“Remake, reuse, reassemble, recombine—that’s the way to go.”

The most counterfeited of all Andy Warhol’s work are his Marilyn prints. Thought it ironic somebody is selling a famous copy. For more money than his prints cost. Because it’s phony.

Wikipedia offers the best description of Sturtevant’s beginnings.

Sturtevant’s earliest known paintings were made in New York in the late 1950s. In these works, she sliced tubes of paint open, flattened them, and attached them to canvas. Most of these works contain fragments from tubes of several colors of paint, some have additional pencil scribbles and daubs of paint. Sturtevant was close friends with Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, both of whom own paintings from this period.

In 1964, by memorization only, she began to manually reproduce (or “repeat”) paintings and objects created by her contemporaries with results that can immediately be identified with an original, at a point that turned the concept of originality on its head. She initially focused on works by such American artists as Roy Lichtenstein, Frank Stella, Claes Oldenburg, Jasper Johns, James Rosenquist, and Andy Warhol. Warhol gave Sturtevant one of his silkscreens so she could produce her own versions of his Flowers paintings, Warhol Flowers (1969–70). When asked about his own technique, Warhol once said, “I don’t know. Ask Elaine.” After a Jasper Johns flag painting that was a component of Robert Rauschenberg’s combine Short Circuit was stolen, Rauschenberg commissioned Sturtevant to paint a reproduction, which was subsequently incorporated into the combine. In the late 1960s, Sturtevant concentrated on replicating works by Joseph Beuys and Duchamp. In a 1967 photograph, she and Rauschenberg pose as a nude Adam and Eve, roles originally played by Marcel Duchamp and Brogna Perlmutter in a 1924 picture shot by Man Ray.

In the early 1970s, Sturtevant stopped exhibiting art for more than 10 years. Pushback on her conceptual practice had begun, in fact, with Claes Oldenburg and his dealer, Leo Castelli, being publicly upset at her restaging The Store by Claes Oldenburg (1961) as The Store of Claes Oldenburg in 1967, just a few blocks away from where Oldenburg’s original had been staged.

As critic Eleanor Heartney wrote, “Sturtevant found her work met with resistance and even hostility. Her frustration culminated with a 1973 show at the Everson Museum of Art in Syracuse, New York. Titled “Sturtevant: Studies done for Beuys’ Action and objects, Duchamps’ etc. Including film,” the exhibition encompassed three rooms of objects and three of her early films that played off Warhol, Beuys and Duchamp. It was met with a deafening silence from the art world, precipitating her withdrawal.”

From the early 1980s she focused on the next generation of artists, including Robert Gober, Anselm Kiefer, Paul McCarthy, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres. She mastered painting, sculpture, photography and film in order to produce a full range of copies of the works of her chosen artists. In most cases, her decision to start copying an artist happened before those artists achieved broader recognition. Nearly all of the artists she chose to copy are today considered iconic for their time or style. This has given rise to discussions among art critics on how it had been possible for Sturtevant to identify those artists at such an early stage.

In 1991, Sturtevant presented an entire show consisting of her repetition of Warhol’s Flowers series.

Her later works mainly focus on reproductions in the digital age. Sturtevant commented on her work at her 2012 retrospective Sturtevant: Image over Image at the Moderna Museet: “What is currently compelling is our pervasive cybernetic mode, which plunks copyright into mythology, makes origins a romantic notion, and pushes creativity outside the self. Remake, reuse, reassemble, recombine—that’s the way to go.”

After feeling misunderstood by critics and artists, Sturtevant stopped making art for a decade. Her 2014 exhibition at MoMA was the first significant exhibition in the US in decades. Her last large-scale installation, The House of Horrors, has been on temporary display at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris since June 2015.

“In some ways, style is her medium. She was the first postmodern artist—before the fact—and also the last”, according to Peter Eleey, curator of her 2014 MoMA exhibition.

Elaine Sturtevant, Who Borrowed Others’ Work Artfully, Is Dead at 89

By Margalit Fox for The New York Times. May 16, 2014

Elaine Sturtevant, an American Conceptual artist whose work resembled that of Andy Warhol — and Roy Lichtenstein and Robert Rauschenberg and Marcel Duchamp and Jasper Johns and Keith Haring and a spate of other emblematic figures from the annals of contemporary art — died on May 7 in Paris. She was 89.

Her death was announced by her gallery, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, in Paris, where she had made her home since the early 1990s.

