A Talk with Jack Loeffler (Part 3): Soundscapes and Maps, Jack’s Toolkit, Nanao Sakaki, and the Heart of It

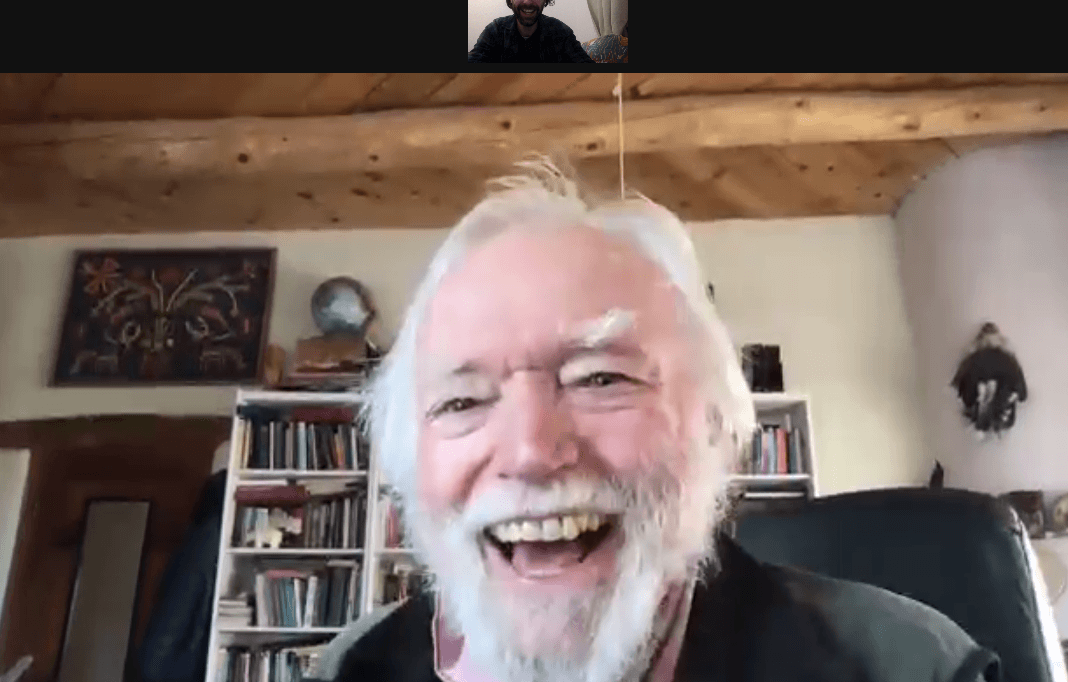

I had the good fortune to talk with Jack Loeffler over two days in December of 2021, and I transcribed the conversation. This is the third and final part of an edited version of our talk. (Read part one here and part two here).

RK (Rowan Kilduff) In your book, Headed into the Wind there was a part where you were presented with a drum–

JL (Jack Loeffler) That was with the Huicholes.

RK Do you still have it? When I read that part I was really wondering what was the message and the meaning of that, and how you felt about it?

JL (laughs) Well, it was (laughs) totally fundamental. I had an ax. We were camped near the village of San Andreas de Comyata and one of my tools was an ax, to chop dead firewood. (laughs) And the shaman that owned the drum, after the peyote fiesta wanted to swap the drum for my ax (laughs)

RK (laughs) OK, so –

JL So it was totally that kind of a thing, but I mean, he understood the spiritual significance of the drum.

RK And did you understand the spiritual significance of the ax? (laughs)

JL It was a tool, and anywhere I’ve gone whenever I’ve had tools with me, I’ve noted people looking at the tools and wondering how effective they were. And it’s sort of a reciprocal thing like when I moved in to the hogan at Navajo Mountain, that family who invited me to live in that hogan — that by the way was a male hogan which was shaped like a tipi, and the other hogans are more like inverted cupcakes, they’re different — that’s called the female hogan. And you don’t see them very often either, but you almost never see the male hogans anymore, that’s how long ago it was. But they loaned me a wood stove, up there at Navajo Mountain, and also a 30-gallon — it had been an ammunition carrying drum but it was such that I could carry it to a well and fill it with water, pump water into it and take it back to my hogan, and that’s what we lived on up there. But no, that drum, I still have it. My last job (laughs) — job job, for pay — ended in 1969 with that project where I was down in Mexico, the Huicholes, and I gathered Native American musical instruments from all across the United States, some of them were stored in a little guest house next door where our daughter stays when she comes with her family —

RK Do you have any water drums, the kind used for the peyote ceremony?

