- 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Amsterdam University Medical Centers (UMC), University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 2Amsterdam Reproduction and Development Research Institute, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 3Department of Research Support–Medical Library, Amsterdam UMC, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Objective: To investigate the risk of preterm birth in women with a placenta previa or a low-lying placenta for different cut-offs of gestational age and to evaluate preventive interventions.

Search and methods: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CENTRAL, Web of Science, WHO-ICTRP and clinicaltrials.gov were searched until December 2021. Randomized controlled trials, cohort studies and case-control studies assessing preterm birth in women with placenta previa or low-lying placenta with a placental edge within 2 cm of the internal os in the second or third trimester were eligible for inclusion. Pooled proportions and odds ratios for the risk of preterm birth before 37, 34, 32 and 28 weeks of gestation were calculated. Additionally, the results of the evaluation of preventive interventions for preterm birth in these women are described.

Results: In total, 34 studies were included, 24 reporting on preterm birth and 9 on preventive interventions. The pooled proportions were 46% (95% CI [39 – 53%]), 17% (95% CI [11 – 25%]), 10% (95% CI [7 – 13%]) and 2% (95% CI [1 – 3%]), regarding preterm birth <37, <34, <32 and <28 weeks in women with placenta previa. For low-lying placentas the risk of preterm birth was 30% (95% CI [19 – 43%]) and 1% (95% CI [0 – 6%]) before 37 and 34 weeks, respectively. Women with a placenta previa were more likely to have a preterm birth compared to women with a low-lying placenta or women without a placenta previa for all gestational ages. The studies about preventive interventions all showed potential prolongation of pregnancy with the use of intramuscular progesterone, intramuscular progesterone + cerclage or pessary.

Conclusions: Both women with a placenta previa and a low-lying placenta have an increased risk of preterm birth. This increased risk is consistent across all severities of preterm birth between 28-37 weeks of gestation. Women with placenta previa have a higher risk of preterm birth than women with a low-lying placenta have. Cervical cerclage, pessary and intramuscular progesterone all might have benefit for both women with placenta previa and low-lying placenta, but data in this population are lacking and inconsistent, so that solid conclusions about their effectiveness cannot be drawn.

Systematic review registration: PROSPERO https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/, identifier CRD42019123675.

Introduction

Women with a placenta previa, overlying the internal os of the cervix, or a low-lying placenta, within 20 millimeter (mm) of the internal os of the cervix, have an increased risk of maternal and fetal complications during pregenancy (1, 2). The most important fetal complication is preterm delivery, which is the leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality (3–7). An estimated 11% of all world’s live births are preterm, whereas in women with placenta previa or a low-lying placenta this risk has been reported to be 2 to 4 times increased (8, 9). It has been speculated, that due to poor blood flow in the lower uterine segment and enlargement of the lower uterine segment in the third trimester, low-lying placentas detach more easily from the underlying decidua basalis. This can trigger a cascade of events ensuing vaginal bleeding, contractions, cervical effacement and dilation subsequently leading to preterm birth (1, 10–14). Thus, preterm births in women with placenta previa or a low-lying placenta are often caused by emergency deliveries for severe blood loss either with or without spontaneous onset of contractions. However, in order to avoid preterm abundant blood loss, they may be predominantly caused by scheduled cesarean sections before 37 weeks of gestation. Consequently, there is an increased risk of placenta previa in a subsequent pregnancy, as both a cesarean section in the obstetric history and placenta previa are both significant risk factors (15–19).Other known risk factors are multiple gestation, previous uterine surgical procedures, pregnancy termination or uterine artery embolization, increasing maternal age and parity, smoking, cocaine abuse and male fetus, of which some are independent (20–22). Especially given the increasing numbers of cesarean sections worldwide, it is important to consider this consequence as well to avoid future problems. Notably, in the case of a low-lying placenta, a trial of labor is often recommended unless major (bleeding) complications are present (2, 14, 23).

The risk of neonatal morbidity and mortality depends mainly on the severity of the prematurity (9, 24). It is important to counsel future parents considering the risks of preterm birth at different gestational ages and to consider preventive interventions. Therefore, we aim to review the current literature on the risk of preterm birth before 37, 34, 32 and 28 weeks of gestation in women with a placenta previa and in women with a low-lying placenta and to compare this between the two groups.

To a greater and lesser extent, cerclage, pessary and progesterone are known interventions that prolong gestation in women at high-risk of preterm delivery (25–27). Yet, the effectiveness of these preventive methods is largely unknown for pregnancies complicated by placenta previa or low-lying placentas (28). Therefore, in addition, we evaluate and describe the reported effect of intervention to preterm birth in this group of women.

Methods

Study design and systematic review protocol

This systematic review was reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement (Supplementary Information 1) (29). The review protocol was registered in the prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO: systematic review record CRD42019123675). This systematic review did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the commercial, not-for-profit or public sectors. As this article is a review, there was no direct patient- and public involvement in the study.

Participants, interventions and comparators

Women with a placenta previa or a low-lying placenta are the subject of this systematic review. When possible, we compared women with placenta previa to women without placenta previa or with women with a low-lying placenta. All possible preventive interventions for preterm birth described for these women were evaluated.

Search strategy and data sources

An information specialist (JL) performed a systematic search in OVID MEDLINE, OVID EMBASE, Web of Science, the Cochrane Controlled Register of Trials (CENTRAL) and the prospective trial registers clinicaltrials.gov and WHO-ICTRP from inception to December 6th, 2021. The search strategy consisted of controlled terms, including MESH-terms, and text words for placenta previa or low-lying placenta and preterm birth. Randomized controlled trials, cohort studies and case-control studies assessing preterm birth in women with placenta previa or low-lying placenta of the internal os in the second or third trimester were eligible for inclusion. Animal studies, conference abstracts, reviews and case reports were (safely) excluded if appropriate. We applied no date or language restrictions. We cross-checked the reference lists and the citing articles of the identified relevant papers in Web of Science and adapted the search in case of additional relevant studies. The bibliographic records retrieved were imported and de-duplicated in ENDNOTE. To evaluate the interventions a similar search strategy was performed on interventions, e.g. cerclage, pessary and progesterone to prevent preterm birth in women with placenta previa or low-lying placenta.

Study selection

Articles were selected in a staged process using the electronic screening tool RAYYAN. Two reviewers (CJ, CvD) independently screened titles and abstracts of all retrieved articles and selected potentially eligible studies. Both reviewers then independently examined the full-text papers. Disagreements about inclusions were resolved by consensus or by consulting a third reviewer (CK). Over the years, various definitions have been used for placentas that are implanted in the lower part of the uterus such as; minor and major placenta previa, placenta previa totalis, placenta previa partialis, placenta previa marginalis and low-lying placenta. In this review, we have used the currently recommended definitions for placenta previa, overlying the internal os of the cervix, and low-lying placenta, not overlying but within 20 mm of the internal os (30, 31). Aiming for the least heterogeneity between the included studies, we excluded articles that did not define placenta previa and/or low-lying placenta as such. Articles using the older terms of placenta previa partialis were considered as placenta previa, and placenta previa marginalis were considered as low-lying placenta. Studies that reported only the mean or median gestational age at birth were excluded. Gestational age at diagnosis, sonographer skills, types of equipment and standardized protocols for measuring placenta previa or low- lying placenta were not considered as exclusion criteria.

Data extraction

A predesigned data extraction form was used by two independent reviewers to retrieve study characteristics from each included study. For studies on risk of preterm birth, extracted preterm birth outcomes were proportions (based on given numbers of women with preterm birth and the total number of women) or odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for preterm birth below 37, 34, 32 and 28 weeks of gestation, or gestational age at delivery. Data was extracted separately for women with a placenta previa or a low-lying placenta. For intervention studies, we extracted data on gestational age at delivery, prolongation of gestation (i.e. the time from randomization to delivery), or odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals for preterm birth.