Ms. Sturtevant, known professionally simply as Sturtevant, was no forger. She was sometimes called the mother of appropriation art: the movement, which flourished in the 1980s and afterward, that makes new artworks by reproducing old ones. But with characteristic bluntness, she disdained the term, preferring to call her working method “repetition.”

“Manet had an intense dialogue with Velázquez, as did Picasso,” Bruce Hainley, the author of “Under the Sign of [sic],” a study of Ms. Sturtevant’s work published in January, said in an interview on Wednesday. “We don’t think of that as appropriation.”

As a replicator, Ms. Sturtevant was an original. A Sturtevant work is as instantly and uncannily recognizable as a Warhol silk-screen, say, or a Johns flag. But, at the same time, each in its own way is a deliberately inexact likeness of its more famous progenitor.

By holding up her imprecise mirror to a gallery of 20th-century titans, Ms. Sturtevant spent her career exploring ideas of authenticity, iconicity and the making of artistic celebrity; the waxing and waning of the public appetite for styles like Pop and Minimalism; and, ultimately, the nature of the creative process itself.

“In some ways, style is her medium,” Peter Eleey, the curator of a major exhibition of Ms. Sturtevant’s work opening at the Museum of Modern Art in New York this fall, said on Wednesday. “She was the first postmodern artist — before the fact — and also the last.”

The MoMA show, which runs from Nov. 9 through Feb. 22, represents the first significant exhibition of Ms. Sturtevant’s art in the United States in decades. Although her early work, from the mid-1960s, was well received, she came to feel misunderstood by the critics (and by many of the artists whose creations she reimagined) and stopped making art for about a decade.

Lately, Ms. Sturtevant has enjoyed a renaissance, with high-profile exhibitions at the Museum für Moderne Kunst in Frankfurt in 2004, the Moderna Museet in Stockholm in 2012 and the Serpentine Gallery in London last year.

She received a Golden Lion for lifetime achievement from the Venice Biennale in 2011.

In the beginning, Ms. Sturtevant’s work was praised for its wit, sly humor and desire to expose viewers to a blizzard of epistemological questions. “I create vertigo,” she liked to say.

Her first solo exhibition, at the Bianchini Gallery in New York in 1965, featured, among other pieces, a George Segal-like sculpture, silk-screens à la Warhol’s “Flowers” series (an obliging Warhol helped Ms. Sturtevant make them by lending her his original screen) and an ersatz Stella. In that show, and in her subsequent work, Ms. Sturtevant tacitly asked: When is a Warhol not a Warhol? When is it one — and what makes it so?

One answer, her art suggested, lay in the prototypes, which were, per the artistic preoccupations of the day, often copies themselves. (Think of Warhol’s soup cans.) If one borrows an image that is itself borrowed, her work suggested, then perhaps neither is truly original.

Another answer lay in the differences between the prototypes and Ms. Sturtevant’s renditions. Take the “Segal” sculpture in her first solo show, as Mr. Eleey explained:

“It’s a man in white plaster that signals to us it’s a ‘George Segal’ sculpture, but it’s not based on any real sculpture,” he said. “Likewise, in her first solo show in Paris in ’66, Lichtenstein’s ‘Crying Girl’ is something that he made as a print. She made it as a painting, and much larger.”

Ms. Sturtevant was, in essence, a composer writing variations on predecessors’ themes. But while no one ever took Brahms or Rachmaninoff to task for what they did to Paganini’s Caprice No. 24 for violin, the rules for visual art, Ms. Sturtevant found, were different — and the consequences severe.

Where Warhol had been sympathetic to her aims (queried about his silk-screening method, he was reported to have said: “I don’t know. Ask Elaine”), other artists were less so.

When, in 1967, just blocks from where the original had stood, Ms. Sturtevant opened her version of Claes Oldenburg’s “The Store” — a pop-up emporium featuring sculptures of ordinary objects he had erected a few years earlier on the Lower East Side of Manhattan — Mr. Oldenburg was not amused.

“Oldenburg is ready to kill me,” Ms. Sturtevant told Time magazine in 1969. “It all makes him dive up a wall.”

Over time, critical consensus turned against her, and Ms. Sturtevant withdrew from the New York art scene. She produced little from the mid-1970s to the mid-80s, re-emerging in 1986 with a show at White Columns, the alternative art space in Lower Manhattan.

