Marcel Duchamp: Fountain

Francis M. Naumann

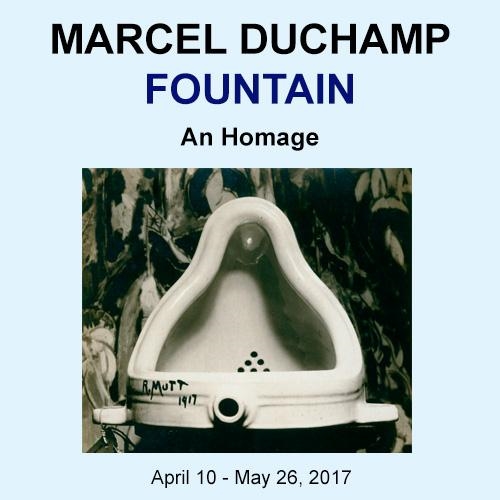

57th Street | New York | USA“Marcel Duchamp Fountain: An Homage” opens at Francis M. Naumann Fine Art on Monday, April 10, 2017, marking the 100th anniversary (to the day) of the opening of the First Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York City. In accordance with the rules of the organization—which was to have no prizes and no jury—all works that were submitted to the exhibition would be displayed, but a glistening white porcelain urinal submitted by a man identified only as Richard Mutt was unceremoniously excluded from the show, the hanging committee having objected to its status as a work of art. Eventually it would be disclosed that R. Mutt was a pseudonym concocted by Marcel Duchamp, whose submission of this work resulted in changing the very definition of art, an explosive disruption in the philosophy of aesthetics that continues to reverberate within the contemporary art world to this day.

The present exhibition celebrates the momentous implications of that gesture in the work of thirty-one artists, all of whom consciously pay homage to the precedent of Duchamp’s infamous Fountain (as the urinal was titled). Each artist approaches the work in very different ways, in most cases, reflecting their own prior aesthetic preoccupations. Only one—Elaine Sturtevant—has made what could be considered a straightforward appropriation, selecting a manufactured urinal and signing it “R. Mutt / 1917.” Even those who elected to use the form of a urinal as a point of departure have introduced significant variations, as in the case of Sherrie Levine who cast a found urinal in bronze; Douglas Vogel who purchased one manufactured in Russia and created a name tag in Cyrillic; Pablo Echaurren, who covered its surface with decorative grotesques that evoke his South American ancestry; or Richard Pettibone, who rendered multiple images of the photograph taken by Alfred Stieglitz that was reproduced the urinal in The Blind Man, inspired by the fact that he had himself experienced problems with vision.

Variations on this theme are as different as the work of the individual artists themselves. The French conceptual artist Saâdane Afif has systematically excised reproductions of Duchamp’s Fountain from books and magazines, amassing an archive of nearly 1000 separate framed pages (four of which are included in the exhibition); the California artist Ray Beldner has sewn dollar bills into the shape of a urinal that he amusingly calls Peelavie; Kathleen Gilje, a former restorer of Old Master paintings, has placed the image of a haloed urinal within the simulation of a gilded, Trecento Italian frame; the German artist Rudolf Herz has rendered multiple impressions of the urinal in anamorphic projection; Pamela Joseph, who made an entire series of paintings based on images censored in books published in Iran, has replicated the image of a pixilated urinal; Carlo Maria Mariani, an Italian-born artist known for his fusion of complex conceptual themes with neo-classical imagery, has painted a masked nude kneeling next to Duchamp’s urinal; Alexander Kosolopov, a Russian artist who now lives and works in New York has replicated Suprematist compositions inside three actual men’s urinals; the Chinese dissident Ai Weiwei has taken a photograph of Lego blocks being flushed down a toilet because the company producing the toy refused his request for a massive order on grounds that their product could not be used for political purposes (which, of course, Ai Weiwei’s work turns into a statement about censorship); the Conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth has made a work specially for this exhibition, in which neon letters replicate Duchamp’s handwriting and a framed text presents a quote from Duchamp about the readymade, one that relates indirectly to Kosuth’s own work.