JL I used to. I don’t anymore. I passed that one along. I have my eagle bone whistle and I have my peyote rattle

RK Wow.

JL And I have my eagle feather, and I have my stick. But it’s been, I think 1969 or 70 was the last time I took peyote, and it was in a tipi, and it was near Santa Fe. It was outside Santa Fe in the country, and I had long realised that I was better at taking it by myself — being out in the countryside, alone, than being in a tipi — but I did it occasionally in a tipi. And a funny story here, in that particular peyote meeting, Baba Ram Das was there and he was shaking the rattle a little too vigorously and the head flew off. (laughs)

RK (laughs)

JL And he was mortified (big laugh). He was a good man, I really liked him. I knew him for quite a while, pretty well, but anyway, back in the day. But the upshot is that I have these Native American musical instruments and I’m considering donating the entire collection, there are maybe sixty or seventy of ‘em.

(Talking about The Gulch in Durango, Colorado)

JL I know that you’re a mountain-runner.

RK I try to be.

JL One of the writers is a trail runner, Morgan Sjogren, and they put out beautiful stuff… (RK: about Jack’s upcoming essay in The Gulch on the Colorado River Compact) it’s an essay in what not to do! It’s kind of a long essay.

RK And have you planned some other radio shows or books?

JL Well I’m compiling an anthology, normally I publish with the University of New Mexico Press and I’ve done all together as I think of it – 9 and a half books (laughs)…

And all of my radio series are based on my own interviews in person, face-to-face with people. And I haven’t been on the road now, well, since the COVID epidemic started, and I’m not sure I will again. But I have a lot of material, and it’s not an impossible idea to do more radio. I’ve done a lot of radio, about 400 programmes all together.

RK Yeah, what I really appreciate very much is how you recorded so many soundscapes.

JL Ah yes, so that to me, is part of it —

RK Some ecologists are using soundscapes quite a lot to gauge how wildlife is returning or disappearing just by studying these sounds of birds and animals. And that’s really interesting for me.

JL I started doing that back in the mid-1990’s. I’d gotten a grant to do a radio series basically focusing on the relationship of indigenous Indians with their respective habitats in the North American West. So, I travelled throughout the West, which was a long, long trip — thousands and thousands of miles — camping in my pickup truck and recording people, but also I tried to record as many habitats in stereo as I could so that, not only could I hear the individual species but I could –

it was to me a key to understanding interspecies communication between different birds and whatever, et cetera, and I’m really glad I did that and it’s maybe the best. What I’d like to record if anything, is wildlife.

RK And this can provide a very special alternative mapping of bioregions and different habitats, just by the sound. I don’t know if somebody has compiled these soundscapes into a digital map but that sounds super interesting.

JL Well at one point that’s what I wanted to do, but as you know, the American West, west of the 100th meridian, is a huge area!

JL And you know the map that John Wesley Powell made of the watersheds of the west?

RK Well, I know Dave Foreman’s maps from back in the days of Earth First!

JL Well, it came to me that John Wesley Powell was the first guy that ran the Grand Canyon and they did it in wooden dories and… it’s a great map. He did that map in around 1889-90. And William deBuys and Gary Snyder… the three of us concur that he was the first true bioregional thinker and one of the great pillars of environmental thinking in the United States, he and Thoreau… gee whizz, mental block!

RK John Muir.

JL John Muir. And Aldo Leopold, finally, you know, a century later. And then it was picked up by people like Dave Brower and Martin Litton, and then when Ed Abbey published Desert Solitaire in 1968, that really kicked off the radical aspect of it big time. But this map, I’ve travelled through all of those watersheds and I’ve recorded aspects of each one of them as well as some of the indigenous peoples in all of them, and — wow!

