Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome

A rare, fatal, genetic condition of childhood with striking features resembling premature aging

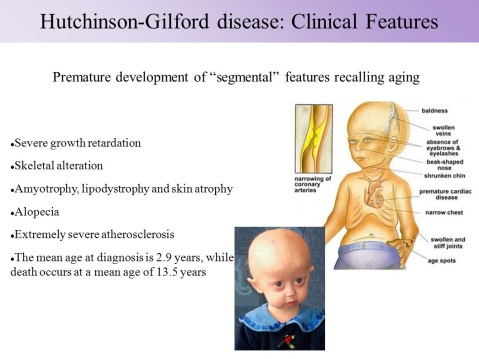

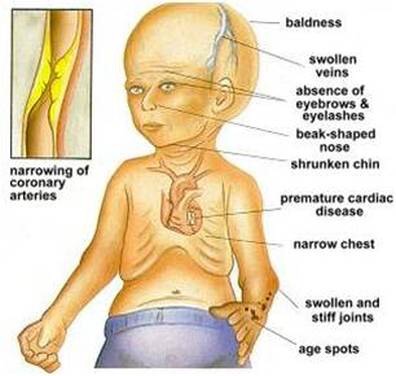

Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome is a genetic condition characterized by the dramatic, rapid appearance of aging beginning in childhood. Affected children typically look normal at birth and in early infancy, but then grow more slowly than other children and do not gain weight at the expected rate (failure to thrive). They develop a characteristic facial appearance including prominent eyes, a thin nose with a beaked tip, thin lips, a small chin, and protruding ears. Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome also causes hair loss (alopecia), aged-looking skin, joint abnormalities, and a loss of fat under the skin (subcutaneous fat). This condition does not affect intellectual development or the development of motor skills

Etiology:

Mutations in the LMNA gene cause Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome. The LMNA gene provides instructions for making a protein called lamin A. This protein plays an important role in determining the shape of the nucleus within cells. It is an essential scaffolding (supporting) component of the nuclear envelope, which is the membrane that surrounds the nucleus. Mutations that cause Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome result in the production of an abnormal version of the lamin A protein. The altered protein makes the nuclear envelope unstable and progressively damages the nucleus, making cells more likely to die prematurely.

Signs and symptoms

Newborns with HGPS may have certain suspicious findings present at birth, such as unusually taut, shiny, hardened (i.e., “scleroderma-like”) skin over the buttocks, upper legs, and lower abdomen; bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membranes within the mid-portion of the face (midfacial cyanosis); and/or a “sculptured” nose.

Profound, progressive growth retardation usually becomes evident by approximately 24 months

By the second year of life, there is also underdevelopment (hypoplasia) of the facial bones and the lower jaw (micrognathia). The face appears disproportionately small in comparison to the head, and bones of the front and the sides of the skull (cranium) are unusually prominent (frontal and parietal bossing). Affected children typically have additional, characteristic facial features, including a small, thin, potentially pointed nose; unusually prominent eyes; small ears with absent lobes; and thin lips. Dental abnormalities may also be present, such as delayed eruption of the primary (deciduous) and secondary (permanent) teeth; irregularly formed, small, discolored, and/or absent teeth; and/or an unusually increased incidence of tooth decay (dental caries). In addition, abnormal smallness of the jaw may result in dental crowding.

In children with the disorder, the scalp hair becomes sparse and is typically lost (alopecia) by approximately two years of age. Scalp hair may be replaced by fine, downy, white or blond hairs that, in some cases, may persist throughout life. In addition, the eyebrows and eyelashes may also be lost during early childhood.

HGPS is also characterized by distinctive skin abnormalities. As discussed above, newborns with the disorder may have “scleroderma-like” skin changes over the buttocks, thighs, and lower abdomen. In addition, beginning in infancy, there is a gradual, almost complete loss of the layer of fat beneath the skin (subcutaneous adipose tissue), and veins in certain areas of the body, particularly over the scalp and thighs, become abnormally prominent. In affected children, the skin acquires an abnormally aged appearance with areas that are unusually thin, dry, and wrinkled and/or unusually shiny and taut. In addition, brownish skin blotches may tend to develop with increasing age over sun-exposed areas of the skin. Affected children also typically have defects of the nails, such as fingernails and toenails that are yellowish, thin, brittle, curved, and/or absent.

Children with HGPS also have distinctive skeletal defects. These may include delayed closure of the “soft spot” at the front of the skull (anterior fontanelle), an abnormally thin “dome-like” portion of the skull (calvaria), and/or absence of certain air-filled cavities within the skull that open into the nose (paranasal or frontal sinuses). In many cases, affected children also have short, thin collarbones (clavicles); narrow shoulders; thin ribs; and a narrow or “pear-shaped” chest (pyriform thorax) with a prominent abdomen. In addition, the long bones of the arms and legs may appear unusually thin and fragile and be prone to fractures, particularly the bones of the upper arms (humeri).

