Even as we face climate breakdown, cities continue to be shaped by the automobile and a reliance on fossil fuels

A recent promotional video explaining The Line in Neom – a linear city in Saudi Arabia initially proposed in October 2017 – came under heavy criticism from architecture critics and academics. In his scathing critique of the project in the Financial Times, Edwin Heathcote described the project as ‘dystopia portrayed as utopia’. However, the project has also been uncritically celebrated for its supposed zero‑carbon emissions and sustainable design. The video portrays a city made up of a 200‑metre‑wide and 500‑metre‑high mirror‑glass building that stretches for approximately 100 miles through the middle of the Tabuk desert. The linear design of Neom is claimed by its architects to reduce the physical footprint of the city by 95 per cent, thus ‘making space for nature’, and is designed without roads.

The megaproject is the undertaking of an autocratic state that draws its power and wealth from Aramco, one of the largest fossil fuel corporations in the world. This contradiction between the design and ambition of the building raises the important question of what ‘zero emissions’ really means, and the contradictions of the fossil urbanism at its heart. The claimed zero‑emission design of the Neom project relies on the capital surpluses generated through the reproduction of what Andreas Malm calls ‘fossil capitalism’ elsewhere.

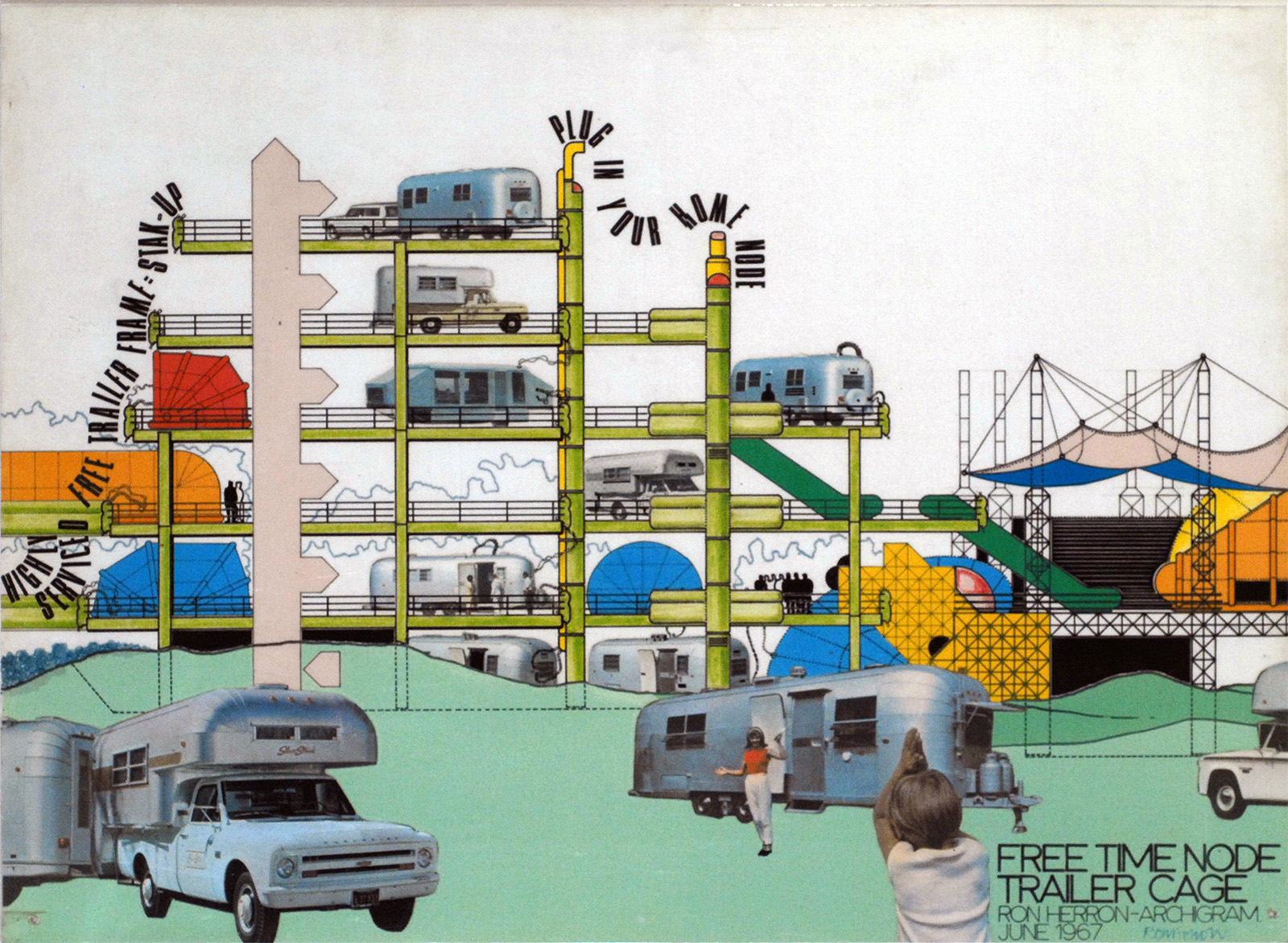

Despite decades of extensive critique – Archigram’s Free Time Node Trailer Cage dates from 1967 – fossil urbanism is booming

Credit: © Ron Herron Archive. All Rights Reserved, DACS/Artimage 2022

The recent reproduction of fossil urbanism at Neom is the most recent manifestation in the long history of complicity of architecture and architects in the reproduction of fossil urbanism, especially in conjunction with the strategic philanthropy of the companies that have benefited from it. Le Corbusier’s unrealised Plan Voisin, designed in the 1920s around automobility, was sponsored by the Voisin motor company, and his plans for the linear city of Algiers from the 1930s would very well resonate with the architectonics of Neom. Frank Lloyd Wright also developed his ideas for the agri‑industrial utopia of Broadacre City in the 1930s, around the same time that the US Interstate Highway System colonised the American countryside with a mobile settler population.

