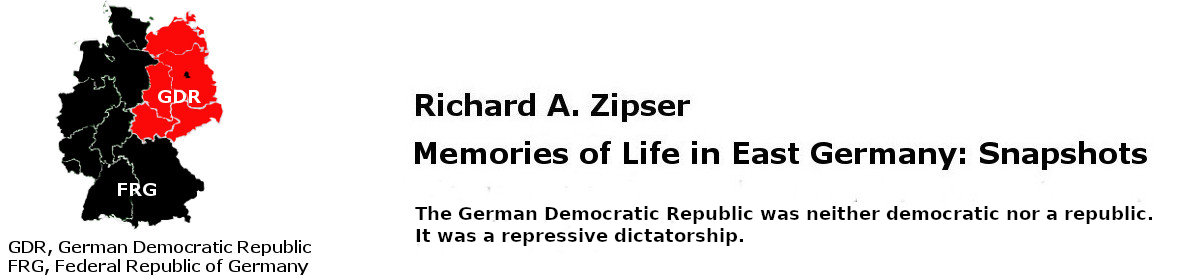

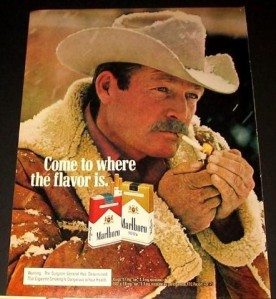

The “Marlboro Man,” iconic image for Marlboro cigarettes, 1970s.

In the summer of 1977, while vacationing on the island of Martha’s Vineyard, I bought a custom-fit “Country Marlboro Shearling Sheepskin Coat.” I did not smoke Marlboro cigarettes (or any other brand), nor was I eager to capture the spirit of the American West. I simply wanted to own a coat that would keep me warm in the frigid winter weather we typically had in northern Ohio, where the bone-chilling wind from Lake Erie would blow across the flat, prairie-like countryside. I was teaching at Oberlin College at that time and needed a coat I could wear every day during the winter. The handsome cognac-colored shearling sheepskin coat I found in a leatherworks store was just perfect for me. It had a substantial wind-cutting shearling collar and shearling lining that would hold out the weather and keep in the heat. Even in Oberlin, where the wind could drive snowflakes with the force of shotgun pellets, I would never be cold again!

On October 15, 1977, with the support of an IREX (International Research and Exchanges Board) grant I had been awarded in the spring of that year, I returned to East Berlin for a two-month period in order to continue work on a major book project. The project involved interviewing writers and gathering literary texts and other materials from them; hence, this stage of it had to be carried out in the GDR. Since my stay in East Berlin and work as an IREX scholar had the approval of the GDR Ministry of Higher Education and the sponsorship of the Humboldt University, I had a more elevated status than before. I was really excited about returning to East Germany and resuming work on the project that later became a three-volume book on GDR literature in the 1970s.

Packing clothes for this stay was somewhat problematic. I was limited to 44 pounds of luggage for the international flight, as I recall; for additional pounds I would have to pay a hefty penalty. I selected clothing items for my trip carefully, with a preference for casual wear. I knew that Berlin often has very cold weather in the late fall and winter, so I decided to take along my new shearling sheepskin coat. This I would carry onto the plane, along with my tote bag, and store it in an overhead bin. For rainy days, I decided to take along my London Fog raincoat, which I would wear onto the plane. Two overcoats for two months in East Berlin, that was all I needed. I could not have imagined the awkward wardrobe situation I would have to deal with when I reached my destination.

The Humboldt University provided me free of charge with a very modest studio apartment in a high-rise building in a neighborhood known then as the “Hans-Loch-Viertel.” It was situated in the locality of Friedrichsfelde and not very close to the center of East Berlin, “Berlin Mitte.” But the Friedrichsfelde subway station was nearby and I had wisely purchased an older Volkswagen in West Berlin, so I would not be wholly dependent on public transportation.

After I had gotten settled in the studio apartment, I began contacting writers in East Berlin and made appointments to visit them. I drove all over Berlin in my VW and also used the city railway. I did a lot of walking as well, especially when I was in Berlin Mitte and in the vicinity of the Alexanderplatz. In October I usually wore my lined trench coat while outdoors, but as the days became chillier I began wearing my beloved shearling sheepskin coat. I also wore blue jeans most of the time and brown leather boots. At this point I should mention that I had a full head of long brown hair, long sideburns, and a manly mustache (of the Burt Reynolds variety) on my upper lip. I had what one might call “the 1970s look.”

One day as I was strolling along Unter den Linden boulevard, heading toward the Alexanderplatz clad in the outfit described above, I noticed that passersby were staring at me. I thought to myself, what is going on? When a woman with her young son came walking toward me, I found out. As they were both looking at me, the young boy suddenly pointed his finger at me and said excitedly: “Look, it’s the Marlboro Man!” The Marlboro Man, indeed, even without the ubiquitous cigarette and cowboy hat. This was the beginning of something that caused me much embarrassment until I eventually got used to it. People everywhere would stare at the Marlboro Man from the US, even in the elevator in my apartment house; the adults would stare in silence, but young children would often point and exclaim: “The Marlboro Man!” There was no easy solution to this problem. In frigid East Berlin I had to keep wearing the warm cowboy coat, and I had to keep enduring the stares and exclamations whenever I was in public places. In retrospect, I am amused by this memory and pleased to have been an object of mistaken identity—not once, but time and again!

While writing this piece, I began to wonder how the East Berliners had become familiar with the Marlboro Man. Marlboro cigarettes were not sold in East German stores or vending machines, and naturally there were no ads for them on East German TV stations. But Marlboros were a popular brand in West Germany and commercials for them appeared frequently on West German TV stations. Most East Germans had access to a TV, but they were not permitted to watch West German stations. However, broadcasts from West Germany were of great interest to GDR citizens. There they could view the news of the day in an uncensored form and also watch other programs that interested them more than many of those GDR stations had to offer. They were especially interested in the West German commercials, according to a friend of mine who grew up in the GDR, and could all recite the lines and sing the melodies that went along with them. Hence, many East Germans pointed their TV antennas toward the West so they could receive the West German broadcasts, even though they were officially forbidden to do so. And that’s how they got to know the Marlboro Man who conjured up magical images of the Wild West of the US, the fascinating land of cowboys and Indians they had so eagerly read about in adventure novels by the renowned German author Karl May! Interestingly enough, Karl May had not visited the American West before or while he was writing books about it, so he and the East Germans had something in common.