RK And would you like to see that done one day, from the soundscapes you’ve recorded, that a map would be done. Or it would be used for some science, or citizen science project?

JL It took me, what, several months to do the whole radio series. But to really do it right, would take… you know, some years. And at age 85 that ain’t somethin’ I got (laughs)

RK (laughs)

JL And actually I was even offered a grant to do it.

RK Yeah?

JL Do you record much?

RK Just music, in the studio with the band for a few years. But nothing like soundscapes.

JL I travel with a really good recorder because a lot of my recordings have become CDs. I’ve recorded a lot of chamber music for CDs and symphony orchestras as well as folk music. I just recorded one, it was probably my last one. But I’ve always done it on location with the best microphones I could use and the best recorders I could use. Stereo portable recorders that work on batteries that last for quite a while — that would be ideal for this kind of work.

RK Yeah.

JL (Talking about John Wesley Powell’s map that he has framed at home) Boy, it’s terrific. I look at it everyday because I look at watersheds and bioregions almost as intermingled. I mean, there may be twenty bioregions in a given watershed if you look at it one way. But the watershed consciousness, that I think Nanao Sakaki shared with a lot of people, was deeply right on the mark: that a land area could be looked at geographically from the point of view of watersheds rather than legislated boundaries like we have here in the west which just signify nothing but linear thinking and trying to get political stuff through — that’s the wrong way to go. That’s why my daughter and I did that book, Thinking Like a Watershed, because if it starts at the grassroots level, to me, and people start to decentralise their consciousness out of the prevailing institutional / religious / political boundaries, we might get somewhere. And starting at the grassroots is the most peaceful way. So, there. (laughs)

RK So how close are we to really get over those borders in thinking – that we could look at a bioregion or watershed? And related to Nanao Sakaki, was he influenced somehow by the shinto way of looking at ‘spirit places’ — the kami realms of the bear in the mountain and the river having its life-force, and that can be a spiritual way of thinking of a bioregion, but practical also. And what are your thoughts about this kind of worldview, if you have some experience, or did you talk to Nanao about this?

JL Well, I don’t know too much, but one time I was in Japan, I was working with a film crew and we went to the 38th anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima, and that was a very profound moment. Well, there were 110,000 Japanese there in what’s known as Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima, and then the four of us, known as gaijin — that’s what the Japanese call —

RK The westerners.

JL Non-Japanese.

RK Mm-hmm, yeah.

JL And I wondered how they were going to react to us, but they reacted to us in beauty, really.

RK Yeah, yeah.

JL But the upshot is, is that the night before, we’d gone, in the dark, to the park just to sense it and feel it and everything. And people were lighting candles and putting them in boats and floating them down the river, one for each person who was killed by the bomb. And it was… I recorded the music that came from that, there was accompanying music which is very wonderful, but that was truly one of the most profound moments I’ve ever had. With regard to Nanao, I can’t speak for him, John Brandi knew him better than I, and so did Gary (Snyder), but I know he was deeply attuned to the spirit of place, and you can just see that — or could see that — in his features and the way when we’d go for a walk or something, the way he related to place, it was unlike the way most people do. And that’s something I could ask John Brandi.

RK Can you share some of your experience with him (Nanao), or travels with him… because I can’t get to know except through his writing which I read and re-read — he’s still quite alive in what he left behind, a kind of bright trail.

JL One of my best memories of Nanao, it had to have been about 35 years ago, he was staying with us here in our own place, the one that we built with our own hands, and Nanao spent much of the morning just hanging out with our five year old daughter. And one of the things that just tickled her to death was when he leaned over and just stood on his head and keep talking to her at the same time.

RK (laughs)

JL In other words, he was like the epitome of zen (big laugh), and he — I don’t know but, Nanao lived at Gary’s place, off and on, quite a while, and then Gary got Allen Ginsberg together with him. I guess, in a way Nanao, to me, is the great beat poet of Japan and… but he was a wilderness person, I mean, he could handle cities, but he was at home in the out-of-doors and the natural world, and he walked watersheds consciously thinking of them as watersheds and that, to me, was a kind of a profound thought. In other words, he and John Wesley Powell would’ve had some really great conversations.