While never realised, Broadacre City provided an imaginary for banal and generic spatial production along the lines of the Jeffersonian Grid, what Keller Easterling calls the ‘organisation space’ that was implanted through the US Interstate Highway System during the interwar and postwar periods, helping stretch fossil urbanisms across the American countryside. Numerous cities, such as Delhi, Mumbai and Cairo, have been designed for extensive automobility through Ford Foundation‑funded initiatives authored by planners such as Albert Mayer from the American Regional Planning Association. These cities are not only the smokestacks of fossil capitalism today; the notion of private property, established through the enclosure of agrarian land and commons across the extensive urban fabrics of these cities,is heavily dependent on automobiles and fossil capitalism, and their large-scale expansion highlights that fossil capitalism continues to serve as the crucial glue holding property relationships together.

‘Instead of embracing the alternatives of degrowth, problems are being resolved as they always have been: by going to the deeper and further frontiers of fossil capitalism’

Some architecture critics and theoreticians have in fact celebrated fossil urbanisms and autopias, such as the documentary celebrations of fossil urbanism by Denise Scott Brown, Robert Venturi and Steven Izenour in Learning from Las Vegas from 1972, and the autopia of LA by Reyner Banham in Los Angeles: The Architectureof Four Ecologies from 1971.

But there has also been a tradition of radical critiques of fossil urbanisms, suchas in Ron Herron’s Free Time Node Trailer Cage from 1967 or Michael Webb’s Cushicle from 1964, which attempted to deconstruct the automobile and fossil capitalism dependency in architecture. The journalistic writings of Jane Jacobs in the 1960s helped disable Robert Moses’s attempts to implant expressways in the city of New York. However, although successful in resisting expressway construction in New York, this famous showdown has been criticised for its NIMBYist approach; there is opposition to fossil urbanism in the city centre, but it is apparently OK if it is replicated elsewhere. More recently, Neeraj Bhatia and Mary Casper have explored the afterlives of extractive fossil urbanism in The Petropolis of Tomorrow (2013), in which they examine the infrastructure, landscape, urbanismand architecture of offshore petroleum extraction in Brazil and speculate on what will happen to these infrastructures when petroleum runs dry.