In many children with HGPS skeletal abnormalities include degenerative changes (osteolysis) that may affect the collarbones (clavicles); bones of the ends of the fingers (terminal phalanges), causing the fingers to appear unusually short and “tapered”; and/or the hip socket (acetabulum). Degenerative changes of the hip socket may result in a hip deformity in which there is an abnormal increase in the angle of the thigh bone (coxa valga), hip pain, and hip dislocation. In addition, in many affected children, abnormal fibrous tissue progressively forms around certain joints (periarticular fibrosis), such as those of the hands, feet, knees, elbows, and spine, causing unusual prominence, stiffness, and limited movement of affected joints. Due to stiffness of the knees, progressive hip deformity (coxa valga), and other associated musculoskeletal abnormalities, children with the disorder tend to have a characteristic, widely based, “horse-riding stance” and a shuffling manner of walking (gait). The disorder is also associated with generalized loss of bone density (osteoporosis), a condition that may cause or contribute to repeated fractures following minor trauma.

Additional symptoms and findings may also be associated with HGPS. These may include a distinctive, high-pitched voice; absence of the breast or nipple; absence of sexual maturation; hearing impairment; and/or other abnormalities.

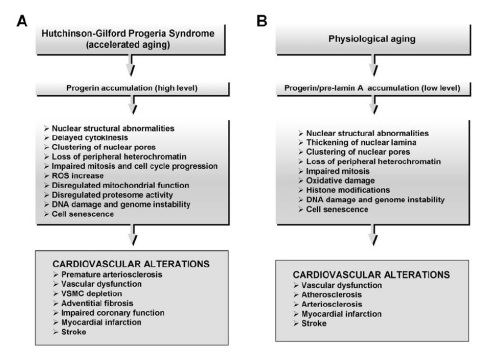

According to reports in the medical literature, affected children as young as five years may develop widespread thickening and loss of elasticity of artery walls (arteriosclerosis). Such changes may be most evident in particular blood vessels, such as the arteries that transport oxygen-rich blood to heart muscle (coronary arteries) and the major artery of the body (aorta).

Additional findings may include enlargement of the heart (cardiomegaly) and abnormal heart sounds (i.e., as heard during a physician’s examination with a stethoscope) due to altered blood flow through valves or chambers of the heart (cardiac murmurs). During childhood or adolescence, progressive arteriosclerosis may lead to episodes of chest pain due to deficient oxygen supply to heart muscle (anginal attacks); obstructed blood flow within blood vessels of the brain (cerebrovascular occlusion); progressive inability of the heart to effectively pump blood to the lungs and the rest of the body (heart failure); and/or localized loss of heart muscle caused by interruption of its blood supply (myocardial infarction or heart attack). In individuals with HGPS progressive arteriosclerosis and associated cardiovascular abnormalities may result in potentially life-threatening complications during childhood, adolescence, or young adulthood.

Diagnosis:

HGPS is usually diagnosed during the second year of life or later, when progeroid features begin to be noticeable. The diagnosis is based upon a thorough clinical evaluation, characteristic physical findings, a careful patient history, and diagnostic genetic testing, which is available through The Progeria Research Foundation (www.progeriaresearch.org ). More rarely, the disorder may be suspected at birth based upon recognition of certain suspicious findings (e.g., “scleroderma-like” skin over the buttocks, thighs, lower abdomen; midfacial cyanosis; “sculptured” nose).

Specialized imaging tests may be conducted to confirm or characterize certain skeletal abnormalities potentially associated with the disorder, such as degenerative changes (osteolysis) of certain bones of the fingers (terminal phalanges) and/or the hip socket (acetabulum). In addition, thorough cardiac evaluations and ongoing monitoring may also be performed (e.g., clinical examinations, X-ray studies, specialized cardiac tests) to assess associated cardiovascular abnormalities and determine appropriate disease management.

Treatment and management:

Lonafarnib, a type of farnesyltransferase inhibitor (FTI) originally developed to treat cancer, was shown to be effective for progeria. Every child showed improvement in one or more of four ways: gaining additional weight, better hearing, improved bone structure and/or, most importantly, increased flexibility of blood vessels.

Other than lonafarnib, which is not FDA-approved and thus only available through clinical drug trials, the treatment of HGPS is directed toward the specific symptoms that are apparent in each individual.

Symptom management and palliative care: promote quality of life.

Incidence and genetic counselling:

Progeria is not usually passed down in families. The gene change is almost always a chance occurrence that is extremely rare. Children with other types of progeroid syndromes which are not HGPS may have diseases that are passed down in families. However, HGPS is due to a sporadic autosomal dominant mutation – sporadic because it is a new change in that family, and dominant because only one copy of the gene needs to be changed in order to have the syndrome. For parents who have never had a child with progeria, the chances of having a child with progeria are 1 in 4 – 8 million. But for parents who have already had a child with progeria, the chances of it happening again to those parents is much higher – about 2-3%. This is due to a condition called mosaicism, where a parent has the genetic mutation for progeria in a small proportion of their cells, but does not have progeria

Sources:

https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/hutchinson-gilford-progeria/

https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/hutchinson-gilford-progeria-syndrome#definition