Several artists have seized upon the humor implicit to Duchamp’s original gesture, as in Sophie Matisse’s creation of an edible, urinal cake (meringue covered with white frosting); Tom Shannon, who silkscreened white silk ties with the black circles echoing the pattern of drain holes in Duchamp’s urinal; Peter Saul who painted five urinals descending a staircase; Stefan Banz who arranged for the word “fountain” to be engraved on the surface of a Viagra pill. Others have found ways to allude to the mysterious disappearance of Fountain, like Caroline Bachmann who paints only the area around Fountain leavings its shape and the stand below completely blank; Saul Melman who built a large, 24-foot-high model of the urinal in wood covered by Tyvek, only to set it afire and destroy it; Mike Bidlo, who handmade a urinal in porcelain, smashed it, reassembled the pieces and had them cast into bronze; Don Joint, who created an image that elicits a verbal/visual pun on the word “urinal;” or Larry Kagan, who lights twisted pieces of steel in such a way that their shadow creates an almost magical rendition of Duchamp’s urinal (which is visible only when the light is turned on, but which, of course, instantaneously disappears when it is shut off).

No matter what accounts for the disappearance of the urinal, the very fact that an object of this importance and magnitude—one that contributed to changing the very definition of art—no longer exists today is an integral component of its mystique and allure. Just as with celebrities and world leaders who die before their time, we can only wonder what would have happened if the original artifact had survived. Would it be enshrined in a museum with visitors crowding in to see it, like tourists in the Louvre crowding before the Mona Lisa? Unlikely. It is not necessary to stand in front of a readymade to understand its meaning and importance; replicas, examples in edition and, for that matter, even reproductions can serve to stir the mind as intensely as the debate that occurred at the opening of the First Independents. What assures the historical longevity of Fountain is not the object itself, but those who think about its implications today, first and foremost artists who work in diverse styles and media, yet continue to be inspired by Duchamp and the ideas his work introduced 100 years ago.

“Marcel Duchamp Fountain: An Homage” opens at Francis M. Naumann Fine Art on Monday, April 10, 2017, marking the 100th anniversary (to the day) of the opening of the First Exhibition of the Society of Independent Artists in New York City. In accordance with the rules of the organization—which was to have no prizes and no jury—all works that were submitted to the exhibition would be displayed, but a glistening white porcelain urinal submitted by a man identified only as Richard Mutt was unceremoniously excluded from the show, the hanging committee having objected to its status as a work of art. Eventually it would be disclosed that R. Mutt was a pseudonym concocted by Marcel Duchamp, whose submission of this work resulted in changing the very definition of art, an explosive disruption in the philosophy of aesthetics that continues to reverberate within the contemporary art world to this day.

The present exhibition celebrates the momentous implications of that gesture in the work of thirty-one artists, all of whom consciously pay homage to the precedent of Duchamp’s infamous Fountain (as the urinal was titled). Each artist approaches the work in very different ways, in most cases, reflecting their own prior aesthetic preoccupations. Only one—Elaine Sturtevant—has made what could be considered a straightforward appropriation, selecting a manufactured urinal and signing it “R. Mutt / 1917.” Even those who elected to use the form of a urinal as a point of departure have introduced significant variations, as in the case of Sherrie Levine who cast a found urinal in bronze; Douglas Vogel who purchased one manufactured in Russia and created a name tag in Cyrillic; Pablo Echaurren, who covered its surface with decorative grotesques that evoke his South American ancestry; or Richard Pettibone, who rendered multiple images of the photograph taken by Alfred Stieglitz that was reproduced the urinal in The Blind Man, inspired by the fact that he had himself experienced problems with vision.

