The Kumanovo district is one that has attracted a lot of attention from folklore ensembles lately, with mixed results when it comes to costume. The region is complex, with two distinct costume forms found locally among Serbian and Macedonian populations. Ethnic Bulgarian and Turkish populations dwindled but their influence remained as well. Moreover, the district experienced rapid changes in costume from the beginning of the twentieth century, something spurred by the preponderance of migrant work (pečalba, gurbet) among the men of the region; returning, they brought home new fabrics and western-style garments that were incorporated into, and eventually replaced, the folk costume. All of these things have led to a bizarre spectacle on the stages of Serbian folklore ensembles: costumes from wildly different time periods, side by side in the same choreography; multiple dancers wearing the heavy bridal headdress abandoned by WWI, even when not presenting wedding customs; and bizarre innovations borrowed from neighbouring regions and cultures. I hope that by sharing some of the costumes from my collection, I can at least sufficiently educate blog readers to spot these anomalies when they encounter them. Let’s make Kumanovo great again, people!

Named after Cumans, Kumani, a nomadic Turkic people who ended up in Eastern Europe and the Balkans having fled the Mongol invasion of their Eurasian Steppe homeland. Also called Polovtsi by the Slavs they encountered (from plav, a reference to their blonde hair and blue eyes) they settled primarily in Hungary and Bulgaria, two medieval kingdoms also with ancestral connections to Steppe Hunnic and Turkic tribes. They were everyone’s mercenaries, taking up the cause of any ruler with the right price. Hence, they found themselves in the medieval Serbian army of King Dragutin. The Bulgarian Кing Asen (also of Cuman ancestry) settled a large number of them in the plain between the Pčinja and Tabanovačka rivers, the site of today’s Kumanovo, or “city of Cumans”. The Cumans left no trace of their presence, being quickly assimilated by the majority Slavic population. Their presence is marked by toponyms ( kuman-, -kum, -kun) elsewhere: Kumane and Kumanica in Serbia, Comana and Comanesti in Romania, Kumanichevo (Lithia) in Greece, and Kiskunhalas and Kiskunmajsa in Hungary, to name a few.

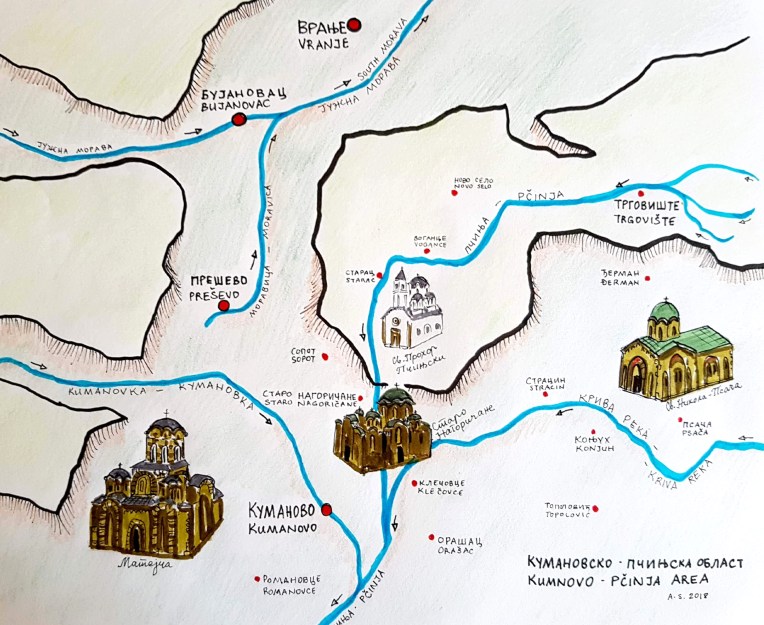

The main cultural centres for the Kumanovo Serbs were, for centuries, their monasteries. The most important of these were the church of St George in Staro Nagoričane, established by medieval Serbian King Milutin, and Matejča in the village of the same name, established by Serbian Emperor Dušan (whose capital was Skoplje) and his son, King Uroš “Nejaki” (the weak). Further afield but still of spiritual and historic importance was St. Prohor Pčinjski near Klenike. Founded by the 11th century Byzantine emperor Romanus Diogenes, the monastery played an important role in the rebellions that ensued as the nascent Principality, and soon after Kingdom, of Serbia drove the Ottoman Turks from this part of the Balkans bit by bit. Encouraged by the liberation of Niš, and the ongoing battle for the liberation of Vranje, the Kumanovo Uprising began. Led by notable Serbs of Kumanovo and surrounding villages, it was an uphill battle seeing the rebels fighting local Turkish and Albanian troops and spahis (feudal landowners) while staving off a Bulgaria eager to spread its propaganda and expand its territory. Backed by Russia, drooling over Bulgaria’s Black Sea ports, they used a perfidious system of sending teachers and clergy to spread a Bulgarian ethnic consciousness. The Turks and Albanians, obviously, did not have a stake in this goal, but certainly liked the idea of eliminating Serbs from the area. So, on two occasions the Serbs of not only Kumanovo, but of Skoplje, Tikveš, Kriva Palanka, Prilep and beyond, petitioned King Milan Obrenović for unification with Serbia. The rebels had successfully freed the immediate Kumanovo area, but after Russia and Turkey reached a peace the Ottoman army’s reprisals were horrific. The Turks banned the use of the ethnic identifier “Serb” and turned a blind eye to Bulgarian incursions while severely punishing any expression of Serbian identity or culture. Many Serbs migrated to the liberated Southern Morava valley. Those that remained saw their final liberation after the Battle of Kumanovo in 1912, during the Balkan Wars. A monument to the battle still stood on Zebrnjak hill but was destroyed by Bulgarians during WWII, thankfully leaving the mausoleum of those who died in battle.

