We’ve been conducting field surveys of regal fritillary butterflies for the last three years. During that time, we’ve learned a lot about how those butterflies are responding our prairie management and restoration work. So far, there are two overwhelming lessons we’ve learned from our work.

1. The number of regal fritillaries produced in our Platte River Prairies is primarily tied to two factors: violets and thatch. During the spring, when adults are first emerging from their chrysalises, butterfly abundance is highest in degraded remnant (unplowed) prairies that have few showy native wildflower species, but lots of common blue violets (Viola sororia). While they don’t have much to excite a prairie botanist, these prairies sure produce a lot of regal fritillaries. We don’t find many regals in recently burned portions of these prairies – only in portions that have built up some thatch.

2. After regals emerge and mate in those thatchy violet-rich prairies, they spread out into more flowery sites to feed. In our Platte River Prairies, those feeding sites tend to be restored (reconstructed) prairies located around and between those degraded remnants. Those restored prairies have significantly fewer violets than remnant prairies, but lots of the favorite nectar flowers for regals, including hoary vervain (Verbena stricta), milkweeds (Asclepias spp.), wild bergamot (Monarda fistulosa), and thistles (Cirsium and Carduus spp.). Interestingly, while we don’t see regals emerging from recently burned prairie, some of the most-used summer nectaring sites are our most recently burned sites.

You can see more details of these findings in a summary I posted last year after our 2011 field season. Our 2012 data didn’t contradict either of these two major lessons, but did show the impacts of the very warm and dry weather we had this year. The first of those was that butterflies emerged several weeks earlier than in 2010 and 2011. This year’s highest counts were in mid-to-late June instead of mid July. In addition, in 2012 we saw almost no regal fritillary butterflies after about July 10. In 2010 and 2011, we saw only a few here and there during their reproductive diapause period of late summer, but then saw slightly more in early fall as females reactivated themselves and started laying eggs. This year, we didn’t see any evidence of egg laying at all – which might make next year an interesting one!

This year’s unusual weather and corresponding butterfly data makes comparisons of habitat use between recent years tricky. However, one pattern we can examine is the way butterfly production shifts from place to place in response to our management activities. Most of our degraded remnant prairies have abundant violets, so the numbers of emerging adult fritillaries seems to be driven primarily by how much thatch is present.

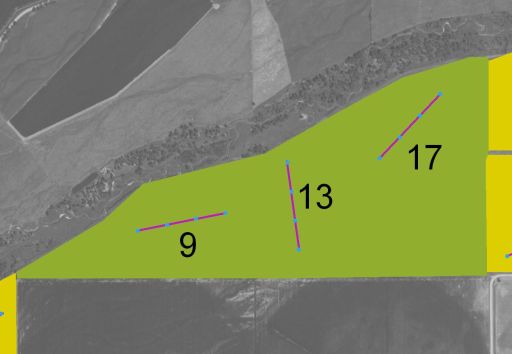

Below is an example of a prairie that showcases the way regal fritillary production is impacted by our management. This prairie is managed with patch-burn grazing, so a portion of the prairie is burned each year, and cattle focus their grazing primarily in those burned patches, allowing older burned patches to recover. This creates a shifting mosaic of habitat structure, and regal fritillaries respond just as you would predict.

Butterfly transect numbers 9, 13, and 17 in a 175 acre degraded remnant prairie along the Central Platte River in Nebraska. Each transect is 300 meters long.

.

Highest Weekly Counts of Fritillaries by Transect

Transect # 2011 2012 Last Fire

9 2 19 2011 (grazed hard)

13 26 1 2012 (grazed hard)

17 34 31 2010 (light-moderate grazing)

.

In the above table, you can see the peak number of regal fritillaries along each of three transects during 2011 and 2012. In both years, the highest counts came in the early part of the season (late June – early July) when adult females were emerging and mating with males. Because this mating occurs in the same area from which the butterflies emerged, we can use these data to see where production was highest. The red numbers show counts that took place on transects that had been recently burned, so very little thatch was present and those areas were being grazed intensively by cattle. The third transect (#17) was burned in 2010, but our stocking rate was low that year and the burned patch was not grazed as hard that season as is typical – perhaps helping explaining the high numbers of butterflies seen the following years. However, transect # 9 was burned and grazed hard in 2011 but still had fairly high numbers of regal fritillaries the next year. That is consistent with what we’ve seen in other prairies as well – even a little thatch can produce regals, though more seems to be better.