Variations on this theme are as different as the work of the individual artists themselves. The French conceptual artist Saâdane Afif has systematically excised reproductions of Duchamp’s Fountain from books and magazines, amassing an archive of nearly 1000 separate framed pages (four of which are included in the exhibition); the California artist Ray Beldner has sewn dollar bills into the shape of a urinal that he amusingly calls Peelavie; Kathleen Gilje, a former restorer of Old Master paintings, has placed the image of a haloed urinal within the simulation of a gilded, Trecento Italian frame; the German artist Rudolf Herz has rendered multiple impressions of the urinal in anamorphic projection; Pamela Joseph, who made an entire series of paintings based on images censored in books published in Iran, has replicated the image of a pixilated urinal; Carlo Maria Mariani, an Italian-born artist known for his fusion of complex conceptual themes with neo-classical imagery, has painted a masked nude kneeling next to Duchamp’s urinal; Alexander Kosolopov, a Russian artist who now lives and works in New York has replicated Suprematist compositions inside three actual men’s urinals; the Chinese dissident Ai Weiwei has taken a photograph of Lego blocks being flushed down a toilet because the company producing the toy refused his request for a massive order on grounds that their product could not be used for political purposes (which, of course, Ai Weiwei’s work turns into a statement about censorship); the Conceptual artist Joseph Kosuth has made a work specially for this exhibition, in which neon letters replicate Duchamp’s handwriting and a framed text presents a quote from Duchamp about the readymade, one that relates indirectly to Kosuth’s own work.

Several artists have seized upon the humor implicit to Duchamp’s original gesture, as in Sophie Matisse’s creation of an edible, urinal cake (meringue covered with white frosting); Tom Shannon, who silkscreened white silk ties with the black circles echoing the pattern of drain holes in Duchamp’s urinal; Peter Saul who painted five urinals descending a staircase; Stefan Banz who arranged for the word “fountain” to be engraved on the surface of a Viagra pill. Others have found ways to allude to the mysterious disappearance of Fountain, like Caroline Bachmann who paints only the area around Fountain leavings its shape and the stand below completely blank; Saul Melman who built a large, 24-foot-high model of the urinal in wood covered by Tyvek, only to set it afire and destroy it; Mike Bidlo, who handmade a urinal in porcelain, smashed it, reassembled the pieces and had them cast into bronze; Don Joint, who created an image that elicits a verbal/visual pun on the word “urinal;” or Larry Kagan, who lights twisted pieces of steel in such a way that their shadow creates an almost magical rendition of Duchamp’s urinal (which is visible only when the light is turned on, but which, of course, instantaneously disappears when it is shut off).

No matter what accounts for the disappearance of the urinal, the very fact that an object of this importance and magnitude—one that contributed to changing the very definition of art—no longer exists today is an integral component of its mystique and allure. Just as with celebrities and world leaders who die before their time, we can only wonder what would have happened if the original artifact had survived. Would it be enshrined in a museum with visitors crowding in to see it, like tourists in the Louvre crowding before the Mona Lisa? Unlikely. It is not necessary to stand in front of a readymade to understand its meaning and importance; replicas, examples in edition and, for that matter, even reproductions can serve to stir the mind as intensely as the debate that occurred at the opening of the First Independents. What assures the historical longevity of Fountain is not the object itself, but those who think about its implications today, first and foremost artists who work in diverse styles and media, yet continue to be inspired by Duchamp and the ideas his work introduced 100 years ago.

Artists on show

- Ai Weiwei

- Aldwyth

- Alexander Kosolapov

- Carlo Maria Mariani

- Caroline Bachmann

- Don Joint

- Douglas Vogel

- Ecke Bonk

- John Baldessari

- Jonathan Santlofer

- Joseph Kosuth

- Kathleen Gilje

- Larry Kagan

- Marcel Duchamp

- Marcel Dzama

- Mike Bidlo

- Pablo Echaurren

- Pamela Joseph

- Peter Saul

- Ray Beldner

- Richard Pettibone

- Rudolf Herz

- Saâdane Afif

- Saul Melman

- Sherrie Levine

- Sophie Matisse

- Stefan Banz

- Tetsuya Yamada

- Tom Hackney

- Tom Shannon

Contact details