RK It feels like he inspired so much by the place where you live, a lot of his poems, or maybe all of them based in North America, are desert songs and walks through the desert.

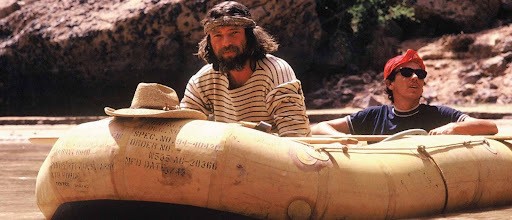

JL I’ll tell you one adventure we had that was really interesting to me: Nanao loved to watch birds, and about oh, 150 miles south of here is one of the most amazing wildlife refuges I know in North America where I’ve seen as many as ten thousand sandhill cranes all at the same time, I mean, it’s an extraordinary thing to behold. And so, I knew that Nanao would really get off on this, and so I took him down to this wildlife refuge. And in the early evening, before dark, but at dusk, is when the sandhill cranes would come in and they’d land in the water, say, about a foot and a half to two feet deep in order to protect themselves from coyotes and other mammals that might attack ‘em. And they started coming in, in big groups of twenty, thirty birds in a V-formation and landing in the water. And Nanao (laughs) stood there transfixed for a good hour and a half without moving one inch in any direction — totally tuned in to those cranes, and he thereafter wrote his Noh play about cranes, based on that experience (RK: ”Crane Dance”, in the books Real Play and Let’s Eat Stars). It was, I mean, his concentration… It was amazing! I enjoyed watching Nanao as much as I did watching the cranes. (laughs)

RK (laughs) And was he a really talkative guy? I’ve read so many things about him. Gary Lawless, up in Maine, published his books and he compiled a book called Nanao or Never, do you have it?

JL No, I don’t, but I’ll have to get it.

RK I don’t know why you’re not in it, because it’s a collection of writing about him from people who knew him, and this book shows a picture of him that’s at times, totally into the party and talking and having a wild time with everybody and having fun, and at other times meditating long times on his own in the wilderness, very peaceful, maybe talking with the kids and spending a lot of time with children, as you said.

JL Well, he did, I mean like — he and my daughter, my daughter remembers him very well, and I really liked Nanao. There are not too many people left who knew him but Nanao, he loved the South-west, he lived in a tipi, off and on, up on Lama Mountain, north of Taos, which is where the Lama Foundation is. That was founded in 1967, I think, by Steve and Barbora Durkey, and one of the great countercultural places in New Mexico — it continues to endure, which is amazing — and he lived there, even in the winter-time, he’d live in a tipi, he could be comfortable in just about any condition. As a matter of fact, Gary Snyder told me that when he died was standing outside taking a leak before dawn, and fell over dead.

RK He went out maybe to watch the stars.

JL Yeah. Well, he was an amazing fellow human, and I didn’t know him as well as I’d have liked to. I knew him well enough that we had some fun. After that event, by the way, driving back north, he had a lady friend with him at that time, the three of us went to a poetry reading by another really old and dear friend of mine — a man who’s no longer with us named Drummond Hadley, who was a cowboy-poet, and a good one, boy, who had a ranch down on the border with Mexico, and (laughs) Nanao sat there and watched Drummond carry on. I think, as I recall, Drummond — who always drank a bit of Glenfiddich scotch before he got deeply into anything — took out his pistol and shot a hole in the ceiling or something and Nanao got… (laughs)

By the way, he was also a close friend of Gary Snyder. And one week, Gary and Carole — his last wife, Carole Koda, who was also a very dear friend of mine — we spent a week at Drummond’s house, in the ranch, right on the border with Mexico and it was a great week we had. I recorded Gary there and Drummond talking about ranching as an endangered practice, and public land ranching, to me, has serious flaws in it because a lot of those guys really didn’t treat the land well, some of them did — I’ve actually documented a very important rancher who’s now in his nineties who’s here in New Mexico, who’s done a terrific job of getting ranchers to think in a different way. And Drummond certainly did, Drum Hadley. He died about five or six years ago. But Nanao got such a kick out of Drummond, I mean, I could see he would just sit, lean back and forth with his grin on his face, and nod, you know, and he’d clap his hands together and it was beautiful. He was an interesting guy, very interesting and I liked him a lot.