Though she freely inhabited the artistic skins of others, Ms. Sturtevant took immense pains to obscure the particulars of her own history. Early in her career, she shed her given name like so much distracting baggage; to the end of her life, she countered interviewers’ biographical queries with a two-word response — “Dumb question” — insisting they focus on the work alone.

Elaine Frances Horan was born on Aug. 23, 1924, in Lakewood, Ohio, near Cleveland. She earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology from the University of Iowa, followed by a master’s in the field from Teachers College of Columbia University. In New York, she also studied at the Art Students League.

Ms. Sturtevant’s marriage to Ira Sturtevant, a Madison Avenue advertising executive, ended in divorce. Survivors include a daughter, Loren, and two grandchildren. Another daughter, Dea, died about 20 years ago.

In recent years, Ms. Sturtevant worked increasingly in video, producing installations — some incorporating footage shot directly off her television set — that bemoan what she saw as the deracinated human condition in the age of digital reproduction.

If, at bottom, Ms. Sturtevant’s art was designed to raise questions about originality, uniqueness and posterity, then there was a telling indication not long ago that it had done its work.

In 2007, an original “Crying Girl” by Lichtenstein — to the extent that one print in an edition of identical prints can be called an original — sold at auction for $78,400.

In 2011, Ms. Sturtevant’s canvas reworking of “Crying Girl” — the only Sturtevant painting of its kind in existence — sold for $710,500.