Data synthesis and analysis

Results of all studies reporting a proportion (or percentage, rate, incidence) of preterm birth before 37, 34, 32 and/or 28 weeks of gestation were pooled for women with placenta previa and for women with a low-lying placenta, as appropriate based on available data. Analyses of pooled proportions were performed using inverse of the Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation using metafor and meta packages in Rstudio version 3.6.1.For studies reporting the results for more than one group, we compared women with placenta previa to women without placenta previa or with women with a low-lying placenta. Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for the risk of preterm birth before 37, 34, 32, and 28 weeks of gestation.

To illustrate the effect of the interventions to prevent preterm birth in women with a placenta previa described in our overview, we calculated ORs with 95% CI for the risk of preterm birth or mean differences with 95% CI for gestational age at delivery and prolongation of gestation for women with and without preventive interventions (cerclage, pessary, progesterone). The meta-analyses were conducted using Review Manager version 5.3 from the Cochrane Collaboration. In all meta-analyses, a random-effects model was used.

Assessment of risk of bias

The quality of the studies was assessed with the Newcastle Ottawa scale. Articles with seven or more stars were found to be of high quality, four to five stars have moderate quality and articles with three or less stars were found to be of low quality. The Cochrane Handbook was used to judge the quality of each randomized controlled trial. To assess publication and small study bias, funnel plots were conducted, when at least 10 studies are available, because with fewer studies the power of the test is too low to distinguish chance from true asymmetry (Cochrane Handbook).