RK And Jack, do you know if Nanao is well-celebrated in Japan? Or well remembered? Or was he very alternative and the counterculture… I don’t know if it’s gotten into the mainstream (in Japan) even now.

JL That’s a good question. I suspect he is, in a limited fashion.

RK Mm-hmm.

JL I mean, have you ever been to Japan?

RK Yeah, twice on very short visits. Once close to Nagasaki, and once on an island in between Japan and Korea where I was living for a couple of years.

JL Boy, that’s really great.

RK Yeah, but at that time I didn’t know about Nanao yet so I didn’t search into this, but I thought of it sometimes, even as a poet publishing in the English language I feel like maybe more people could know about him in these times.

JL Well I think more could here too. To me, he was probably as close to the perfect bioregionalist as existed. At least the way I knew Nanao.

RK Yeah.

JL And when I knew him, when I first met him and throughout the time that we knew each other, I was kind of a hardcore environmentalist in those days, and… how to put it? I didn’t have quite the restraint (big laugh) but, and this is something that Gary and I have talked about a lot, there’s something – an intrinsic quality to the whole business of being into the environmental perspective and in an active way that invigorates just about every sense that a human being can possibly have, I mean, it really does.

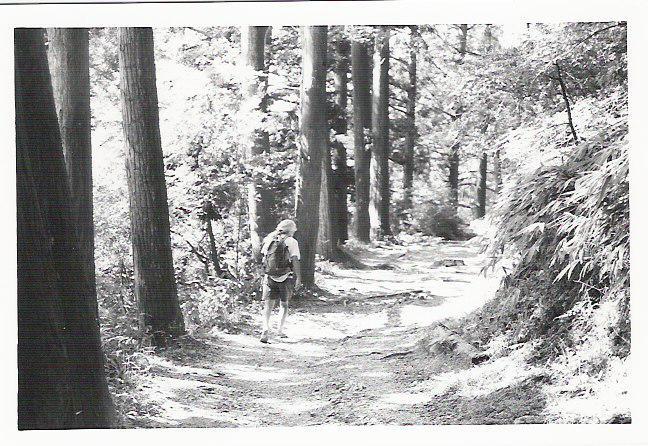

(top) Nanao. Photo overlay & acrylic. 3 non-haikus. RK ; (below) Nanao on the ridge trail up Atago-san, west peak of Kyoto, in flip-flops. Photo by Ken Rodgers

(Kyoto Journal)

JL I’m still, actually, as a result of our conversation yesterday, re-thinking this essay I’m writing on direct action — because it’s a new… the guy who wrote the book about blowing up the pipeline in Sweden, I don’t think he’s as new to the notions that direct action can invigorate, which I think if it’s done in the sabotage way, and this is something that Ed Abbey and I talked about deeply, it can really invigorate more of a police state. To take out a D-10 caterpillar somewhere doesn’t help the movement at all.

RK Yeah.

JL In other words, violence begets violence. And this is something that is really necessary to think about. As far as I know, Nanao never invigorated any sense of violence whatsoever. That wasn’t his way. He was of the nature of the place, and that’s the way I saw him. And boy, I don’t know, I’ve been very fortunate in the people I’ve gotten to know over the course of my lifetime, because some of them political people… for whom I rarely have respect, but I know a couple of politicians that I do like — one of whom is dead, and the other is his son who isn’t dead. (big laugh)

RK It’s extraordinary, the people you’ve met, the friends you’ve made. Maybe some people have also been connected together because of you and your work. To go back to maps, what role do you think songs, and songs as stories, songs as a kind of map-making through life or through a country or region… What role do songs play in this? I’m thinking of songs from the indigenous worldview but also newer poetry, art, stories.

