The Alexander Calder you have (likely) never heard of

The American artist, best known for his abstract mobiles, was also a prolific portraitist who created figures from the worlds of entertainment, sports and art, including Jimmy Durante and Babe Ruth, as well as colleagues Fernand Léger and Saul Steinberg, to name a few. We spoke with the curator of the first such exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, who describes this largely overlooked aspect of the artist's career.

MutualArt

Mar 30, 2011

Best known for his abstract mobiles and stabiles, Alexander Calder (1898-1976) was also a prolific portraitist. The American artist’s work in this genre is largely overlooked and a new exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington seeks to place it in the spotlight.

The exhibition, the first to focus solely on Calder’s work in this genre, showcases portraits from the worlds of entertainment, sports and art, including Josephine Baker, Jimmy Durante, Babe Ruth, Fernand Léger and Charles Lindbergh. Most of Calder’s portraits are three-dimensional, using the unorthodox medium of wire, which he shaped into figure-like objects of considerable character and nuance.

In an interview with MutualArt, exhibition curator Barbara Zabel discusses how Calder participated in the widespread fascination with popular culture while directing his portraiture toward more meaningful relationships.

Where did the idea for this show come from? How is it organized?

In an earlier book, Assembling Art: The Machine and the American Avant-Garde, I discussed several portraits by Alexander Calder. At the time, I was struck by the fact that his portraits had received so little scholarly attention and also by the artist's prolific output in this genre. After that book was published in 2004, I embarked on further study of Calder’s portraits, and this exhibition and its accompanying book are the results. This exhibition—opening 35 years after the death of the artist—is the very first to focus solely on his work in this genre.

Calder’s portraits fall into several distinct categories—self-portraiture, the stage, sports, and the art world. And these categories determine the organization of the exhibition—and provide a conceptual framework for examining the artist’s portraits.

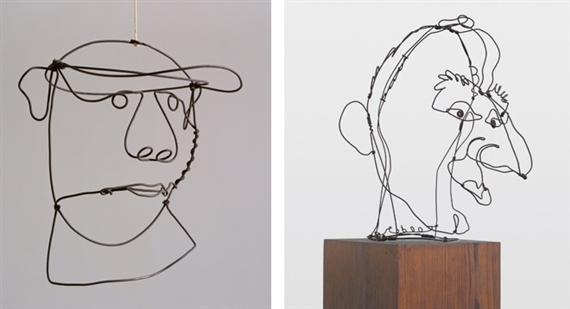

Left: George Herman “Babe” Ruth, Galvanized iron wire, c. 1936, 23.2 x 22.5 x 19.4 cm, © 2010 Calder Foundation New York / ARS, New York, Photograph © Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, NY

Right: Jimmy Durante, Wire, 1928, 30.5 x 24.1 x 29.2 cm, The Lipman Family Foundation, © 2010 Calder Foundation New York / ARS, New York

The works include painting and drawing, but mainly wire sculptures. Can you talk specifically about these? How were they created? Why are they so unique?

It was after Calder arrived in Paris in 1926 that he began bending, looping, and spiraling wire; he took a roll of industrial wire and shaped it into remarkably vivid portraits. This mode of “drawing in space” was revolutionary. At a time when most portrait sculptors were still working with mass—shaping clay, casting bronze, or carving wood or stone—Calder created wire portraits which have no mass, no firm boundaries.

By introducing transparency and shadows—for instance in his wire Self Portrait of 1968—Calder achieves a greater sense of changing perspectives and ever-shifting outlines over time. We can see into and through these portraits; their wire outlines and shadows suggesting facial expressions very much in flux and the fluidity of identity itself.

Why do you think Calder did not produce more portraits both in painting and in sculpture?

His primary artistic production increasingly involved large public and private commissions for stabiles and mobiles, which consumed great amount of time in their planning and execution; however, Calder never turned his back on the more intimate human interchange involved in portraiture, and continued to do portraits of family, friends, and colleagues throughout his career.

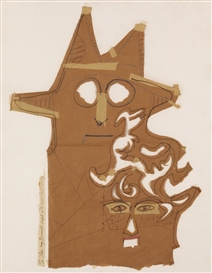

Left: Jean-Paul Sartre, Ink on paper, 1947, Sheet: 20.3 x 14.9 cm, Calder Foundation, New York, © 2010 Calder Foundation New York / ARS, New York, Photo © Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, NY

Right: Self Portrait, Ink on paper, 1957, 36.8 x 31.8 cm, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; the Ruth Bowman and Harry Kahn 20th Century American Self Portrait Collection, © 2010 Calder Foundation New York / ARS, New York

How were the works created? What were the sources of the works? Are they life studies, photograph-based?