Results

Study selection and characteristics

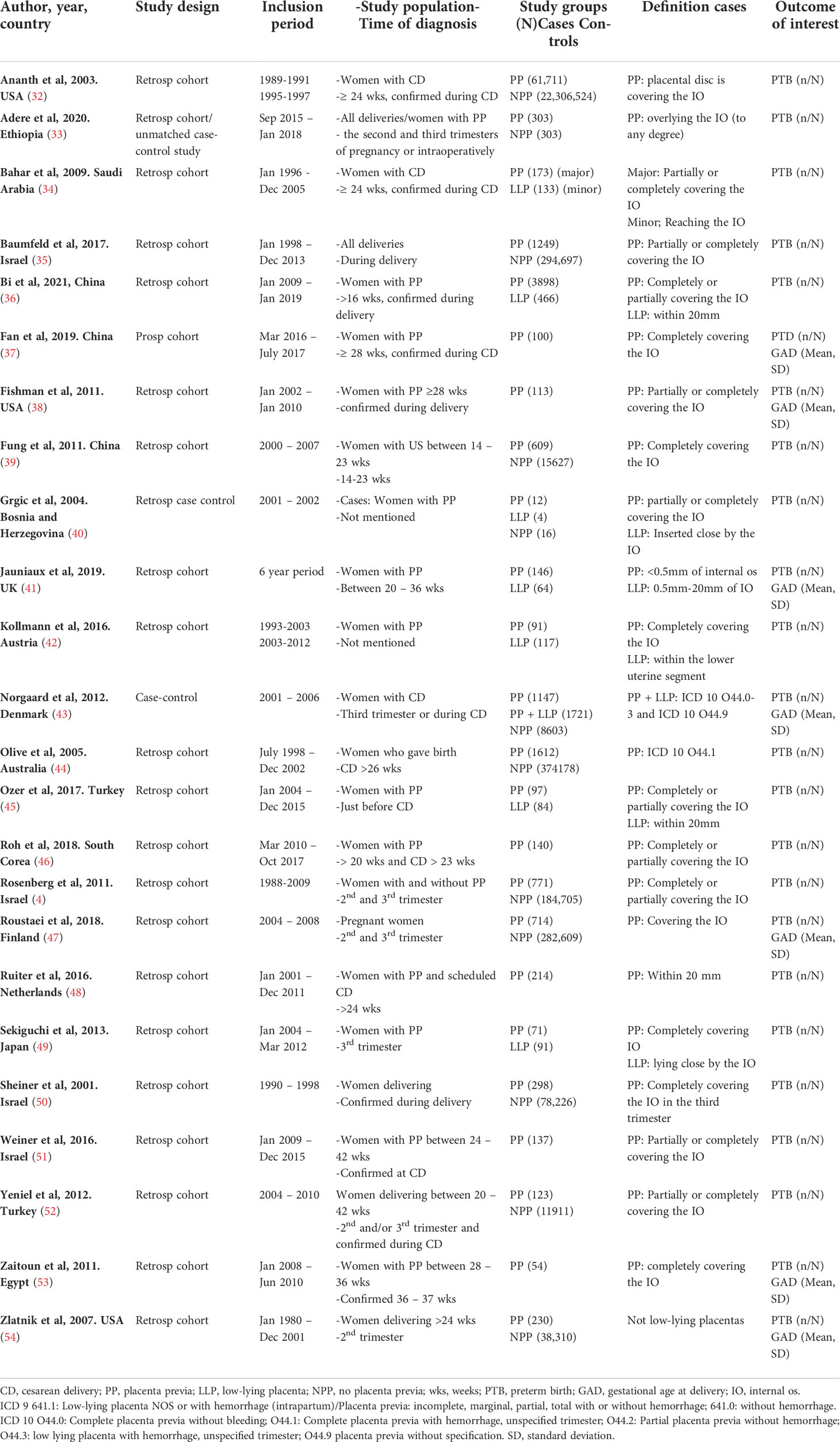

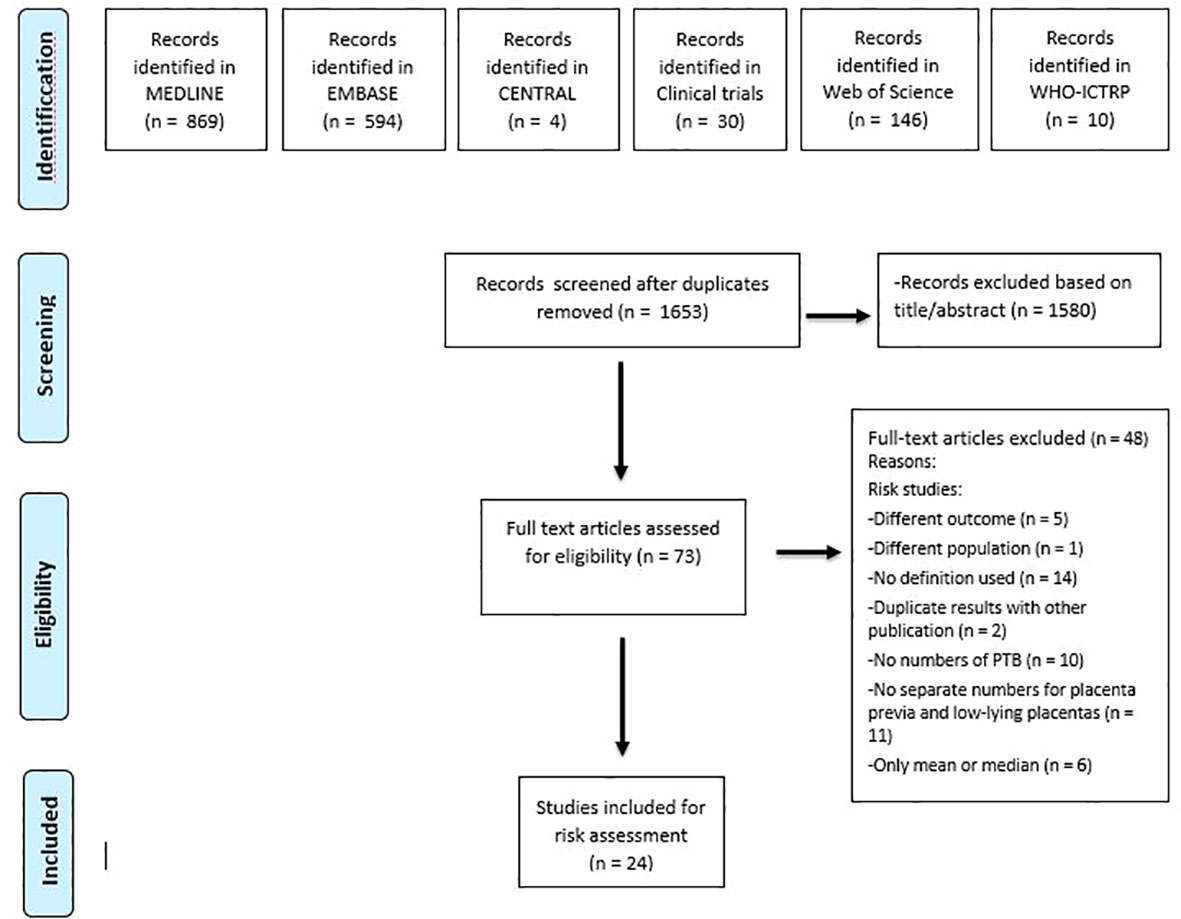

The search identified 1653 unique records. Of these, 24 were included based on full-text (4, 32–54). Figure 1 shows the flow-chart. All 24 studies reported on preterm birth in women with a placenta previa and 7 of the articles additionally reported on women with a low-lying placenta (35, 36, 40–42, 45, 49). Table 1 provides the baseline characteristics for the preterm birth studies.

Figure 1 Flow diagram showing selection of studies reporting on risk of preterm birth in women with placenta previa and/ or low-lying placenta and of studies reporting on interventions preventing preterm birth in women with placenta previa.

Assessment of risk of bias

The results of the quality assessment are shown in the Supplementary Information 3. Overall, the quality of included cohort and case-control studies was moderate to high. In general, the moderate score was due to the fact that there was no control group in the relevant cohort study. Within the included cohort studies, there may be publication or small study bias, as asymmetry was observed in the funnel plot of Figure 4A. In contrast, only 1 figure could be examined, given that fewer than 10 studies were included for the other comparisons.