JL Well, to me it’s vital. In other words, that can be as close to the heart of it — boy!

JL About music, I have a good pal here, he lives about 6 miles (from here), he and I used to play jazz. He’s one of our great ethnomusicologists in America, his name is Steve Feld, and he lived for a year down in New Guinea, recording – he’s got the same recording equipment as I do, we got it about the same time, that original equipment we got back in the 70’s. The people he lived with, who were deeply traditional, not yet effected back then in the 70’s when he was doing his field work, by monoculture. He told me their language is based on birdsong and weeping, wow…just think about that. He’s done incredible films too. To me, he’s probably the epitome of what a true ethnomusicologist is but not only that – he’s a great jazz player, we used to play a lot together back in the day. We had a lotta fun playing it too. Actually he’s been trying to get me back on a horn. (laughs)

”deepspace Nanao”

a NASA deep space field photo; Nanao Sakaki (1992, Ken Rodgers); ‘red bird’ cutout-painting: RK

RK What do you think about nuclear weapons in these times? Do you get worried that we’re not being more actively against nuclear weapons and maybe a lot of people (from my generation and younger) don’t think about it much and think that this is already solved somehow. I know Nanao was a really big activist in this and a lot of his writing goes in this direction.

JL Well he actually was a radar man for the Japanese, and he saw the plane with the bomb. And I told him that I’d seen bombs go off at the Nevada proving ground from seven miles away, that was one of our conversations, I’ll tell you!

RK Yeah, I bet.

JL But I feel that we’re still in mortal danger from that because I feel that the military mentality is very exclusively linear, and does not in any way see the bigger picture. From the window I’m looking at it right due north-west, 40 or 50 miles from here – and I can see it on a clear day – is Los Alamos where the atom bomb was first constructed, and when I look to the south-west I see San Dia peak and the Monsano mountains which traditionally have been the largest storage for atomic bombs in America… and I’ve actually visited the Trinity site where the first atomic bomb was detonated. I’ve thought about atomic bombs big-time for a very long time. One time Terry Tempest Williams and I discovered that we’d been at either end of the atomic bomb that I had played music for, and it blew us both away. To me the most profound thing that happens, having seen the bombs go off, is that they exclude nothing – the habitat itself is rendered deadly for a long time to come.

RK And there’s no border to this. This blast radius includes the sky, the air, it travels around the planet. It includes everybody and last for a pretty long while.

JL Yes, it does. As a matter of fact, at one point – I have it somewhere – Ed Abbey gave me a map where the air currents had carried many of the bombs that had been detonated at the Nevada proving grounds, and what worries me is the state of mind of people who are so institutionalised in their thinking that they’re… it’s like they’re in jail within a system of attitudes within which they cannot escape nor do they want to. And that, to me, is what is so spooky about today. They were thinking that because it was in the desert that it wouldn’t hurt anything, but the amount of life in even a desert is huge.

RK Yeah.

JL And it took it all, and gee whiz, I mean, that was to me the beginning of the imminence of total environmental disaster that humankind could visit on the planet. And we’ve now followed up with all of these others.

RK Mm-hmm.

JL And I still feel that the big work needs to work on attitude, cultural attitudes. A very long time ago when I was having a peyote moment, this was still in Marin County, north of San Francisco on the side of Mt. Tamalpais, where I lived, I saw that it was the most important thing I could do was to pull all of the nails out of my frame of reference. And that has stayed with me, to try to incorporate everything into a sphere of reference where I can see the interrelationships between all of the things that pass through my mind. And what I just wonder is, I mean, we’re equipped with our five senses plus our intellect and our intuition and our emotions and that, well, what sense is – there are certain things that could happen that other senses could pick up on, I’m sure. I’ll back up a step here, institutional thinking especially occurs here in our schooling systems and our educational systems, and then in our institutional systems even at the university level, in many cases, and at the church level in just about all cases, as far as I’m concerned… Frames of reference are constructed that are virtually inescapable, and people who are caught up in those institutional frames of reference – they get ever smaller as we become ever more divided. That is what has to be addressed. And the model for addressing it is looking at habitat, and wild habitat is the best way, from my point of view. That’s where you get your bearings. But any habitat – the interaction between species within a habitat is one of the most important things to become deeply, deeply, deeply aware of – because that’s one way out of this dilemma of cultural attitudes that are just almost unbreakable. And that in conjunction with the ever-growing numbers of people, that’s just, I mean, we’re in such dire straits right now. I don’t know how we’ll wend our way out of it, but working with young people – I wish I could do it in person, but right now we’re under strict COVID stuff here.