Conservation Implications

There has been a lot of discussion among butterfly biologists about the impacts of prescribed fire on rare prairie butterflies. Fire has been blamed (at least in part) for causing or speeding the disappearance of rare butterfly species from some small tallgrass prairies. As a result, a few biologists have become leery of using fire at all when rare butterflies are present. That, of course, creates conflicts with prairie managers who see prescribed fire as an important tool to maintain the viability of other species and processes within the prairie community. As I’ve discussed before, there are no easy answers to that conflict, but the problem is more related to prairie size than it is to fire.

What we’re seeing in our Platte River Prairies seems to indicate that butterflies like the regal fritillary can thrive in landscapes where prairies are (relatively) abundant and prescribed fire is only applied to a subset of that prairie habitat each year. When we conduct spring fires, we certainly kill a large number of regal fritillary larvae that had been overwintering in the thatchy vegetation. However, we apparently have enough unburned prairie nearby that the butterfly populations can absorb those losses. Prescribed fire has been a common management activity for at least 25 years on land owned by Platte River conservation organizations, and regal fritillaries remain one of the most abundant butterfly species here.

We don’t yet understand all the reasons some prairie butterflies are disappearing across the tallgrass prairie. However, it’s no surprise that it’s difficult to maintain populations of species in tiny fragments of habitat. Clearly, burning an entire isolated prairie in one fell swoop can be devastating to vulnerable insect populations (and other species), but that doesn’t mean that prescribed fire is not ever compatible with the survival of rare insects. The long term prognosis is poor for many species in small isolated prairies, regardless of how those prairies are managed. We can argue all we want about how best to manage those doomed habitats, but let’s be sure we’re also spending time figuring out how to make those prairies bigger and more viable. Then, we can worry less about individual species and just manage for prairie communities.

Our butterfly work has been largely funded by State Wildlife Grant funding from the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Surveys were conducted by Mardell Jasnowski and a variety of technicians and volunteers under her supervision.

– Thank you!

Nice work. How do proposed patch burn schedules (usually 3 y rotations) with grazing fit into your notion about how this works? We need to get together soon and talk about this.

Hi Tony,

Thanks. I think a 3 year fire frequency is probably ok for butterflies. If you were trying to optimize butterflies, of course, you’d set something up based on only that. Hopefully, people who are using patch-burn grazing for something other than research are more plastic in their implementation than a set 3 year (or whatever) rotation. And, hopefully, patch-burn grazing is being set up to achieve broader objectives than just production of a single species!

Happy to talk anytime. The guy who is best suited to talk about patch-burning and butterflies, though, is Ray Moranz – Iowa State University. I can share what I’ve learned, and what I think, though. Call or email!

Chris,

Do you have any research on some of the rare prairie skippers, and what can be done to help them? As for the Platte Prairie regals, I understand they are quite abundant. While that isn’t the case in some of the southeastern Nebraska prairie remnants, or am I mistaken?

Dan, we’ve looked, but haven’t found any other really rare prairie butterflies our sites (yet?) so I don’t have any data. I also don’t know much about the status of regals in SE Nebraska, except that people from the area don’t seem to talk about them as rare. From what I understand, they’re a common species – I just don’t know any relative abundance numbers for context.

Nice to know that V. sororia will support his butterfly. It seems virtually any violet will do for a larval food plant, but that there are, perhaps, local preferences.

Reblogged this on Lep Log.

Pingback: Lessons From a Project to Improve Prairie Quality – Part 1: Patch-Burn Grazing, Plant Diversity, and Butterflies | The Prairie Ecologist

Just re-reading this post as I revisit questions I am mulling over regarding butterflies and fire. It brought to mind a question I’ve been thinking a lot about lately. Do butterflies benefit plants? Perhaps this is a trivial question, but I’ve found that it is sometimes worth re-examining conventional wisdom and “established fact.” Most of the dialogue I have with colleagues regarding butterfly/plant interactions seem to be all one way, i.e., what do the butterflies get from various host and nectar plants. I’ve started thinking about this from the other perspective, i.e., what might the plants be getting out of visits from butterflies (or their larvae)? It seems to be widely stated in the literature that “butterflies” act as “pollinators,” but I haven’t been able to turn up any studies where this is specifically looked at. Maybe this was demonstrated so thoroughly so long ago that no one studies it anymore, so it doesn’t show up in searches of the more recent literature? Based on your experience and observations, have you bumped into any obvious evidence of butterflies acting as pollinators, or perhaps more subtle benefits conferred by the presence of grazing larvae? Or perhaps you can just point me to few studies that answered this definitively years ago.

Pingback: Regal Surprises JZ | Winged Beauty Butterflies

There was worried reference to a lack of regal ovipositing flights in this post. Did the regals come back in 2013? Or since?

Ryan, they did come back, though their numbers throughout the Platte Valley (not just on our properties) seem to still be lower now than prior to the severe 2012 drought year. We continue to do annual monitoring to track them.