Synthesized findings

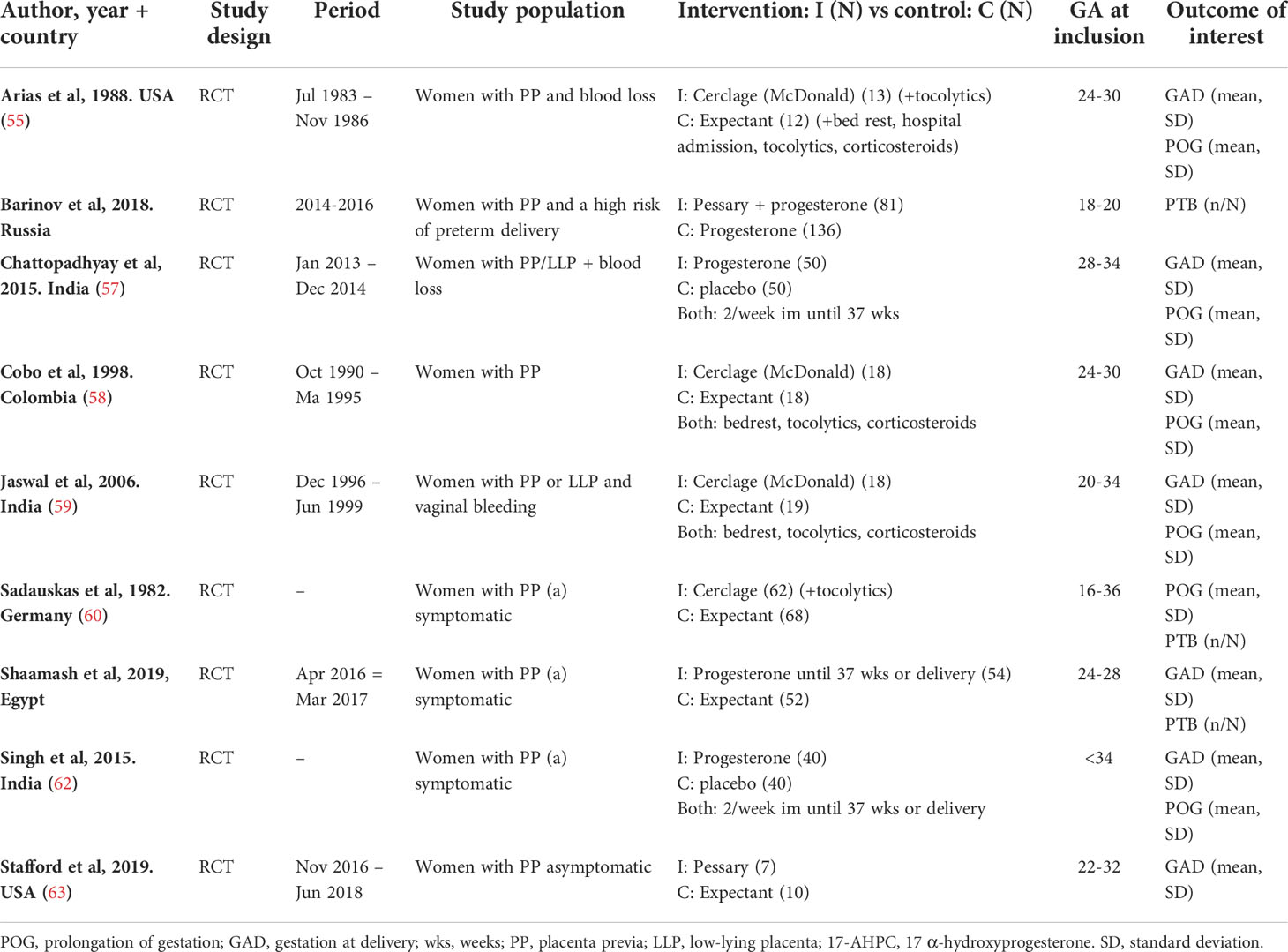

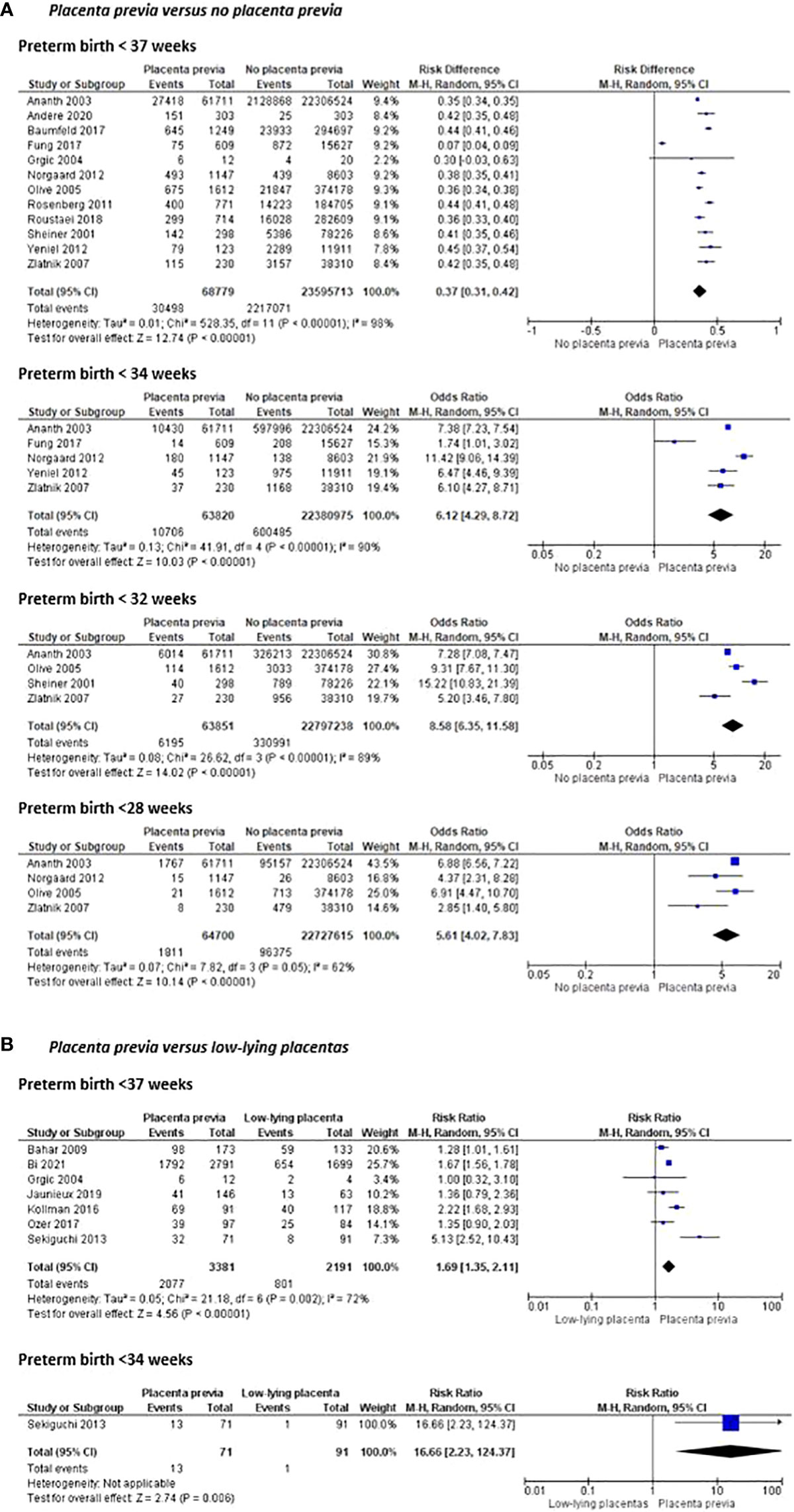

The pooled proportions of preterm birth for women with a placenta previa and low-lying placenta are shown in Figure 2. The pooled proportions before 37 weeks of gestation were 46% (95% CI [39 – 53%]) (20 studies) (4, 32, 34, 35, 37–50, 52, 54) for placenta previa and 30% (95% CI [19 – 43%]) (6 studies) (35, 40–42, 45, 49) for low-lying placenta, respectively. The proportions in these groups were 17% (95% CI [11 – 25%]) (9 studies) (32, 38, 39, 43, 48, 49, 51, 52, 54) and 1% (95% CI [0 – 6%]) (1 study) (49) respectively, for preterm birth before 34 weeks. For preterm birth before 32 and 28 weeks of gestation, studies reported only on women with a placenta previa. The pooled proportions were 10% (95% CI [7 – 13%]) (4 studies) (32, 44, 50, 54) and 2% (95% CI [1 – 3%]) (4 studies) (32, 43, 44, 54), respectively.

Figure 2 Individual and pooled proportions of risk of preterm birth before 37, 34, 32 and 28 weeks of gestation.

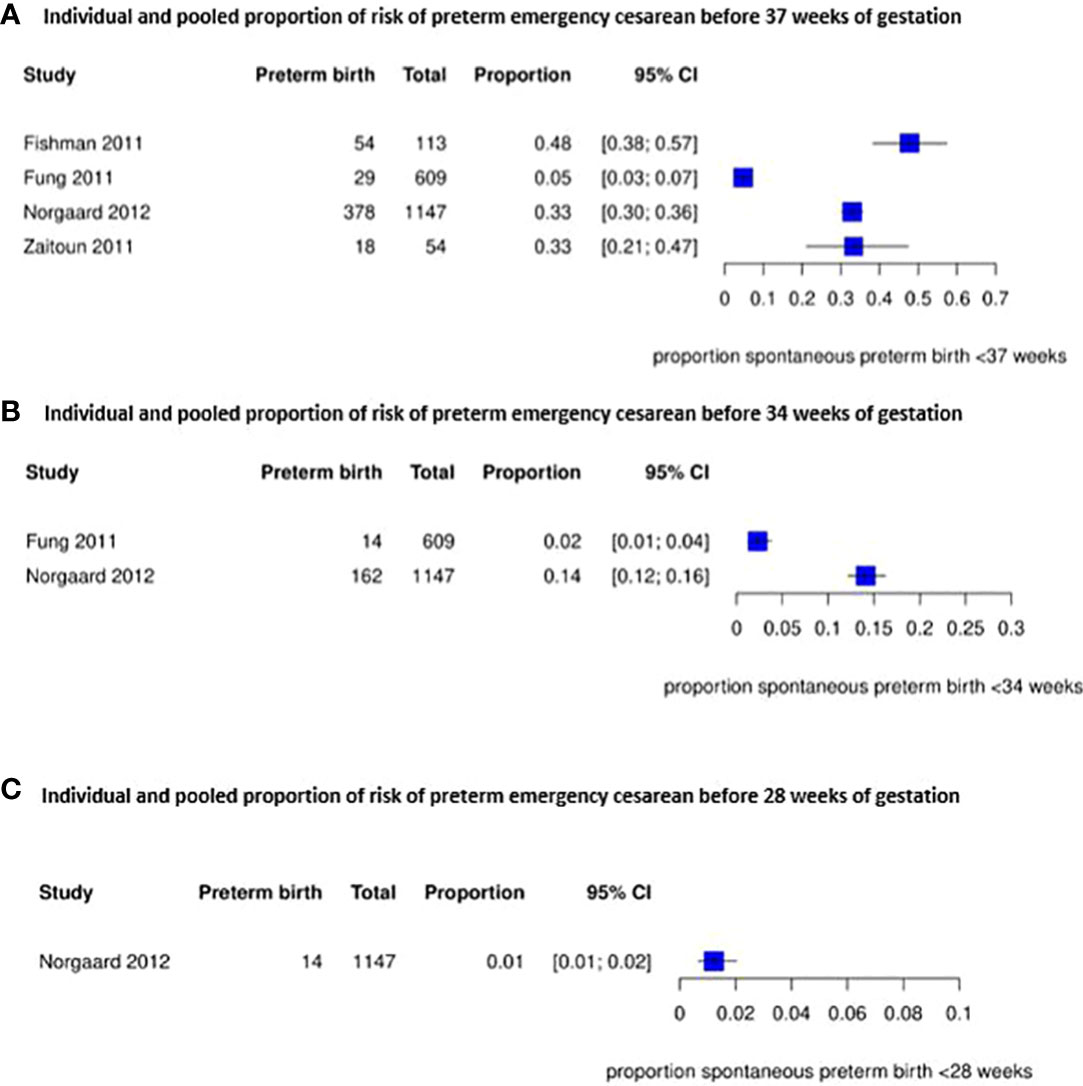

The risk of a preterm emergency cesarean in women with a placenta previa is shown in Figure 3. For this outcome we could not pool the results due to heterogeneity between the included studies, but proportions ranged from 5% to 48% before 37 weeks (4 studies) (38, 39, 43, 53), from 2% to 14% before 34 weeks (2 studies) (39, 43) and was 1% before 28 weeks of gestation (1 study) (43). Another study reported a higher risk of preterm emergency cesarean section before 34 weeks of gestation but no higher risk of a preterm emergency cesarean before 37 weeks of gestation in women with a placenta previa (39).