RK Here too.

JL I mean, I may be 85 but man, I’m still 20!

RK Nanao’s poem – ”Break the Mirror”, the title poem from the book – he sees himself as 17, is it? Howling with coyotes, singing against nuclear war, young, charming man – he still feels it all the time. ‘To stay young, to save the world, break the mirror’

JL Yeah. Absolutely!

RK The way to save the world is to stay young.

JL One time with Gary Snyder, we had several really important adventures together. At one point Gary and I started travelling together throughout California interviewing some of his old beatnik friends to get their perspectives down, but one of the things that was revealed during that was that he had made a vow, the day after Hiroshima, to be – I think that was the day he climbed Mt. St. Helens, which is a pretty good sized mountain in northern California the same day as we bombed Hiroshima – and that had a huge effect on Gary’s thinking, and I know Gary and Nanao had a huge effect on each other’s thinking. When Gary met Nanao he was so blown away and Nanao had a profound effect on a lot of people here, in a big way.¨

(note: Gary Synder has said this of Nanao, ”he’s in the tradition, which is a tricky tradition in East Asia, of the eccentric, rogue, radical, wandering poet. And usually, they don’t think very well of such poets until two or three centuries have gone by at least”)

RK Did you ever record him?

JL No, I never did. I did with John (Brandi) and I did (with Gary). In 2017 I co-curated an exhibition on the history of counterculture.One of the things that I did then was I went back to Gary’s house at Kitkitdizze, which is an Indian word which means ‘kitkitdizze.’ (laughs)

RK (laughs) It’s a plant, right?

JL I’m not sure. I’m not sure. But I recorded Gary reading his ”Four Changes.” Which is one of the most beautiful things I’ve ever recorded. He was in his 80’s at that point, and so was I for that matter – geez! (laughs) And, I mean Gary and I’ve spent a lot of time together, and after he finished reading the last word, he looked at me and he said ‘Boy, were we idealistic.‘ And that was so poignant to me, and I said, ‘Man, we still are!’ (big laugh)

That’s actually… on the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, Gary Nabhan came up with the idea of trying to get Gary Snyder involved and so what we did, with Gary’s permission, is we used that entire recording I did of him reading that and Bioneers (which is a pretty good outfit here in this country) put it up on the web. (RK: It is available from Bioneers on SoundCloud.)

My recorder runs out of space and so we talk for a good hour more ‘off-the-record’ about Gary Snyder and myth-making; John Brandi’s paintings, and how Jack’s now reading all of his books; more about nuclear war; about the Nevada sky, his lookout in the truck under the sky; Margaret Mead smoking hash; Navajo language; and did you know that Seri language is its own phylum? Where did they come from? Jack says to me, ‘someones got to go down and record their songs about where they came from’; I ask him what’s a life well-lived, and he answers that it’s how we just do our best. Jack notes the definition of ‘sabotage’, and that the thing about Ed was that he was a total egalitarian, and against anything that creates more divisiveness (so) Jack almost blew up a pipeline. Did he regret not doing it sometimes? About Black Mesa and the aquifer; how to rethink ‘peace’ to ‘mutual co-operation’; that all the guys he knew back when they were just guys…

