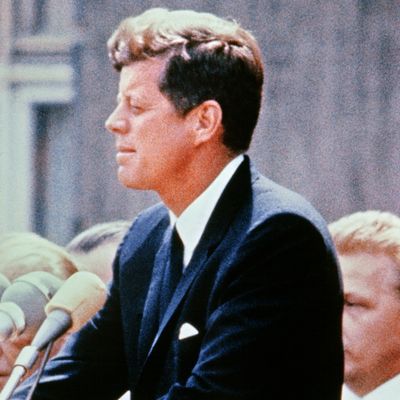

If you’re wondering what to make of the assassination of John F. Kennedy in light of the National Archives’ not-quite-final release of government documents related to the case, start with this: Lee Harvey Oswald was a loser with a lot to prove.

Oswald himself was murdered before the country got to know him as anything more than a smirk, and conspiracy theories buried the details of his personal life almost immediately afterward. But by the age of 13, he was already “turning around the topics of omnipotence and power … to compensate for his present shortcomings and frustrations,” according to a report written by the chief psychiatrist at Youth House, a New York detention facility where Oswald spent six weeks in 1953. At 17, he joined the Marines, but was court-martialed twice, once for accidentally shooting himself with a handgun, and another time for fighting. Oswald picked up Marxism, taught himself Russian, and defected to the Soviet Union in 1959, slashing his wrists in Moscow when it appeared he might not be able to stay. But after less than three years of working a lathe in Minsk, he returned to the U.S. He drifted from job to job, and from Dallas back to his hometown of New Orleans, where he got into a street fight and a catastrophic radio debate with anti-Castro Cuban exiles, then back to Dallas. There he tried to murder former Army General Edwin Walker, a prominent anticommunist and segregationist, by shooting a rifle into Walker’s home. He missed.

In an era before weaponized young loners seemed like a type, Oswald, by November 1963, was an anxiety-ridden 24-year-old who loathed America and had failed at essentially everything he tried. His one great stroke of luck came when newspapers announced that President Kennedy’s motorcade would pass the schoolbook depository building where Oswald had just begun working.

The newly released documents do nothing to alter the basic ballistics findings of all four government investigations into what happened at Dealey Plaza when Oswald finally made his mark: His Mannlicher-Carcano rifle fired three shots, two of which hit Kennedy from behind, and one of which killed the president. Nor do the papers establish that Oswald was working for the Soviet or Cuban governments, or for anybody. In fact, they reveal that the Russians recognized him as unstable. The KGB concluded Oswald wasn’t worthy of being an intelligence agent for either the Americans or the Soviets, and was happy to let him return to the U.S. And a reliable source for the FBI, who was in the U.S.S.R. when Kennedy was killed, said that “Soviet officials claim that Lee Harvey Oswald had no connection whatsoever with the Soviet Union,” according to a memo the Bureau sent to the Johnson White House in December 1966, but which wasn’t declassified until Thursday. “They described him as a neurotic maniac who was disloyal to his country and everything else. They noted that Oswald never belonged to any organization in the Soviet Union and was never given Soviet citizenship.”

The new papers do add to the case for a cover-up, but it’s a different cover-up than buffs brought up on Oliver Stone’s batshit-crazy JFK are looking for: It’s not a plot to kill Kennedy that government officials have spent the past 54 years hiding, it’s all kinds of other dirty pool. Their own incompetence, for one. The FBI, CIA, and other agencies had 124 pages of pre-assassination files on Oswald — naturally enough, since he had moved back and forth between the U.S. and Soviet Union — but new papers show they lost track of him after November 8, 1963.

Shady surveillance, for another. The CIA knew because of wiretaps that Oswald contacted the Cuban and Russian embassies in Mexico City in September and October 1963, looking for a visa to return to the Soviet Union. Oswald also wrote a letter to the Soviet embassy in Washington, “which we interrupted, read and resealed,” FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover told President Johnson two days after Kennedy’s murder. “To have that drawn into a public hearing would muddy the waters internationally,” Hoover continued. “To use all that would reveal our failure to carry out international courtesy laws.” The government sat on its info — making Oswald’s movements appear much more mysterious to anyone trying to investigate the assassination than they probably were.

Most critically, any examination of Kennedy’s death threatened to expose American plots to overthrow foreign leaders, such as Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic, Fidel Castro in Cuba, and Ngo Dinh Diem in South Vietnam. So the CIA offered nothing about U.S. assassination attempts to the Warren Commission, and Kennedy administration officials continued to stonewall congressional investigators a dozen years later. (Former Defense Secretary Robert McNamara testified in 1975 about plans to kill Castro: “I do not believe that President Kennedy gave the authority. I also do not believe that the CIA would take such action without the authority. I know that is contradictory but that is the way it is.”)

The new releases, however, add shocking detail to the story of just how far U.S. officials were willing to go to get rid of the Castro regime — a lot farther than trying to deliver exploding cigars to Castro himself. For example, a January 19, 1962, memo from Gen. Edward Landsdale, who ran the Kennedy administration’s “Operation Mongoose” efforts against Castro, asked the Pentagon to “submit a plan … to put a majority of workers out of action, unable to work in the cane fields and sugar mills, for a significant period … consider non-lethal BW [biological warfare], insect-borne, introduced secretly to the target area by the Navy.”

If covert action couldn’t cripple Cuba’s farm workers, officials in Washington were ready to cripple its farms: On September 6, 1962, the group overseeing Mongoose considered “agricultural sabotage … specifically the possibility of producing crop failures by the introduction of biological agents which would appear to be of natural origin.” McGeorge Bundy, JFK’s national-security adviser, said he had no worries about such a plan, but that “we must avoid external activities such as release of chemicals, etc., unless they could be completely covered up.”

Meanwhile, a Defense Department report from August 8, 1962, envisaged invading Cuba. This week’s declassifications lifted long-blacked-out details: The Pentagon said 261,000 military personnel could seize control of “key strategic areas” on the island within ten-to-15 days. “There may be a requirement for amphibious lift for rapid deployment and counterguerilla activity until order has been restored,” the memo says with a straight face.

These are just a few of the kind of proposals that floated around the highest levels of the American government in the early 1960s. Many turned into action; the new releases document, across thousands of pages, how the U.S. provided support for attacks by Cuban exiles. And training for those exiles and military plans for an invasion continued into 1963, well after the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Details about all this are still trickling out to the American public, but they certainly made an impression on Castro, and maybe on Oswald, too. When an Associated Press correspondent named Daniel Harker met the Cuban prime minister on September 7, 1963, Castro heatedly denounced the American raids, saying: “U.S. leaders should think that if they are aiding terrorist plans to eliminate Cuban leaders, they themselves will not be safe.”

That threat didn’t appear in the New York Times or Washington Post, but the interview did run in the New Orleans Times-Picayune, Oswald’s local paper — and Oswald was an avid reader. A 1975 CIA memo found that neither the Warren Commission nor the CIA had looked into the possibility of blowback, but that somebody should have. Castro’s warning, it argued, “must be considered of great significance in the light of the pathological evolution of Oswald’s passive/aggressive makeup after his attempt to kill General Walker … and his identification with Fidel Castro and the Cuban revolution.” That statement itself, however, was kept classified for another 42 years.

Secrecy breeds secrecy, though not always in the sense we expect. The real conspiracies of the assassination aren’t about who killed JFK or how. They began in the moments after his murder and have yet to untangle completely, because they’re about what the instruments of American power were up to while Kennedy was president.