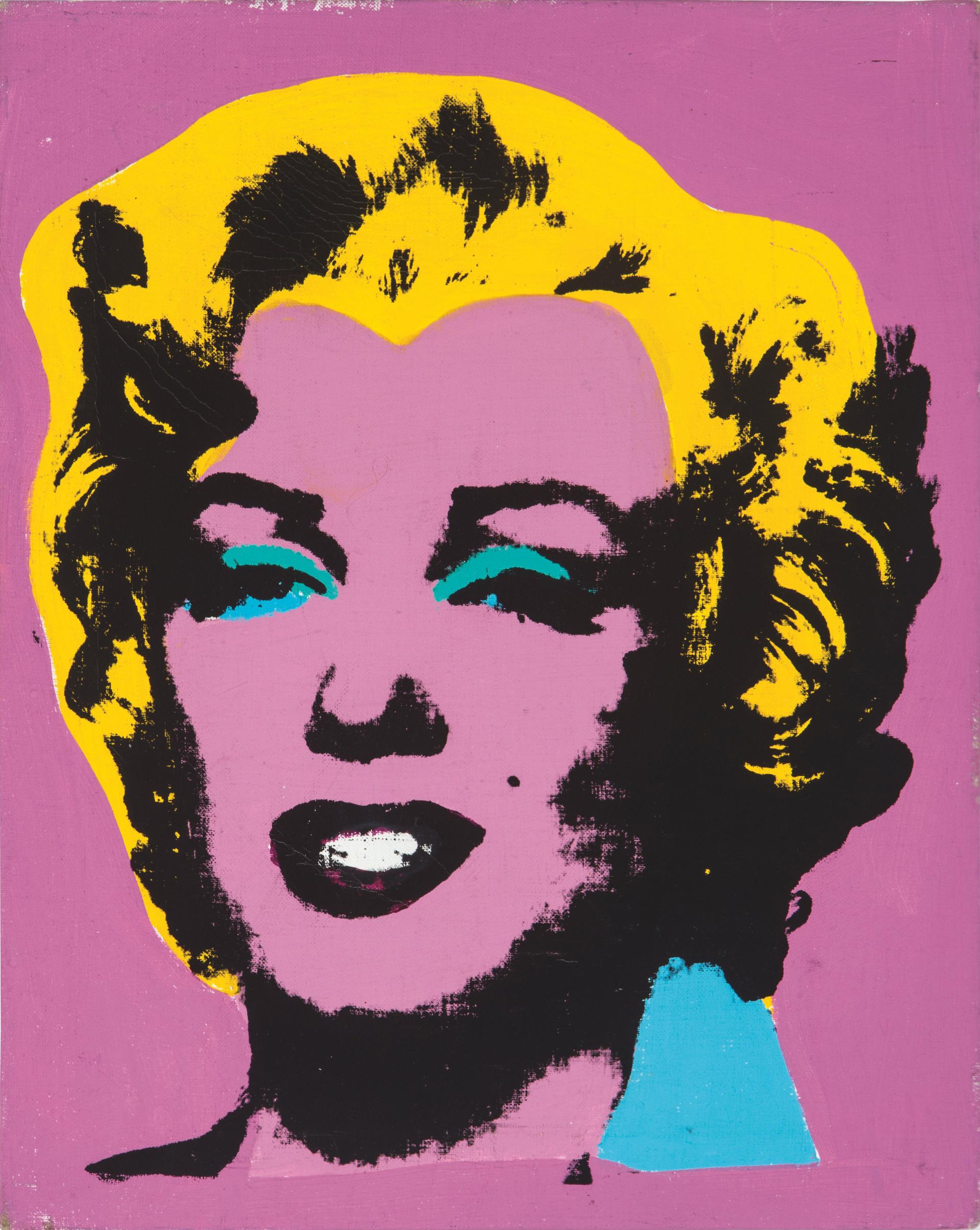

20 x 16.13 x 2 in. (50.8 x 40.97 x 5.08 cm.)

Est. $250,000–$350,000 US.

Get Your Own Sturtevant

By Johannes Vogt for Artnet Auctions.

Scholars have referred to Study for Warhol’s Marilyn from 1965 as “a Warhol that isn’t by Warhol,” but artist Sturtevant’s 1965 rendition of the classic Pop piece has a story all its own. Available for bidding now through November 19 in our Post-War & Contemporary Art sale on Artnet Auctions, Study for Warhol’s Marilyn shows Sturtevant examining notions of appropriation, creation, and authorship.

Born Elaine Sturtevant, the artist known professionally as simply Sturtevant began her radical practice in the 1960s. Although she is often associated with the Pictures Generation of appropriation artists from the 1970s and ‘80s––which included pioneers like Richard Prince, Richard Pettibone, and Sherrie Levine––Sturtevant remade and even exhibited appropriation works even earlier, in the 1960s, showcasing re-creations of works by Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Robert Rauschenberg, and of course, Andy Warhol.

Sturtevant’s appropriation of Warhol’s Marilyn happened soon after Warhol’s creation of the original work, which in itself appropriated an existing photo of the actress. To make her versions of the work, Sturtevant conferred with Warhol’s assistants, and even borrowed some of his actual silkscreens. Warhol once claimed Sturtevant knew his screening process better than the artist himself––when asked how he made his work, the Pop phenom replied, “Ask Elaine.”

As part of the experience of the work, Sturtevant intended the viewer to initially assume the author of the work to be Warhol. With this act, Sturtevant laid the foundation for generations of artists to come, and placed her practice in the direct line of succession from Marcel Duchamp and other conceptual artists.