We talked about Dune, Hayduke!, the Whole Earth Catalog, the Earthrise photo & Stewart Brand, about what might be the next ‘Earthrise’… what could the next thing be that brings about a collective change in awareness? The multiverse, answers Jack. He says, between two infinities ‘is where we dance’, where it’s real, where it’s at; about Muscle Shoals, playing Moanin’; and about Baba Ram Dass after a bad trip and Jack nursing him for a week to get back to reality (‘what a beautiful man’); Carlos Castaneda, peyote and all the things that we can’t write about, the sacred; Jack told me how he recorded so many Native American songs, but to be accessed only by members of that tribe / Nation; about speaking from a place beyond words or where words do not reach (‘it’s hard!’); and we talk a lot more about activism; Jack said, ‘I never had a teacher, wilderness nature is my teacher, these four deserts…’

We tell more stories, about Jack’s 60-day lookout posts, and I told him about when I spent all summer under the stars, eyes snapping open, hard to fall asleep, and then with eyes closed still seeing stars (‘wow’).

to Jack Loeffler

firmament shot with

honed consciousness

we see how

we are blind sided

to what’s kindred.

clear! always

the great sky

including everything

including everyone.

part of

made of

in the arms of

the wind.

About Nanao Sakaki:

Nanao Sakaki was a poet, counterculturalist thinker, activist, Nature-lover, free man…

Gary Snyder writes of him in the introduction to Break the Mirror: ”His poems were not written by hand or head, but with feet…You can put these poems in your shoes and walk a thousand miles!”

His activism included walks for the Yoshino river, protesting Monju nuclear power plant and ‘singing against nuclear war’; calling for the protection of virgin forests, the Shiraho Blue Coral Reef, and Hokkaido (Moshiri, The Peaceful Land) against ‘kamikaze projects’; he called for the independence of Okinawans, and celebrated the Ainu (the indigenous people of the Japanese archipelago, or mythic Yaponesia), Native Americans, and Aboriginal indigenous peoples. Nanao said that what we need is transformation, not revolution. Legend tells that he walked North America many times, lived in a tipi, and said that the desert was his teacher. When asked if he belonged to any buddhist group he replied, ‘whitewater!’

By Nanao: Break the Mirror (includes Real Play), Let’s Eat Stars, How to Live on Planet Earth, Inch by Inch: 45 haiku by Issa (his own translations and in his handwriting), Bellyfulls; and there is a book about Nanao called Nanao or Never (from Blackberry Books).

John Brandi says:

…we were camped in a slickrock canyon when a young man stirring the coals asked Nanao, How does one get by in a world as distracting and demanding as ours? Nanao laced his boots, put a few dried plums into his knapsack, and looked up: “What is fundamental is to live cheaply in a tasty way.”

Audio of him reading Break the Mirror at Seibu Kodo event Nov. 3, 1988, sent to me by Ken Rodgers:

About Jack Loeffler:

Jack Loeffler is an aural historian, environmentalist, writer, radio producer, and sound-collage artist. His Navajo friend, Shonto Begay writes, “by documenting the voices and stories of the land Jack moves us and helps us to rediscover our own voices.” Jack’s daughter says, “He makes friends everywhere he goes, because he cares. He empathizes and connects with every living being he encounters. From the child sitting across from him at a restaurant to the Navajo elder, and the great horned owl to the spiny cholla cactus, he cares about it all.” He was a founder of the Black Mesa Defence Fund.

By Jack Loeffler:

Headed Into the Wind: A Memoir; Survival Along the Continental Divide: An Anthology of Interviews; Voices of Counterculture in the Southwest; Adventures with Ed; La música de los viejitos: Hispano Folk Music of the Río Grande del Norte; Healing the West: Voices of Culture and Habitat; Headed Upstream, Interviews With Iconoclasts; Thinking Like a Watershed: Voices from the West; & a lot of radio shows (about 400). He has recorded 3-4,000 folk songs and his recordings of indigenous peoples, songs, stories, and interviews with many activists, musicians, and the places themselves as soundscapes are now available from the Smithsonian and at the Museum of New Mexico.

Rowan Kilduff is a dad, mountain-runner, and activist-artist. He writes on the connection between ecological and world peace; wilderness, urban wildlife, and forests, and he is the author of a few books, as well as various articles that appear in print and online. He lives in Central Europe, currently up and down between 49 and 52°N.