The family and village slava were among the most important holidays for the villagers of this district. While family slave (pl.) tended toward winter saints (zimske slave), the village feast days were mainly in the springtime, often tied to the Paschal cycle: Ascension (Spasovdan), Holy Spirit Day (Duhovi), Holy Trinity Day (Trojice), and the universally celebrated St. George (Đurđevdan). Given that during the 18th century, the Turks demolished many village churches, villages without a church would rely on the local monasteries and clergy from these and neighbouring villages to conduct the religious portion of the slava rituals, most notably the festal procession (krstonoše) and blessing of bread. Villages in the area are mostly divided into mahale, male, or neighbourhoods – compact clusters of houses that are separated from one another over a larger area. Thus, the villages are a combination of compact and scattered. Older residents interviewed by Trifunoski explained the clustering or parts of a village, or entire villages, as a necessity to protect themselves from roving Albanian bands that would regularly raid and plunder Christian villages, with free rein from the Ottoman officials. Some of the entirely compact villages were, during Ottoman times, čifluk villages; that is, the residents were serfs of a local Turkish official, their aga. In his visits to villages, Trifunoski noted that some of the existing villages had ruins of medieval churches, or even of Roman buildings (Čelopek, Bajlovac, Kanarevo, etc.), attesting to the human presence here for centuries. Some of the villages could be traced to the Medieval Serbian Kingdom: Nagoričane, with King Milutin’s church of St. George, c. 1312; Dejlovce, mentioned in a document from 1381 where noblewoman Jevdokija (Eudochia) Dejanović and her son Konstantin made it a dependency of the monastery Hilandar on Mt. Athos. The same noblewoman endowed the village of Zubovce to the Russian Athonite monastery of St. Panteleimon in 1377. Naturally, Trifunoski recorded oral traditions that described the origins, settlement, and migrations of these villages, but one important source was the pomenik, or memorial book, at St. Prohor of Pčinja Monastery (Prohor Pčinjski). Orthodox churches keep the names of the deceased commemorated at Proskomidija or at Liturgy, and using the names of known clans or rodovi present in the Kumanovo district, he found mention of the residents of villages Algunja, Nagorićane, Klečovce, Čelopek, Orah, Karabičane, Skačkovce, and others. Finally, seeing as much of his field work here was done in the last few years before the Second World War, living memory and municipal records provided clear histories of the newest villages, founded by migration and colonization after WWI. Ljubodrag, Umin Dol, Tromeđa, and Rečica are among the “youngest” villages in the Kumanovo area.

The Serbs of Kumanovo basically share an extension of the material culture and folklore of the Upper Pčinja region. In modern terms, where we think of boundaries and borders, this may seem like the result of cross-border contact. But, when we take a closer look at the geography of the area, we see that it really represents part of a whole that experienced numerous internal migrations over the centuries. Of course, we can start with the river Pčinja itself, which forms from a series of converging streams in the Dukat mountains, gaining strength and size by a number of small tributaries, passing between Rujan and Kozjak mountains, past Kumanovo, down to Katlanovo where it merges with the Vardar River, draining into the Aegean. This is the only river originating in Serbia that belongs to the Aegean basin, and this is due to a tiny flatland known as the Kumanovo-Preševo divide (Kumanovsko-Preševska povija). Located at the midpoint of the Vranje valley and Kumanovo valley, it is the very spot where rivers to the north of it flow toward the Morava, Danube, and Black Sea; to the south, the Aegean. The povija may divide watersheds, but it connected populations of the Morava and Vardar valleys. The corridor of Vranje – Bujanovac – Preševo – Kumanovo was an important trade and migration route. It also allowed access to Skoplje, the Skopska Crna Gora and beyond. It made possible trade in fine goods from Thessaloniki northward, and of corn, wheat, and rice from the fertile Kumanovo plain. Migrations between villages in Izmornik (Vranje district), Gornja Pčinja (Trgovište and surroundings), and Kumanovo plain were well documented by one of the leading experts on the region, Jovan Trifunoski, in his extensive research. The connection is, to a certain degree, also reflected in costume influences, such as weaving techniques and designs for women’s aprons (skutače, skutine), styles of woollen vests (zubuni, klašenici), and embroidery motifs.

