“I don’t think it is healthy for a photographer to altogether run away from clichés—just as I don’t think it is wise for any kind of artist to try and do something entirely new. We are all working within a language and tradition. To avoid that language is to speak gibberish. The best thing is to accept it, and maybe, if you’re lucky, expand it a little bit.”

—Alec Soth

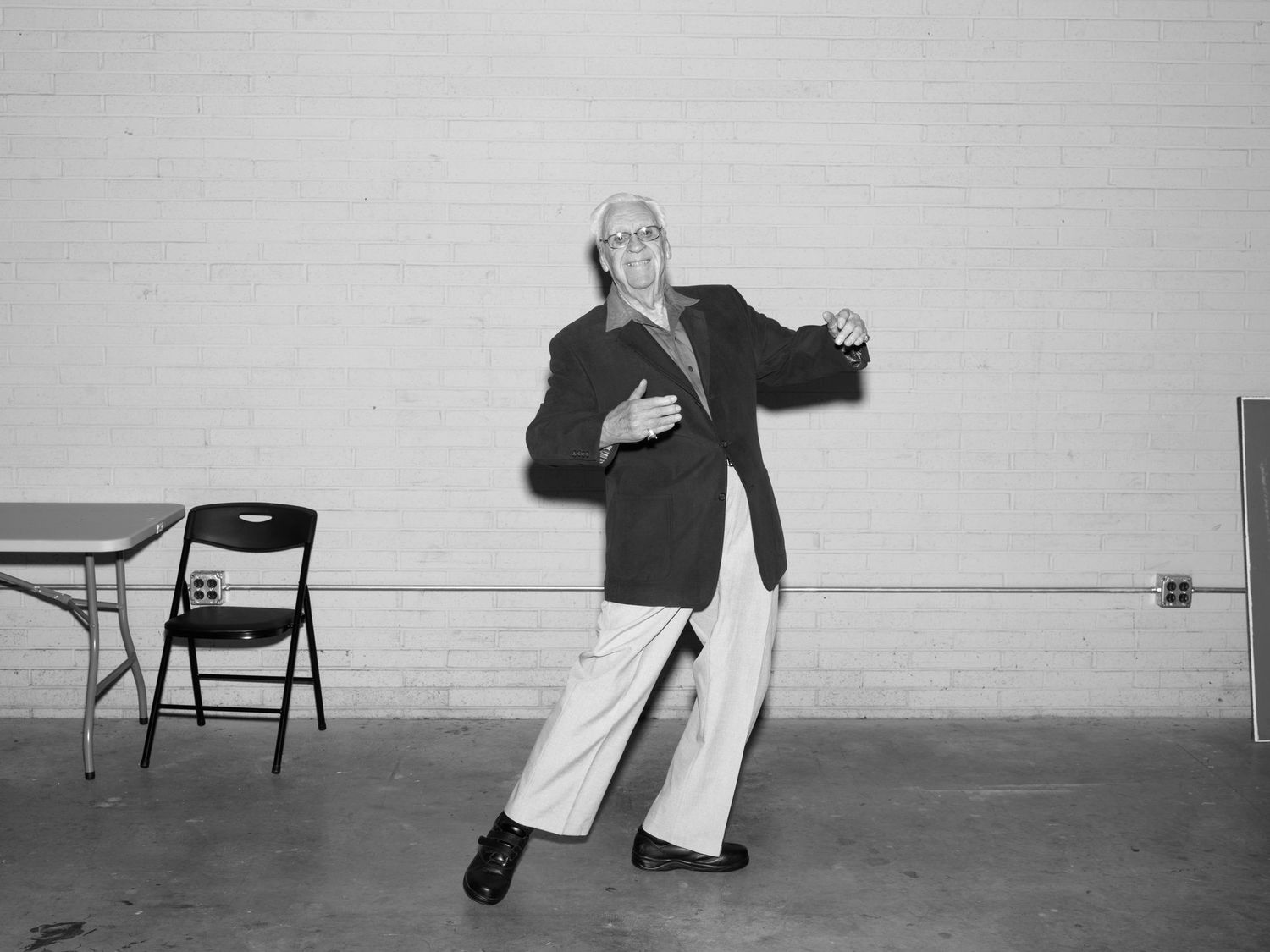

Alec Soth has been a beloved figure in the scene of contemporary photography since his landmark publication Sleeping by the Mississippi in 2004. That same year, his work was exhibited as part of the Whitney Biennial and he became a nominee at Magnum Photos. His career has flourished along diverse paths since then.

One major component of Soth’s output has been his photobooks—including Niagara, Broken Manual and Songbook. He has also worked on a self-publishing project called “Little Brown Mushroom,” which has produced dispatches, newspapers and much more. Along the way, he has also been commissioned for a wide range of editorial work, appearing repeatedly in The New York Times Magazine and many other publications.