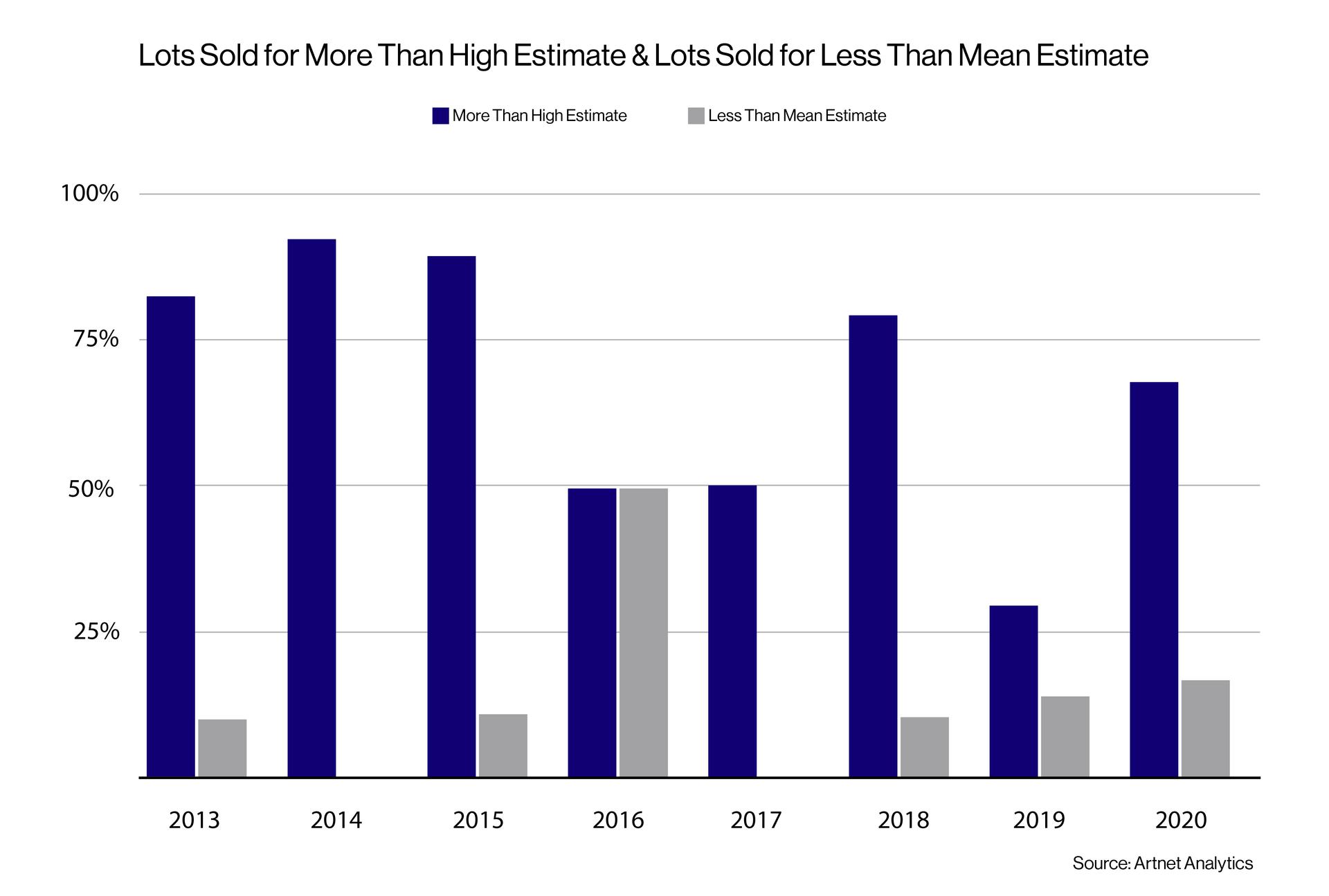

Works by Sturtevant consistently out-perform their high estimates at auction.

In recent years, Sturtevant’s work has achieved strong secondary market results. In 2014, a major retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art led to renewed interest in her work, and the same year, one of her Lichtenstein re-creations sold for $3.4 million at Christie’s (It’s worth noting that Lichtenstein, like Warhol with the silkscreen, loaned her one of his signature dot stencils).

This past year, four appropriations of artworks by Castelli-generation figures (including Warhol) sold for six-figures at or above their high estimates. Sturtevant’s Marilyns in particular have often achieved over $300,000 at auction in the last decade, and her estate’s representation by Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac ensures an international appeal and collector base.

From a historical perspective, Sturtevant’s use of the original Warhol silkscreen is outright revolutionary; her appropriation presented Warhol as a master of the Renaissance whose work needed to be replicated to be appreciated by the masses.

Estimated at $250,000–300,000, Study for Warhol’s Marilyn from 1965 represents an excellent opportunity for anyone looking to add a stellar mid-century work to their collection of 20th century art.

https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2014/11/24/image-3

Extra credit for homeschoolers.

From Oscar van Gelderen

In Lichtenstein, Frighten Girl, Sturtevant created a painting after one of Lichtenstein’s famous depictions of distressed women, in this case, Crying Girl. Lichtenstein’s version is a lithograph and was printed in 1963, but Sturtevant has rendered her woman in oil and graphite on canvas and in a much larger size. Differences aside, Sturtevant’s painting is strikingly similar to Lichtenstein’s print, from the color palette employed to the cropping of the figure, the style of the line and the use of Ben-Day dots on her skin.

Sturtevant’s work is not, however, an exact replica of the source artworks she selects. In Lichtenstein, Frighten Girl, Sturtevant has made calculated, if somewhat cryptic, changes: her female figure has bright blue eyes, part of the background is red instead of black and some of the detail lines in the hair and around the nose have been altered. One aspect that remains the same, though, is the emotional intensity and drama conveyed by both Girls with their wind-blown flaxen locks, plump cherry-red lips and matching nails and large glittering tears.

The consummate embodiment of tragedy, Sturtevant’s woman expresses heartrending anguish, fear and panic with her eyes perpetually locked on the viewer.

Whatever.