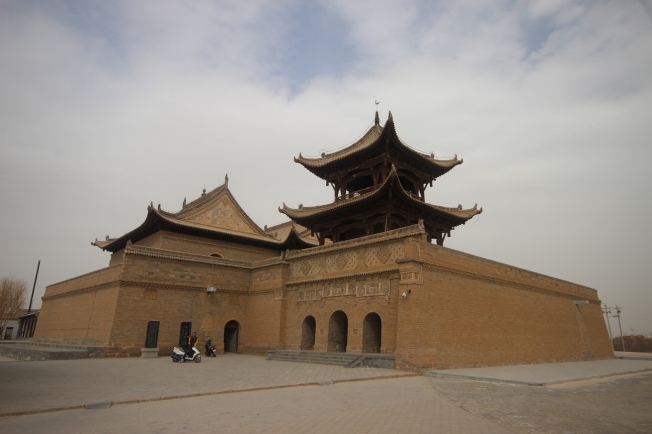

Tongxin’s Great Mosque dates back to the Ming Dynasty (1368 – 1644). Today is one of the best-preserved imperial-era mosques in China.

The Great Mosque first impresses with how distinctly un-mosque like it looks. Lets not forget the previous entry in this CNY series, in which I noted that Tongxin’s skyline is dominated the emerald domes and minarets of the city’s dozen or more other mosques, all of which are more obviously places of Muslim worship. I was a Chinese history major, but I must admit I don’t know the break in history after which they stopped building mosques in recognizably Chinese forms and started building them in a more international style. Regardless, on it surface Tongxin’s Great Mosque looks like any number of other traditional Chinese buildings, and uninformed I might even have conflated it with some other kind of Chinese temple.

I saw almost no one while approaching the mosque. There was no ticket booth, gate, or other directions for tourists, leading me to wonder whether I was welcome to venture inside. I wandered around outside a bit waiting for someone to show up so I could ask.

Around this time I announced to my family on WhatsApp that I was visiting a centuries’ old mosque. My mother asked if I had heard the Muslim call to prayer. As if on cue, an unseen loudspeaker on the mosque’s roof blared a recitation of the call to prayer, loud enough to be heard for miles. I recorded a few seconds on my phone and sent it to the family via WhatsApp, saying “There you go.”

After the call a few Hui men pedaled up on bikes. I asked one entering the mosque if it was alright for an outsider like me to go in, and he said sure. I followed him up a dark staircase onto the mosque grounds proper, which are situated on top of a stone platform over thirty feet high.

Inside I found a set of halls arranged around a courtyard that were reminiscent of countless other temples I had visited in China. The Islamic differences were all in the details, such as the Arabic inscriptions and other decorations in the pictures above.

I wandered around the grounds for a bit and took advantage of the raised vantage point to get some photos of the surrounding city. It was quite tranquil, except for a few minutes when a half dozen kids from town ran up into the grounds chasing each other and screaming.

Eventually I was joined by a Chinese tourist who was braver than I, and asked a mosque attendant whether she could be let into the main prayer hall. I was surprised when he acquiesced, since I had been rejected in no uncertain terms when approaching the prayer halls of other old mosques in China. Not to be left out this time, I quickly removed my dust-covered shoes and followed them in.

The main prayer hall (plus a couple of adjunct halls) supposedly can accommodate up to 1,000 people, but on this afternoon there appeared to be no such need. The attendant let us wander around and take photos as we pleased, though I tried to avoid going nuts with documenting such a rare visit.

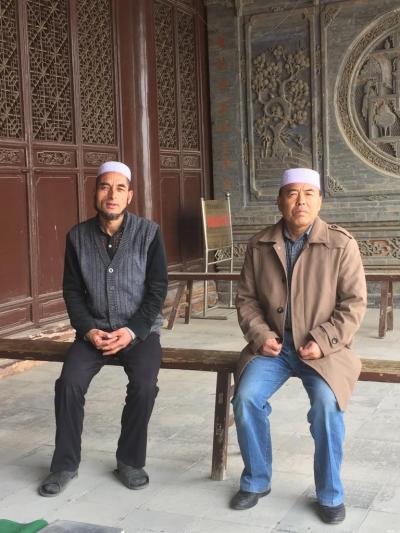

A few minutes later we tourists were outside putting our shoes back on and chatting with the attendant and a friend. They told me a few details about the enormous cemetery just outside the mosque, which I will get back to later.

Researching the Great Mosque online after I returned to Shanghai, I discovered that it once had been far from the only traditional mosque in Ningxia. However, most of the others were damaged or destroyed in the Cultural Revolution. The Great Mosque was spared thanks to its association with the Communist Revolution: The Red Army was active in the area from the 1930s on, and the mosque was the site of a meeting in which the Communists set up one of their first local political bodies in the country. This was enough to keep the mosque in one piece through the mid-century’s turmoil.