A great deal of what we know of the costumes of Kumanovo area can be ascribed to Hristifor Crnilović, a renaissance man of the early 20th century. Born in Vlasotince in southeastern Serbia, Crnilović served in the Serbian army during WWI, participating in the retreat across Albania to Corfu, and in the Salonic offensive. In the 1920’s he studied art in France (having studied in his youth briefly in Belgrade), but soon gave up art; the typhoid and malaria he suffered during the war left him with hand tremors that he could not overcome. He worked as a teacher in Skoplje, using every break to explore the region, documenting and collecting costume, jewellery and other material culture. We today are very fortunate for his decision to do so, as his collection is a true snapshot in time. He managed to preserve costumes, in pieces or in their entirety, that rapidly transformed or fell into disuse in the interwar period. This was a result of his guiding principle that the only true expression of traditional culture were found in “those which had not suffered the influence of industrial production”. Thus, he ended up with what one might call the purest or most authentic examples of Serbian textile culture of his time. His sisters, Leposava and Zora, collaborated in his research and protected his collection during the Bulgarian occupation of Skoplje during WWII. Today, the collection is housed in a museum affiliated with the Ethnographic Museum of Belgrade, called Manakova Kuća, itself a monument to a style of architecture long gone in Serbia.

Items collected by H. Crnilović, from Ethnographic Museum of Belgrade. (click to enlarge)

The folk costume of Kumanovo district varies to different degrees from village to village, but can be generally put into two groups that share comparable elements. One type is found in the eastern portion of the district, toward Kriva Reka, while another is clustered on the Kumanovo plain, the hills above the town, and towards the western Kumanovska Crna Gora. The latter is often referred to locally as “šopska nošnja” (Šop costume), due to its proximity to the Upper Pčinja. As much as some consider the term šop derogatory for highlanders, this is the term with which I was faced having interviewed people from the region and the term which I have chosen to use in order to simply distinguish the two variants. The Kriva Reka costume is the one more likely to be seen in men’s stage costumes of folklore ensembles, while they tend to use a mix of costumes for women.

Men’s summer costume from Stracin (From Kličkova et al, 1963)

The men of the district wear a summer costume which is almost entirely made of white linen or mixed cotton cloth, and a winter costume of brown woollen sukno. The costume parts are:

Potkošuljka – a light, hemp cloth undershirt

Nagušnjak – a false shirt front, or plastron, with embroidery or passementerie trims, worn between undershirt and shirt

Košulja – a heavier linen cloth shirt with embroidered collar, sleeves gathered at the cuff, and a broad lower portion or skirt, made wider by six to eight triangular inserts called rebrnjaci (ribs)

Pojas – wool or hemp cloth broad sash, woven with a black or dark bordeaux (“vinkav”) base and augmented with lighter coloured embroidery.

Gaće – loose fitting, light cotton trousers worn tucked into the socks.

Krpe – rectangular cloths, one decorative to be tucked into the sash; the other, a head covering decorated at the ends with crocheted needle lace

Čakšire – winter trousers, sewn out of brown sukno cloth to a fairly narrow fit

Jelek – brown sukno open vest, with little ornamentation other than along all hems and openings.

Gunjče – a sleeved short jacket worn in winter, also of brown sukno cloth.

Šubara – lambskin hat, worn in the winter throughout the region and in some villages to the north of the city of Kumanovo year round.

Čarape – knit from black wool and embroidered with geometric designs

Opanci – tanned or rawhide leather shoes with straps.

Ćustek – an ornament consisting of a closed rope of braided seed beads with a large circular pendant also made of seed beads, generally in geometric patterns. Can be worn around the neck, pinned to the jelek, or tucked into the pojas.

Women of Kumanovo district wear a costume that, like others in these regions, can get complicated with many layers of garments. The old bridal costume is incredibly complex, and includes a very tall and heavy headdress. The šop variant costume is simpler and lighter in comparison to both the Kriva Reka costume and those of neighbouring Upper Pčinja.

Garments that comprise the costumes worn by women in Kumanovo district include:

Košulja – hemp and cotton fabric shift, generally embroidered on hem and bodice, but much heavier on bridal costumes, with specific motifs such as dovrnjaci (sleeve hems), sekirčiki (“little axes”), kondirčiki (“little wine pitchers”), pruge (stripes), krškanica (broken, zig zag lines), devojke (maidens – stylized human figures). Floral motifs became common in the early 20th century.