Alexander Strecker emailed Soth to learn more about his changing views on photography and his advice for aspiring photographers. Read on to discover a flavor of Soth’s spare, direct wisdom—

LC: What initially drew you towards Magnum? In retrospect, the fit seems to make perfect sense, but in 2004, when you joined, it was probably more of a gamble on both sides.

AS: I’ve always been a bit distrustful of the art world, so I joined Magnum to broaden my horizons. More than looking for work, I was looking for community. As it is an international collective, I started having regular contact with photographers living all over the world. Magnum photographers also come from diverse aesthetic and professional backgrounds, so I’m regularly in touch with older street photographers, young war photographers, and so on.

LC: What/who were the key elements to your photographic education? I don’t just mean photographers—I’m thinking of key life experiences or music you listened to, or a writer who really formed your world view?

AS: I owe my life to my high school art teacher. He opened up an entire universe of learning that has never stopped. One of the artists he introduced me to was John Cage. I used to have dreams about meeting Cage. While that never happened, lately I’ve come to think of Cage as my greatest teacher.

LC: Your work is often compared to literature. You also have a particular fondness for poems, as your Instagram feed reveals. A quote from an old interview seems to indicate you thinking in these terms yourself—“Photography tends to be more fragmented. It’s more like poetry than writing a novel.”

AS: It’s true that I find poetry to be the medium most analogous to photography. Originally, this annoyed me, because I thought poetry was pretentious. But over time I’ve come to love it.

Like photography, poetry is about suggestion—it’s about leaving a place for the reader/viewer to fill in the gaps.

Like photography, poetry is about suggestion—it’s about leaving a place for the reader/viewer to fill in the gaps.

LC: On a related note, you seem to have an ongoing struggle around the idea of “narrative photography.” More recently, you’ve said you are moving away from narrative photography and from storytelling, after being its champion for years. Can you say more?

AS: I used to believe that storytelling was the most powerful tool for expression and was therefore frustrated with photography’s limited narrative capacity. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve gradually become less enamored with storytelling. These days, I’m not even sure I care that much about expression. Mostly I’m interested in simply paying attention.