Figure 3 Individual and pooled proportion of risk of preterm emergency cesarean section before 37, 34 and 28 weeks of gestation for placenta previa.

Women with placenta previa were more likely to have a preterm birth before 37 weeks of gestation (risk difference 0.37 (95% CI [0.31-0.42]) and before 34, 32, and 28 weeks of gestation (OR 6.12 (95% CI [4.29-8.72]), OR 8.58 (95% CI [6.35 – 11.58]) and OR 5.61 (95% CI [4.02-7.83]) respectively) than women without placenta previa (Figure 4). Compared to women with al low-lying placenta, women with a placenta previa were also more likely to have preterm birth before 37 and 34 weeks of gestation (OR 1.69 (95% CI [1.35–2.11]) (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Risk of preterm birth before 37, 34, 32 and 28 weeks of pregnancy and mean gestational age at delivery between women with placenta previa and women without placenta previa or between women with placenta previa and women with a low-lying placenta.

Interventions to prevent preterm birth in women with a placenta previa

The interventions to prevent preterm birth were reported in nine studies (55–63). Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics for the intervention studies.

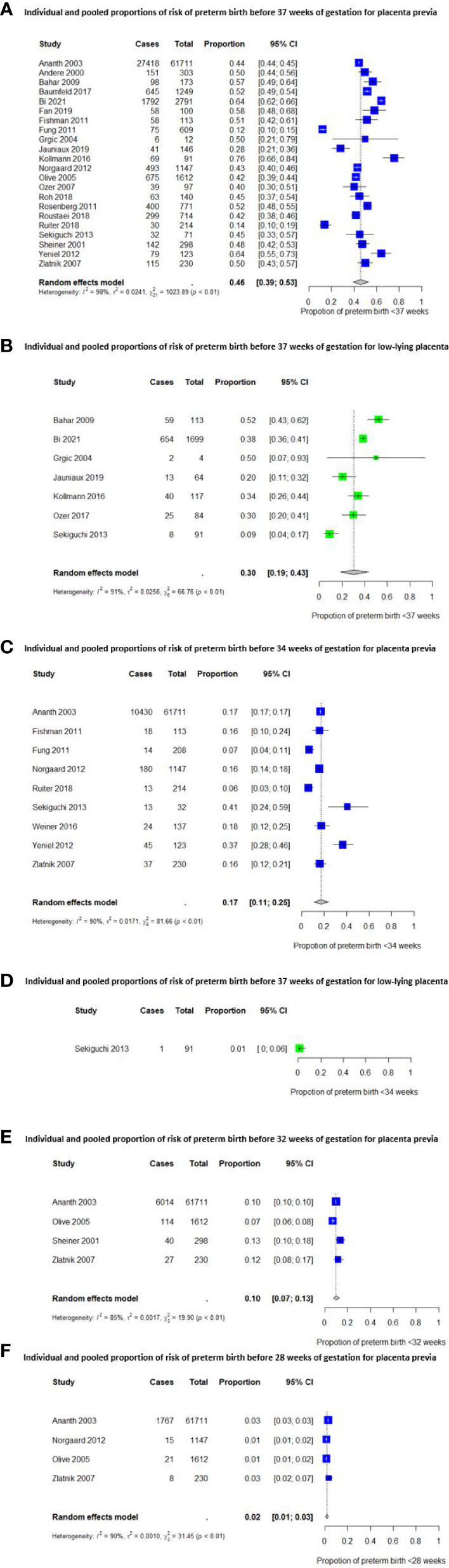

Progesterone –Three studies investigated the use of intramuscular progesterone in women with a placenta previa. No intervention studies were found in which vaginal progesterone was used as a treatment. All studies reported on the mean gestational age at delivery, which was significantly higher in the group of intramuscular progesterone. The pooled effect on the use of intramuscular progesterone showed a significant prolongation of gestation in favor of the women treated with progesterone in two studies (Figure 5) (57, 61, 62). One study showed a lower percentage of preterm birth in women using intramuscular progesterone compared to the non-progesterone group (37 vs 63% PTB P=0.007). Subsequently, in this study the mean number of bleeding attacks was significantly less in women with intramuscular progesterone (49.1 vs 67.3% P<0.001) (61).

Figure 5 Preventive interventions for preterm birth in women with a placenta previa or low-lying placenta.

Pessary – Two studies reported on a pessary as preventive intervention for women with a placenta previa. However, the first study reported the risk of preterm birth before 37 and 34 weeks, and the other study reported the mean gestational age at delivery in the two groups. Therefore, the results of the studies could not be pooled (56, 63).

Individually, the first study showed no significant difference in the mean gestational age at delivery between the group with a cervical pessary and the group with expectant management (36.5 (SD 1.23) vs. 36.0 (SD 2.00) weeks, p=0.032). However, the study was underpowered as the trial was stopped early before completion, secondary to slow enrolment and withdrawal of financial support by the sponsor. They did show however, that the number of antepartum admissions for bleeding was twofold higher in women randomized in the expectant management group (3 vs 8 admissions, not significant), suggesting that a cervical pessary placement in women with a placenta previa is associated with reduction of antepartum bleeding leading to preterm delivery (63).

The second study showed that in women with a placenta previa, already treated with progesterone because of a high risk of preterm birth due to other reasons, additional therapy of a pessary significantly reduced preterm delivery < 34 weeks (8.6 vs 23.5% P=0.031). Moreover, the use of a pessary in pregnancies with a placenta previa resulted in a three-fold reduction of the risk of bleeding during pregnancy and/or delivery (11.3 vs 33.1% bleeding, p=0.006) (56).

Cerclage – Four studies compared a cerclage with expectant management in women with a low-positioned placenta. The pooled effect of all four studies comparing cerclage with expectant management was in favor of cerclage considering the prolongation of gestation (mean difference of 3.55 weeks in favor of cerclage, 95% CI [1.57 – 5.54]) (55, 58–60). However, the pooled effect of the three studies reporting gestational age at delivery did not show any significant difference (mean difference 3.25 weeks in favor of cerclage, 95% CI [-0.19 – 6.70]) (55, 58, 59). Also the 1 study reporting odds of preterm birth before 37 weeks of gestation did not show any effect either (Figure 5) (60).

Discussion

Main findings

This review found a high risk of preterm birth across all gestational ages for women with a placenta previa and in women with a low-lying placenta. More specifically, a higher risk of preterm birth was found in women with placenta previa compared to women with a low-lying placenta and compared to women without placenta previa. Three interventions for the prevention of preterm birth were investigated of which cerclage, pessary and intramuscular progesterone might have benefit, but data in this population are lacking and inconsistent, so that solid conclusions about actual effectiveness cannot be drawn.

Strengths and limitations

First, a major strength of this study is the broad search that was performed thereby including studies originated from various countries without a restriction for publication year. Second, our findings are in line with a review dating from 2015 reporting risks for preterm birth of 44% and 27% for placenta previa and low-lying placentas, respectively (8). However, we were able to include more descriptive studies of placenta previa and of low-lying placenta. Additionally, we analyzed preterm birth risk at different gestational ages providing more detailed information. Since gestational age at birth is inversely correlated with neonatal morbidity and mortality, exclusively using results of preterm birth before 37 weeks does not reflect the magnitude of the problem in this group, e.g. a birth at 28 weeks does not hold the same fetal risks as a birth at 36 weeks of gestation (26). Besides, we did not only compare women with placenta previa with women without placenta previa, but also with women with a low-lying placenta. Another strength is our strict criteria considering the definition of a placenta previa or a low-lying placenta in terms of distance to the internal os, resulting in women with better comparable defined conditions. Finally, considering the preventive interventions, we were able to give an update of the current literature, since the latest review was published in the Cochrane database in 2003, which included only 2 articles (28). We added 7 more articles for this sub-question, not only reporting on cerclage but also on a cervical pessary and progesterone.