Pojas, alov pojas – hemp cloth sash embroidered with multicoloured cotton and metallic threads, generally brown, black or red.

Zubun, Z’ban, Saja – an open vest, reaching down to the hips, sewn in three panels from lighter cotton or linen cloth and decorated with embroidery, appliques and sequins along the bottom of the panels.

Klašenik, ćurdija – a heavier open vest, slightly longer than the zubun, sewn from rolled wool cloth known as klašnja, decorated with čoja fabric appliques and chain stitch embroidery, occasionally augmented with sequins or metallic threads.

Skutača, skutina – woollen or hemp cloth apron, decorated with large floral or geometric elements (kola), often with metallic threads woven into the design. The hemp ones were generally woven in two pieces (pole) which were sewn together horizontally, while the wool ones were woven as a single panel.

Krpa, šamija – kerchief, either of ordinary cotton cloth (krpa) or of finer cloth, often industrially produced (šamija).

Čarape – multicoloured knit and embroidered socks, typically black, red, maroon or dark brown.

Opanci – either of tanned leather or rawhide, with straps

Đerdan – any number of silver niello or coin necklaces and bodice ornaments

Pafte – silver buckle worn with the sash.

Nevestinski fes – the bridal headdress, composed of a felt cap decorated with rows of silver coins, including a strap that went across the forehead (čelenka) and another below the chin to hold it in place. Dried, fresh and paper flowers were added to it, as well as feathers.

Bridal costume from Kumanovo district, Stracin village (Kličkova et al, 1963)

The pieces I have acquired from Kumanovo area have come from a number of collectors over many years. The klašenik came from a collector in Plovdiv, Bulgaria, who had acquired it in the village of Psača east of Kumanovo. Several zubuni and skutine aprons came from collectors in Niš, Belgrade, and Kruševac. I was fortunate enough to be able to purchase a complete woman’s costume, complete with pafte and a bridal cloth (peškir), from Anđelija Marinković of Belgrade. It belonged to her grandmother, who was originally from the village of Staro Nagoričane. I feel particularly fortunate that I have been able to acquire some truly elaborate skutače aprons; they are large and ornate, and all date to the turn of the twentieth century, if not earlier. My favourite is one from the village of Čelopek, the gift of my friend Nikola Stajković.

For Further Reading:

Bjeladinović-Jergić, Jasna. Bratislava Vukotić, Nikola Pantelić. (1986) Etnografska Spomen Zbirka Hristifora Crnilovića (The Ethnographic Memorial Collection of Hristifor Crnilović). (bilingual edition) Ethnographic Museum of Belgrade.

Kličkova, Vera. Anica Petruševa. (1963) Makedonski Narodni Nosii. Illustrated by Olga Benson and Marija Malahova. Ethnographic Museum of Skoplje.

Menković, Mirjana (2009) Zubun: Kolekcija Etnografskog Muzeja u Beogradu iz XIX i prve polovine XX veka. (Zubun: The collection of the Ethnographic Museum of Belgrade from XIX and first half of the XX centuries) (bilingual edition). Ethnographic Museum of Belgrade.

Trifunoski, Jovan F. (1974) Kumanovska Oblast: Seoska Naselja i Stanovništvo, Skoplje.

Trifunoski, Jovan F. (1951) Kumanovsko Preševska Crna Gora. Srpski Etnografski Zbornik, LXII, ser. Naselja i Porekla Stanovništva, knj. 38. Beograd.

Trifunoski, Jovan F. (1957) La Crna Gora de Kumanovo et Preševo. Bulletin de l’académie Serbe des Sciences tome XIX Série des Sciences Sociales No. 5. Belgrade.

Trifunoski, Jovan F. (1995) Makedoniziranje Južne Srbije. Cicero, Beograd.

Addendum: List of Serbian villages of Kumanovo district (from Trifunoski 1974)

Algunja, Petrovac, Čelopek, Nikuljane, Četirce, Karabičane, Sopot, Tabanovce, Gornje i Donje Konjare, Rečica, Ljubodrag, Novo Selo (named so as it was settled after WWI), Umin Dol (during WWII Bulgarians exiled its Serb inhabitants), Biljanovce, Tromeđa, Staro Nagoričane, (while Mlado Nagoričane Macedono-Bulgarian village), Dobrošane (with an Aromani, Cincar population as well), Strnovac, Dobrača, Žegnjane, Vračevce, Kojince, Karlovce, Pelince, Vragoturce, Malotino, Koćino, Ramno, Dejlovce (a dependency of Hilandar Monastery since 1321) Osiče, Željuvino, Bajlovce, Breško, Kanarevo, Orah, Strezovce, Ruđince, Pendać, Orašac, Pezovo, Kutlibeg, Murgaš, Jačince, Dovezence, Beljakovce