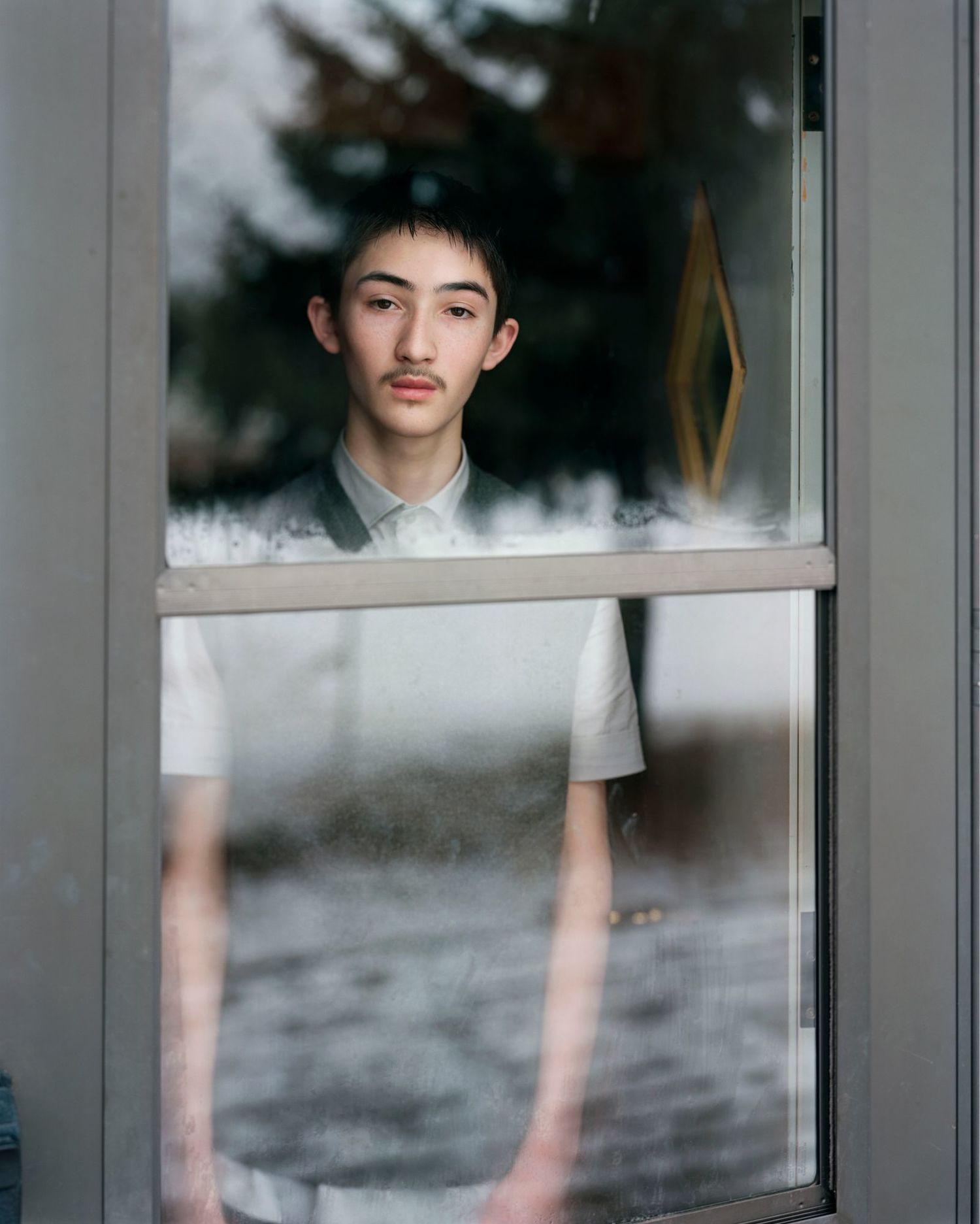

LC: It seems that your relation to portrait-making has also changed over time. These days, do you feel that your portraiture is more about separation/distance or about exchange/connection? How has that dynamic evolved?

AS: In the past, I would say my work was all about separation. But I recently made a 180-degree turn and am focused entirely on making connections. This effort hasn’t involved portraiture. I’m sure I’ll eventually return to making portraits, but my interest is currently elsewhere. It’s hard to say where this all will lead.

That being said, looking back on my work, it’s a relief to see that no matter how different each project might be in subject or technique, there’s always an underlying connection. This has given me the confidence to push out into vastly different territory without fearing that I’ll lose my voice.

LC: It’s often said that when we begin working in an art form, our ideas are bigger than our ability to execute them. There’s a gap between our taste/mind’s eye and what our hands can produce. What’s your advice for overcoming this gap?

AS: The gap can be excruciating. The only way I know of closing it is through time and attention. The key, I think, is to enjoy the process, struggle or not.

What I like to say is that if you want to be an artist, if you want to be a creative person, then you’re gonna have to be creative in how you put your career together. There isn’t a path. Part of the creativity is making your path.

LC: Assignment work has been very important for you during your career. These days, many photographers now follow the BFA/MFA route, rather than establishing themselves through paid, day-to-day shooting. How do you compare the pressures of learning through daily assignments vs. the critical distance that school affords?

AS: Just as I’m wary of making my income dependent on any one area of photography, I’m wary of suggesting a single educational path for young photographers. Everybody is different. The only advice I have is to sample as many different paths as possible. Take an art class, assist a commercial photographer, study on your own. If one of these paths speaks to you more than another, see where it takes you.

In short: try everything. Photojournalism, fashion, portraiture, nudes, whatever. You won’t know what kind of photographer you are until you try it. During one summer vacation (in college) I worked for a born-again tabletop photographer. All day long we’d photograph socks and listen to Christian radio. That summer I learned I was neither a studio photographer nor a born-again Christian.

Another year I worked for a small suburban newspaper chain and was surprised to learn that I enjoyed assignment photography. Fun is important. You should like the process and the subject. If you are bored or unhappy with your subject it will show up in the pictures. If in your heart of hearts you want to take pictures of kitties, take pictures of kitties.

What I like to say is that if you want to be an artist, if you want to be a creative person, then you’re gonna have to be creative in how you put your career together. There isn’t a path. Part of the creativity is making your path.

LC: Young photographers always ask—“How do I get my work out there? How do I establish myself, how do I become known?” I’m curious to hear how you’ve balanced the single-minded ambition necessary to succeed with the moment-to-moment presentness required by photography. How do you stay focused on the three-year plan (for example) but also make the space to take a walk on a sunny day?

AS: There are a variety of ways to make a reputation, but the only satisfying way is to make work that is both exceptional and authentic. And the only way to do that is to be as present as possible in process. You can’t do that if you are only thinking about future rewards (or failures).

When I make work, I make it for myself while simultaneously considering an audience. For me, each element of the equation enriches the other.

LC: As I prepared these questions, I was amazed how many times you’ve been interviewed. Hats off to your patience! So now I turn things around—is there any question you’ve never been asked but always wanted to answer?

AS: Ha, thanks for your acknowledgement. Nobody has ever asked me about the process of being interviewed itself. I would ask myself, “Why do I agree to do so many interviews?”

Much of the answer would likely be attributed to the vanity/fear that fuels most self-promotion. But I’ve come to find another value: Writers often say that they write in order to learn what they think. That’s a bit of the way I feel about interviews. If I try to answer the questions honestly, I often end the interview knowing more about myself than when I started. So thank you for making that happen.

—Alec Soth, interviewed by Alexander Strecker