Several limitations require to be commented as well. In general, the available studies on the interventions to prevent preterm birth are often more outdated, being 14 to 38 years old. Variation in equipment, technique and terminology could have impact on the interpretation of data and reliability of their conclusions. In addition, there was a large difference between the size of the included studies (ranging from 16 patients to 22 million patients) and the included patients differed greatly in gestational age. This results in high to very high heterogeneity (I2 ranging between 62 -98%) between the included studies, which reduces the strength of evidence. Furthermore, there is only 1 outcome for which more than 10 studies could be included, so only 1 funnel plot could also be made to examine publication bias.

Although we aimed only to narrate on the possible interventions to prevent preterm birth in women with placenta previa, it is still important to address the limitations considering these studies. The randomized controlled trials had a low risk of attribution and reporting bias as the outcome data was complete and no selective reporting occurred. However, some studies had a higher risk of selection bias due to lack of allocation concealment and lack of random sequence generation. Blinding was most of the time not possible but it was unclear if this had any influence on the quality of the study. In addition, it is unclear what the role of publication bias might have been on the results. However, there are so few available studies per meta-analysis per intervention that there is too little data to create a funnel plot to interpret whether publication bias is indeed present. Most important, there is a large heterogeneity in the included studies, since the patients are included over a wide range of gestational ages and indications for interventions are highly heterogeneous. This weakens conclusions about their effectiveness considerably. The analyses compare only small (underpowered) number of patients that can produce misleading results and some only involve a single study or two small studies - which is limiting the validity of a “meta-” analysis and ensures that a sensitivity analysis to the between-study heterogeneity has no added value. The same applies to the cohort studies, where there is also considerable heterogeneity between the studies. The small numbers of patients per cohort, the large variation in gestational age at inclusion, and the large variation in (obstetric) history seem to contribute mainly to this.

Interpretation and implication

The well-recognized high risk of preterm birth for women with a placenta previa or low-lying placenta is comparable with or even higher than other known high-risk pregnancies, for example women with a history of spontaneous preterm birth (sPTB) have a risk of 15-30% on sPTB before 37 weeks of gestation in their index pregnancy (64). However, to this day the exact mechanisms are not unraveled. The two most plausible mechanisms seem associated with the cascade of placental detachment leading to (anticipated) antepartum blood loss and short cervical length. However, the reported risks of preterm birth in women with a placenta previa or low-lying placenta with and without antepartum blood loss differ between studies. The studies of Rosen et al. and Lam et al. contradict each other; where the first finds no difference in neonatal outcome between women with and without blood loss, the latter does, probably due to the gestational age at birth (65, 66). Our group previously evaluated factors that may predict an emergency delivery before the scheduled date in women with a placenta previa. We found that antepartum bleeding is an independent predictor for an emergency delivery in women with placenta previa, giving odds ratios of 7.5, 14 and 27 for one, two and three or more bleeding episodes, respectively (48). As for cervical length, a prospective cohort on the cervical length in women with placenta previa showed that women with a placenta previa and a cervical length of less than 30 mm, measured at 32 weeks of gestation or earlier if symptoms presented themselves, were three times more likely to delivery prematurely than women with a placenta previa and a cervical length over 30 mm. In addition, women with a placenta previa and a short cervix were more likely to develop antepartum blood loss (67).

Strong conclusions considering the interventions cannot be drawn, however we do suggest a benefit for progesterone, pessaries and cerclage. Progesterone acts primarily through maintaining uterine quiescence in the latter half of pregnancy, however the mechanism is unclear. Proximate to the onset of labor both term and preterm, progesterone activity withdrawals in the uterus. Therefore, progesterone supplementation in pregnancy may establish uterine relaxation, so it is reasonable to hypothesize that progesterone may be effective for women with a higher risk of preterm birth because of a placenta previa or low-lying placenta (57, 68, 69). The mechanism of a vaginal pessary is thought to be the correction of the utero-cervical angle by deviating the cervix posteriorly so the pressure from the uterus is redistributed (70, 71). Cervical cerclage is proven effective in high-risk pregnancies, mainly in women with cervical insufficiency, based on the additional support given by the suture. In case of a placenta previa, it has been suggested that the cerclage may reduce the tendency of the placenta to separate from the myometrium and thus preventing the blood loss that potentially start ends in preterm birth (26, 55). Three of the four studies demonstrated a significantly decreased rate of vaginal bleeding in the intervention group as compared to the control group (58–60).

However, given the previously described limitations, more profound and proper designed research of larger groups of patients, using the correct current definitions is necessary before incorporating preventive interventions in common practice.

Conclusions

In conclusion, both women with a placenta previa and a low-lying placenta have an increased risk of preterm birth. This increased risk is consistent across all severities of preterm birth between 28-37 weeks of gestation. Women with placenta previa have a higher risk of preterm birth than women with a low-lying placenta. Progesterone, cervical pessary and cervical cerclage seem potentially effective preventive interventions for women with a placenta previa or low-lying placenta, but data in this population are lacking and inconsistent, so that solid conclusions about their effectiveness cannot be drawn.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CJ, EL, and EP designed the paper outline. JH and AS conducted a preliminary search led by CJ. JL designed and performed a systematic search in consultation with CJ. CJ and CD conducted the search and consulted CK in case of disagreement. Data collection and analyses were conducted by CJ and CK. All authors (CJ, CD, JH, AS, JL, BK, EL and EP) critically reviewed subsequent paper drafts and approved the submitted version. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fendo.2022.921220/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Silver RM. Abnormal placentation: Placenta previa, vasa previa, and placenta accreta. Obstet Gynecol (2015) 126(3):654–68. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001005

2. Bronsteen R, Valice R, Lee W, Blackwell S, Balasubramaniam M, Comstock C. Effect of a low-lying placenta on delivery outcome. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol (2009) 33(2):204–8. doi: 10.1002/uog.6304

3. Daskalakis G, Simou M, Zacharakis D, Detorakis S, Akrivos N, Papantoniou N, et al. Impact of placenta previa on obstetric outcome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet (2011) 114(3):238–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.03.012

4. Rosenberg T, Pariente G, Sergienko R, Wiznitzer A, Sheiner E. Critical analysis of risk factors and outcome of placenta previa. Arch Gynecol Obstet (2011) 284(1):47–51. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1598-7

5. Patel RM. Short- and long-term outcomes for extremely preterm infants. Am J Perinatol (2016) 33(3):318–28. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1571202

6. Stensvold HJ, Klingenberg C, Stoen R, Moster D, Braekke K, Guthe HJ, et al. Neonatal morbidity and 1-year survival of extremely preterm infants. Pediatrics (2017) 139(3):e20161821. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-1821

7. Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Walsh MC, Carlo WA, Shankaran S, et al. Trends in care practices, morbidity, and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993-2012. JAMA (2015) 314(10):1039–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10244

8. Vahanian SA, Lavery JA, Ananth CV, Vintzileos A. Placental implantation abnormalities and risk of preterm delivery: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstetrics Gynecol (2015) 213(4 Suppl):S78–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.058