Automobiles have shaped cities and landscapes for more than a hundred years: the Trans‑Amazonian Highway, first cut through the Amazon rainforest in the 1970s, is currently undergoing extensive renovation

Credit: NELSON ALMEIDA / AFP / Getty

The intensification of the violence of planetary phenomena – such as wildfires, floods, droughts, heat waves and cyclones that have become a profound part of the everyday realities of the urban majorities across the world – has made thinking ata planetary scale inevitable. There has been a corresponding radical shift in the politics of the current era, which historian Dipesh Chakrabarty describes as ‘the planetary age’. The upending of the certainty of the Holocene has forced a large portionof humanity to regularly confront the disjuncture between human and deep time, the planet and its many human worlds, and therefore to question the fossil urbanism that forms the basis of the multiple intersectional crises facing the planet.

As a result, there has been a new waveof direct action against fossil urbanism;the Trans‑Amazonian Highway, for instance, is often blocked by Indigenous people protesting against state action. Similarly, earlier this year, activists from Renovate Switzerland blockaded an Autobahn outside Lausanne to highlight the complicity of fossil urbanism in the climate crisis. Architectural degrowth movements, such as Neustart Schweiz, are looking at ways to retool and repair the existing architecture of fossil urbanism to become new localisms, instead of the production of new utopias that will only further reproduce fossil urbanism without resolving it.

In 2018, Elon Musk’s personal car, a Tesla Roadster, was launched into orbit as part of a marketing campaign

Credit: Space X

Regardless of these growing concerns in public consciousness, there has been a trend of postcolonial states, such as India, Brazil, China and Peru, pushing fossil urbanism asa model of growth under late capitalism. Projects such as the Trans‑Amazonian Highway and the Plan Puebla Panama in Central America, the Bharatmala highway corridor programme in India, and One Belt, One Road in China are pushing the state space of fossil urbanism into fertile agrarian regions and primal forests across the world. These states replicate and reproduce the economic development through fossil capitalism pursued by erstwhile colonial powers with projects that are accelerating and intensifying the planetary impact of climate change. Such megaprojects are often justified using the same carbon technocratic discourse as at Neom – of growth through zero emissions. Such discourses uphold the myth that the reproduction of fossil urbanism is possible by shifting its compensatory landscapes elsewhere on the planet, such as wind turbines on Greek islands and in the North Sea, solar arrays in the Sahara Desert, or compensatory forests on the subsistence agricultural landscapes of India and Central America.

The ongoing war in Ukraine has turned fossil capitalism into a dinnertime conversation. Populations in Western Europe and North America, who have enjoyed an unperturbed bourgeois lifestyle since the Second World War, are suddenly confronted with a scenario of not having homes heated or hot water running from taps as a ‘tough winter’ sets in. As Russia threatens to turn the fossil energy taps off, the ending of subsidies afforded by fossil capitalism confronts liberal democracy. But instead of embracing the alternatives of degrowth and addressing the private property paradigm at the heart of current intersectional crises, problems are being resolved as they always have been: by going to the deeper and further frontiers of fossil capitalism, by turning to even more violent and ecologically destructive ways of extraction such as fracking. The carbon technocracy, and the complicity of architecture and spatial practice within it, is preparing society for what American writer Roy Scranton calls ‘learning to die in the anthropocene’, rather than showing a way forward from the extractive property relations forged under fossil capitalism. Elon Musk’s Starman, mounted on a Tesla electric car looking back at Earth in a recreation of the Earthrise moment for the planetary age, helps us realise how close we are to such a dystopia becoming a reality.

Lead image: Le Corbusier’s unrealised Plan Voisin from 1925, sponsored by the Voisin motor company, was structured around wide roads to increase traffic capacity. Credit: Fondation Le Corbusier

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design

Architectural Review Online and print magazine about international design