Many of the subjects of Calder’s portraits posed for the artist, including the stage actress Katharine Cornell, composer Edgar Varèse, and artist Fernand Léger. However, other portraits were inspired by the celebrity status of the subjects, and for these Calder was inspired by publicity photographs and media posters of stars and sports icons such as Josephine Baker and Babe Ruth.

Who are the subjects of his portraits? What do his choices of subjects reveal about American culture at the time?

Most of the wire portraits were created in the 1920s, a decade when Americans became fascinated with sports icons and stage and film stars—and with celebrity itself, this at the time of a major sports craze and a dramatic surge in the production of mass media. Calder’s portraits of figures like Jimmy Durante and Babe Ruth are more about this aspect of American culture than they are about personal connection and knowledge of the subject.

Helen Wills Moody

Steel wire and wood, 1928

52.7 x 73.7 x 21.6

Calder Foundation, © 2010 Calder Foundation New York / ARS, New York, Photograph © Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, NY

What do these portraits say about Calder? Where do they fit in terms of his evolution as an artist?

While Calder participated in the widespread fascination with popular culture, he also directed his portraiture toward more meaningful relationships. A large proportion of Calder’s portraits depict fellow artists and art-world personalities whom Calder knew quite well, and these occupy a special place in his oeuvre. Because we recognize many of the sitters as well-known artists, our engagement as viewers is enhanced. Like no other category, these works invite our participation—and our curiosity. And they reveal much about Calder himself, about his attraction to fellow human beings, about his generosity, and above all, about his sense of humor.

Untitled (moblie with wire figure of Saul Steinberg)

Mobile of sheet metal, wire, string, and paint, c. 1954

110.5 x 152.4 x 45.7cm

Collection of Helen and Charles Schwab

Photograph by Ellen Page Wilson, © 2010 Calder Foundation, New York / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

Take the Portrait of Arthur Miller, c. 1972 (see image below): Calder drew this portrait directly on the wall of Miller’s barn during one of the playwright’s parties. With just a few strokes of the pen, Calder outlines Miller’s long face, with its wide slightly smiling mouth, and large nose, creating a likeness immediately recognizable as Arthur Miller. The friendship between Calder and Miller was based not on career interests; indeed, the two rarely discussed either theater or art, but on mutual respect and admiration. However, Miller admitted that he didn’t know what to make of Calder’s work “for a year or more after I first entered his studio in Roxbury.” It seems that what finally enabled him to “get” Calder was that Miller finally recognized the fundamental humanity in Calder’s work—in Miller’s words, that “this work of cold wire and sheet metal was sensuous, that the ever-shifting relationships within a mobile were refracting the same elemental and paradoxical forces in physics and human relations.” Such was the genius of Calder, that he was able to infuse his portraits with probing acuity and humor, poetry and humanity.

Arthur Miller

Felt-tip ink on painted gypsum board, c. 1972

Frame: 71.1 x 76.2 cm

Private Collection, © 2010 Calder Foundation New York / ARS, New York, Photograph © Calder Foundation, New York / Art Resource, NY

Where did the works included in the show come from?

Several works by Calder and many of the photographs and caricatures are in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery. Other works are on loan from museums including several from the Whitney Museum of American Art, the National Gallery of Art, The Museum of Modern Art, and the Chazen Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin, Madison; as well, some loans came from private collections. The Calder Foundation in New York is responsible for the greatest number of loaned works.

What do you hope the visitor takes away from this exhibition?

An appreciation of the art of Alexander Calder expanded beyond the mobiles and stabiles for which he is best known for. As well, a sense not only of his widely recognized light-hearted humor and playfulness, but also of the depth of character, human warmth and generosity of the artist, as expressed in his portraits.

Written by MutualArt.com staff

Top image: Alexander Calder with Edgar Varese (c. 1930) and Unknown man (1929), Sache, 1963

Ugo Mulas (1928-1973)

Gelatin silver print, 1963

Courtesy Ugo Mulas Archives, © Ugo Mulas Heirs. All Rights Reserved, Calder artwork in photo © 2010 Calder Foundation New York / ARS, New York