9. Blencowe H, Cousens S, Chou D, Oestergaard M, Say L, Moller AB, et al. Born too soon: the global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod Health (2013) 10 Suppl 1:S2. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-S1-S2

10. Oyelese Y, Smulian JC. Placenta previa, placenta accreta, and vasa previa. Obstetrics Gynecol (2006) 107(4):927–41. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000207559.15715.98

11. Hasegawa J, Nakamura M, Hamada S, Matsuoka R, Ichizuka K, Sekizawa A, et al. Prediction of hemorrhage in placenta previa. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol (2012) 51(1):3–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2012.01.002

12. Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. Lancet (2008) 371(9606):75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4

13. Romero R, Espinoza J, Kusanovic JP, Gotsch F, Hassan S, Erez O, et al. The preterm parturition syndrome. BJOG (2006) 113 Suppl 3:17–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01120.x

14. Wortman AC, Twickler DM, McIntire DD, Dashe JS. Bleeding complications in pregnancies with low-lying placenta. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med (2016) 29(9):1367–71. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2015.1051023

15. Ananth CV, Smulian JC, Vintzileos AM. The association of placenta previa with history of cesarean delivery and abortion: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol (1997) 177(5):1071–8. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(97)70017-6

16. Gilliam M, Rosenberg D, Davis F. The likelihood of placenta previa with greater number of cesarean deliveries and higher parity. Obstet Gynecol (2002) 99(6):976–80. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02002-1

17. Klar M, Michels KB. Cesarean section and placental disorders in subsequent pregnancies–a meta-analysis. J Perinat Med (2014) 42(5):571–83. doi: 10.1515/jpm-2013-0199

18. Lavery JP. Placenta previa. Clin Obstet Gynecol (1990) 33(3):414–21. doi: 10.1097/00003081-199009000-00005

19. Roberts CL, Algert CS, Warrendorf J, Olive EC, Morris JM, Ford JB. Trends and recurrence of placenta praevia: a population-based study. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol (2012) 52(5):483–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2012.01470.x

20. Ananth CV, Demissie K, Smulian JC, Vintzileos AM. Placenta previa in singleton and twin births in the united states, 1989 through 1998: a comparison of risk factor profiles and associated conditions. Am J Obstet Gynecol (2003) 188(1):275–81. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.10

21. King LJ, Dhanya Mackeen A, Nordberg C, Paglia MJ. Maternal risk factors associated with persistent placenta previa. Placenta (2020) 99:189–92. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2020.08.004

22. Long SY, Yang Q, Chi R, Luo L, Xiong X, Chen ZQ. Maternal and neonatal outcomes resulting from antepartum hemorrhage in women with placenta previa and its associated risk factors: A single-center retrospective study. Ther Clin Risk Manage (2021) 17:31–8. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S288461

23. Taga A, Sato Y, Sakae C, Satake Y, Emoto I, Maruyama S, et al. Planned vaginal delivery versus planned cesarean delivery in cases of low-lying placenta. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med (2017) 30(5):618–22. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1181168

24. Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, Chou D, Moller AB, Narwal R, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: a systematic analysis and implications. Lancet (2012) 379(9832):2162–72. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4

25. Abdel-Aleem H, Shaaban OM, Abdel-Aleem MA. Cervical pessary for preventing preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2013), CD007873. 31(5). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007873.pub3

26. Alfirevic Z, Stampalija T, Medley N. Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2017) 6:CD008991. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008991.pub3

27. Dodd JM, Jones L, Flenady V, Cincotta R, Crowther CA. Prenatal administration of progesterone for preventing preterm birth in women considered to be at risk of preterm birth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2013), CD004947. 31(7). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004947.pub3

28. Neilson JP. Interventions for suspected placenta praevia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2003) 2):CD001998. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001998

29. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PloS Med (2009) 6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

30. Reddy UM, Abuhamad AZ, Levine D, Saade GR, Fetal Imaging Workshop Invited P. Fetal imaging: executive summary of a joint Eunice Kennedy shriver national institute of child health and human development, society for maternal-fetal medicine, American institute of ultrasound in medicine, American college of obstetricians and gynecologists, American college of radiology, society for pediatric radiology, and society of radiologists in ultrasound fetal imaging workshop. Obstet Gynecol (2014) 123(5):1070–82. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000245

31. Dashe JS. Toward consistent terminology of placental location. Semin Perinatol (2013) 37(5):375–9. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2013.06.017

32. Ananth CV, Smulian JC, Vintzileos AM. The effect of placenta previa on neonatal mortality: a population-based study in the united states, 1989 through 1997. Am J Obstetrics Gynecol (2003) 188(5):1299–304. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.76

33. Adere A, Mulu A, Temesgen F. Neonatal and maternal complications of placenta praevia and its risk factors in tikur anbessa specialized and Gandhi memorial hospitals: Unmatched case-control study. J Pregnancy (2020) 2020:5630296. doi: 10.1155/2020/5630296

34. Bahar A, Abusham A, Eskandar M, Sobande A, Alsunaidi M. Risk factors and pregnancy outcome in different types of placenta previa. J Obstetrics Gynaecol Canada (2009) 31(2):126–31. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34096-8

35. Baumfeld Y, Herskovitz R, Niv ZB, Mastrolia SA, Weintraub AY. Placenta associated pregnancy complications in pregnancies complicated with placenta previa. Taiwan (2017) 56(3):331–5. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2017.04.012

36. Bi S, Zhang L, Wang Z, Chen J, Tang J, Gong J, et al. Effect of types of placenta previa on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a 10-year retrospective cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet (2021) 304(1):65–72. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05912-9

37. Fan D, Wu S, Ye S, Wang W, Wang L, Fu Y, et al. Random placenta margin incision for control hemorrhage during cesarean delivery complicated by complete placenta previa: a prospective cohort study. J Maternal-Fetal Neonatal Med (2019) 32(18):3054–61. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1457638

38. Fishman SG, Chasen ST, Maheshwari B. Risk factors for preterm delivery with placenta previa. J Perinat Med (2011) 40(1):39–42. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2011.125

39. Fung TY, Sahota DS, Lau TK, Leung TY, Chan LW, Chung TK. Placental site in the second trimester of pregnancy and its association with subsequent obstetric outcome. Prenat Diagn (2011) 31(6):548–54. doi: 10.1002/pd.2740

40. Grgic G, Fatusic Z, Bogdanovic G, Skokic F. Placenta praevia and outcome of delivery. [Croatian] Gynaecologia Perinatologia (2004) 13(2):86–8.

41. Jauniaux E, Dimitrova I, Kenyon N, Mhallem M, Kametas NA, Zosmer N, et al. Impact of placenta previa with placenta accreta spectrum disorder on fetal growth. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol (2019) 19:19. doi: 10.1002/uog.20244

42. Kollmann M, Gaulhofer J, Lang U, Klaritsch P. Placenta praevia: incidence, risk factors and outcome. J Maternal-Fetal Neonatal Med (2016) 29(9):1395–8. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2015.1049152

43. Norgaard LN, Pinborg A, Lidegaard O, Bergholt T. A Danish national cohort study on neonatal outcome in singleton pregnancies with placenta previa. Acta Obstetricia Gynecologica Scandinavica (2012) 91(5):546–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2012.01375.x

44. Olive EC, Roberts CL, Algert CS, Morris JM. Placenta praevia: maternal morbidity and place of birth. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol (2005) 45(6):499–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2005.00485.x

45. Ozer A, Sakalli H, Kostu B, Aydogdu S. Analysis of maternal and neonatal outcomes in different types of placenta previa and in previa-accreta coexistence. J Clin Analytical Med (2017) 8(4):341–5. doi: 10.4328/JCAM.4859

46. Roh H, Cho H. Prediction and clinical outcomes of preterm delivery and excessive haemorrhage in pregnancy with placenta previa. Ital J Gynaecol Obstetrics (2018) 30(4):13–22.

