular tissue. J Urol 2001;165:1790–1794.

Simpson AJ, Caballero OL, Jungbluth A et al. Cancer/testis antigens, gametogenesis and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2005;5:615–625.

Marcar L, Maclaine NJ, Hupp TR et al. Mage-A cancer/testis antigens inhibit p53 function by blocking its interaction with chromatin. Cancer Res 2010;70:10362–10370.

Riener MO, Wild PJ, Soll C et al. Frequent expression of the novel cancer testis antigen MAGE-C2/CT-10 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer 2009;124:352–357.

Theurillat JP, Ingold F, Frei C et al. NY-ESO-1 protein expression in primary breast carcinoma and metastases: correlation with CD8+ T-cell and CD79a+ plasmacytic/B-cell infiltration. Int J Cancer 2007;120:2411–2417.

Scanlan MJ, Gure AO, Jungbluth AA et al. Cancer/testis antigens: an expanding family of targets for cancer immunotherapy. Immunol Rev 2002;188:22–32.

Bergeron A, Picard V, LaRue H et al. High frequency of MAGE-A4 and MAGE-A9 expression in high-risk bladder cancer. Int J Cancer 2009;125:1365–1371.

Hara I, Hara S, Miyake H et al. Expression of MAGE genes in testicular germ cell tumors. Urology 1999;53:843–847.

Cheville JC, Roche PC . MAGE-1 and MAGE-3 tumor rejection antigens in human germ cell tumors. Mod Pathol 1999;12:974–978.

Lucas S, De Plaen E, Boon T . MAGE-B5, MAGE-B6, MAGE-C2, and MAGE-C3: four new members of the MAGE family with tumor-specific expression. Int J Cancer 2000;87:55–60.

Aubry F, Satie AP, Rioux-Leclercq N et al. MAGE-A4, a germ cell specific marker, is expressed differentially in testicular tumors. Cancer 2001;92:2778–2785.

Bode PK, Barghorn A, Fritzsche FR et al. MAGEC2 is a sensitive and novel marker for seminoma: a tissue microarray analysis of 325 testicular germ cell tumors. Mod Pathol 2011;24:829–835.

Woodward PJ, Heidenreich A, Looijenga LHJ et al. Germ cell tumours In: Eble JN, Sauter G, Epstein JE, Sesterhenn IA, (eds). World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2004, pp 221–249.

Jungbluth AA, Stockert E, Chen YT et al. Monoclonal antibody MA454 reveals a heterogeneous expression pattern of MAGE-1 antigen in formalin-fixed paraffin embedded lung tumours. Br J Cancer 2000;83:493–497.

Takahashi K, Shichijo S, Noguchi M et al. Identification of MAGE-1 and MAGE-4 proteins in spermatogonia and primary spermatocytes of testis. Cancer Res 1995;55:3478–3482.

von Boehmer L, Keller L, Mortezavi A et al. MAGE-C2/CT10 protein expression is an independent predictor of recurrence in prostate cancer. PLoS One 2011;6:e21366.

Curioni-Fontecedro A, Nuber N, Mihic-Probst D et al. Expression of MAGE-C1/CT7 and MAGE-C2/CT10 predicts lymph node metastasis in melanoma patients. PLoS One 2011;6:e21418.

Laduron S, Deplus R, Zhou S et al. MAGE-A1 interacts with adaptor SKIP and the deacetylase HDAC1 to repress transcription. Nucleic Acids Res 2004;32:4340–4350.

Peche LY, Scolz M, Ladelfa MF et al. MageA2 restrains cellular senescence by targeting the function of PMLIV/p53 axis at the PML-NBs. Cell Death Differ 2012;19:926–936.

Rajpert-De Meyts E, Jacobsen GK, Bartkova J et al. The immunohistochemical expression pattern of Chk2, p53, p19INK4d, MAGE-A4 and other selected antigens provides new evidence for the premeiotic origin of spermatocytic seminoma. Histopathology 2003;42:217–226.

Rajpert-de Meyts E, Hoei-Hansen CE . From gonocytes to testicular cancer: the role of impaired gonadal development. Ann NY Acad Sci 2007;1120:168–180.

Skakkebaek NE, Berthelsen JG, Giwercman A et al. Carcinoma-in-situ of the testis: possible origin from gonocytes and precursor of all types of germ cell tumours except spermatocytoma. Int J Androl 1987;10:19–28.

Sonne SB, Almstrup K, Dalgaard M et al. Analysis of gene expression profiles of microdissected cell populations indicates that testicular carcinoma in situ is an arrested gonocyte. Cancer Res 2009;69:5241–5250.

Eble JN . Spermatocytic seminoma. Hum Pathol 1994;25:1035–1042.

Looijenga LH, Hersmus R, Gillis AJ et al. Genomic and expression profiling of human spermatocytic seminomas: primary spermatocyte as tumorigenic precursor and DMRT1 as candidate chromosome 9 gene. Cancer Res 2006;66:290–302.

Lim J, Goriely A, Turner GD et al. OCT2, SSX and SAGE1 reveal the phenotypic heterogeneity of spermatocytic seminoma reflecting distinct subpopulations of spermatogonia. J Pathol 2011;224:473–483.

Talerman A . Spermatocytic seminoma: clinicopathological study of 22 cases. Cancer 1980;45:2169–2176.

Matoska J, Ondrus D, Hornak M . Metastatic spermatocytic seminoma. A case report with light microscopic, ultrastructural, and immunohistochemical findings. Cancer 1988;62:1197–1201.

Steiner H, Gozzi C, Verdorfer I et al. Metastatic spermatocytic seminoma—an extremely rare disease. Eur Urol 2006;49:183–186.

Decaussin M, Borda A, Bouvier R et al. Spermatocytic seminoma. A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 7 cases. Ann Pathol 2004;24:161–166.

Zhuang R, Zhu Y, Fang L et al. Generation of monoclonal antibodies to cancer/testis (CT) antigen CT10/MAGE-C2. Cancer Immun 2006;6:7.

Gure AO, Stockert E, Arden KC et al. CT10: a new cancer-testis (CT) antigen homologous to CT7 and the MAGE family, identified by representational-difference analysis. Int J Cancer 2000;85:726–732.

Tinguely M, Jenni B, Knights A et al. MAGE-C1/CT-7 expression in plasma cell myeloma: sub-cellular localization impacts on clinical outcome. Cancer Sci 2008;99:720–725.

Acknowledgements

We thank M Storz and A Wethmar (Pathology Zurich) for excellent technical assistance and Dr Alexander Schipf, Institute of Pathology Lucerne for the contribution of two additional cases of spermatocytic seminomas. This work was supported by the Zurich Cancer League (Zurich) and the Cancer Research Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bode, P., Thielken, A., Brandt, S. et al. Cancer testis antigen expression in testicular germ cell tumorigenesis. Mod Pathol 27, 899–905 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.183

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2013.183

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Cancer testis antigen expression in testicular germ cell tumors and in intratubular germ cell neoplasia

Modern Pathology (2015)

-

Seminome des Hodens

Der Pathologe (2014)