47. Roustaei Z, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K, Tuomainen TP, Lamminpaa R, Heinonen S. The effect of advanced maternal age on maternal and neonatal outcomes of placenta previa: A register-based cohort study. Eur J Obstetrics Gynecol Reprod Biol (2018) 227:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.05.025

48. Ruiter L, Eschbach SJ, Burgers M, Rengerink KO, van Pampus MG, Goes BY, et al. Predictors for emergency cesarean delivery in women with placenta previa. Am J Perinatol (2016) 33(14):1407–14. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1584148

49. Sekiguchi A, Nakai A, Kawabata I, Hayashi M, Takeshita T. Type and location of placenta previa affect preterm delivery risk related to antepartum hemorrhage. Int J Med Sci (2013) 10(12):1683–8. doi: 10.7150/ijms.6416

50. Sheiner E, Shoham-Vardi I, Hallak M, Hershkowitz R, Katz M, Mazor M. Placenta previa: obstetric risk factors and pregnancy outcome. J Matern Fetal Med (2001) 10(6):414–9. doi: 10.1080/jmf.10.6.414.419

51. Weiner E, Miremberg H, Grinstein E, Schreiber L, Ginath S, Bar J, et al. Placental histopathology lesions and pregnancy outcome in pregnancies complicated with symptomatic vs. non-symptomatic placenta previa. Early Hum Dev (2016) 101:85–9. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2016.08.012

52. Yeniel AO, Ergenoglu AM, Itil IM, Askar N, Meseri R. Effect of placenta previa on fetal growth restriction and stillbirth. Arch Gynecol Obstetrics (2012) 286(2):295–8. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2296-4

53. Zaitoun MM, El Behery MM, Abd El Hameed AA, Soliman BS. Does cervical length and the lower placental edge thickness measurement correlates with clinical outcome in cases of complete placenta previa? Arch Gynecol Obstetrics (2011) 284(4):867–73. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1737-1

54. Zlatnik MG, Cheng YW, Norton ME, Thiet MP, Caughey AB. Placenta previa and the risk of preterm delivery. J Maternal-Fetal Neonatal Med (2007) 20(10):719–23. doi: 10.1080/14767050701530163

55. Arias F. Cervical cerclage for the temporary treatment of patients with placenta previa. Obstetrics Gynecol (1988) 71(4):545–8.

56. Barinov SV, Shamina IV, Di Renzo GC, Lazareva OV, Tirskaya YI, Medjannikova IV, et al. The role of cervical pessary and progesterone therapy in the phenomenon of placenta previa migration. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med (2020) 33(6):913–9. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1509068

57. Chattopadhyay S, Roy A, Mandal A, Basu D, Bandyopadhyay S, Mukherjee S, et al. RANDOMISED CONTROL STUDY OF USE OF PROGESTERONE V/S PLACEBO FOR MANAGEMENT OF SYMPTOMATIC PLACENTA PREVIA BEFORE 34 WEEKS OF GESTATION IN a TERTIARY CARE CENTRE. J Evol Med Dent Sci-JEMDS (2015) 4(28):4862–7. doi: 10.14260/jemds/2015/705

58. Cobo E, Conde-Agudelo A, Delgado J, Canaval H, Congote A. Cervical cerclage: an alternative for the management of placenta previa? Am J Obstetrics Gynecol (1998) 179(1):122–5. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(98)70261-3

59. Jaswal A, Manaktala U, Sharma JB. Cervical cerclage in expectant management of placenta previa. Int J Gynaecol Obstet (2006) 93(1):51–2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.12.025

60. Sadauskas WM, Maksimaitiene DA, Butkewiczius SS. [Results of conservative and surgical treatment for placenta praevia (author’s transl)]. Zentralbl Gynakol (1982) 104(2):129–33.

61. Shaamash AH, Ali MK, Attyia KM. Intramuscular 17α-hydroxyprogesterone caproate to decrease preterm delivery in women with placenta praevia: a randomised controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol (2020) 40(5):633–8. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2019.1645099

62. Singh P, Jain SK. Evaluation of the effect of progesterone and placebo in parturient of symptomatic placenta previa: A prospective randomized control study. Int J Sci Stud (2015) 3(6):69–72. doi: 10.17354/ijss/2015/395

63. Stafford IA, Garite TJ, Maurel K, Combs CA, Heyborne K, Porreco R, et al. Cervical pessary versus expectant management for the prevention of delivery prior to 36 weeks in women with placenta previa: A randomized controlled trial. AJP Rep (2019) 9(2):e160–e6. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1687871

64. Mercer BM, Goldenberg RL, Moawad AH, Meis PJ, Iams JD, Das AF, et al. The preterm prediction study: effect of gestational age and cause of preterm birth on subsequent obstetric outcome. national institute of child health and human development maternal-fetal medicine units network. Am J Obstet Gynecol (1999) 181(5 Pt 1):1216–21. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70111-0

65. Rosen DM, Peek MJ. Do women with placenta praevia without antepartum haemorrhage require hospitalization? Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol (1994) 34(2):130–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.1994.tb02674.x

66. Lam CM, Wong SF, Chow KM, Ho LC. Women with placenta praevia and antepartum haemorrhage have a worse outcome than those who do not bleed before delivery. J Obstet Gynaecol (2000) 20(1):27–31. doi: 10.1080/01443610063417

67. Stafford IA, Dashe JS, Shivvers SA, Alexander JM, McIntire DD, Leveno KJ. Ultrasonographic cervical length and risk of hemorrhage in pregnancies with placenta previa. Obstetrics Gynecol (2010) 116(3):595–600. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ea2deb

68. Challis JRG, Matthews SG, Gibb W, Lye SJ. Endocrine and paracrine regulation of birth at term and preterm. Endocr Rev (2000) 21(5):514–50. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.5.0407

69. Norwitz ER, Robinson JN, Challis JR. The control of labor. N Engl J Med (1999) 341(9):660–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908263410906

70. Barinov SV, Shamina IV, Di Renzo GC, Lazareva OV, Tirskaya YI, Medjannikova IV, et al. The role of cervical pessary and progesterone therapy in the phenomenon of placenta previa migration. J Maternal-Fetal Neonatal Med (2019) 33:1–7. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1509068

Keywords: placenta previa, low-lying placenta, preterm birth, cerclage, pessary, progesterone, preventive interventions

Citation: Jansen CHJR, van Dijk CE, Kleinrouweler CE, Holzscherer JJ, Smits AC, Limpens JCEJM, Kazemier BM, van Leeuwen E and Pajkrt E (2022) Risk of preterm birth for placenta previa or low-lying placenta and possible preventive interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 13:921220. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.921220

Received: 15 April 2022; Accepted: 10 August 2022;

Published: 02 September 2022.

Edited by:

Karel Allegaert, University Hospitals Leuven, BelgiumReviewed by:

Guoli Zhou, Michigan State University, United StatesTobias Nijman, Leiden University Medical Center, Netherlands

Gabriele Saccone, Federico II University Hospital, Italy

Copyright © 2022 Jansen, van Dijk, Kleinrouweler, Holzscherer, Smits, Limpens, Kazemier, van Leeuwen and Pajkrt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Charlotte H. Jansen, c.h.jansen@amsterdamumc.nl

Charlotte H. J. R. Jansen1,2*

Charlotte H. J. R. Jansen1,2* Charlotte E. van Dijk

Charlotte E. van Dijk Elisabeth van Leeuwen

Elisabeth van Leeuwen