- India

- International

Guns and Roses: Osho’s disciples recall their days in the wild, wild country

Controversial spiritual leader Osho’s disciples, those who followed him from Koregaon, Pune, to Oregon, US, recall their days in the wild, wild country and why the the godman held such sway over them.

In their own world: Oshoites during a dance meditation at the centre in Pune. (Express photo by Arul Horizon)

In their own world: Oshoites during a dance meditation at the centre in Pune. (Express photo by Arul Horizon)

The imposing gates of the Osho meditation resort in Pune’s Koregoan Park area open to reveal an idyll: landscaped gardens, pathways lined by bamboo trees, peacocks strutting on grass and sanyasis in maroon robes walking around desultorily. Suddenly, the calm scatters as London thumakda rings out from speakers at the Buddha Grove. It is time for the “dance celebration”. With wild abandon, the sanyasis and visitors begin to move, oblivious to all else around them. The euphoria is palpable; it has not been deflated by Wild Wild Country, a Netflix documentary on the commune that has gone viral across the world. “We live in our own heaven here. They don’t know what’s happening outside, nor are they bothered,” says Ma Sadhana, spokesperson for the Osho International Resort, Pune.

These scenes stand in sharp contrast to the ones from the riveting six-part documentary. The images that remain in your mind after you have watched it are of gun-toting sanyasis, of the deliberate poisoning of Oregon restaurants by Osho disciples, and the battle that raged between the inmates of Rajneeshpuram and the residents of Antelope, some miles from the Big Muddy Ranch in Oregon, where Osho and his disciples had arrived in 1981 and spent the next four years building the commune.

It was in March 1974 that the Rajneesh ashram was established in Pune. For the next seven years, it continued to both intrigue and scandalise the conservative residents of a so-called “pensioners’ paradise”. Those were the days of free love, as professed by Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, and amply demonstrated by the commune residents. Rajneesh’s evening discourses, too, were punctuated with jokes, many of them lewd.

As the numbers at the commune grew swiftly, with foreigners outnumbering Indians, so did the opposition to its bohemian lifestyle. The criticism hardly made a difference till an attempt was made on Rajneesh’s life on March 22, 1980, by a member of a radical Hindu outfit. Ma Anand Sheela, a trusted aide of Rajneesh, was entrusted with the task of finding a new location for the commune. She decided on Oregon. On June 1, 1981, after his last satsang, Rajneesh swept out of the commune with a convoy of five cars that drove up to the Jumbo Jet at Pune airport and flew to the US — the entire upper deck of 40 seats had been reserved for him.

The movement now started on its next, and, perhaps, most controversial phase. A posse of crimson-robed sanyasis trooped into the 64,000-acre Big Muddy Ranch at Wasco County, Oregon, which had been bought by Sheela for $ 5.75 million. All sanyasis were allotted tasks, from constructing homes to setting up the kitchen. “Routine is not a word I use for living and working in our commune. There was never a dull moment! The work assigned to one could change at the drop of a hat. We were learning new skills and honing our awareness and focus. One of my assignments was being a taxi driver, transporting small goods all over the property. The other, and one I did for the longest, was being a ‘Twinkie’ — working in press relations at the visitors’ centre,” says Ma Bhagawati aka Eveline Morriss, a 70-year-old British citizen, who now lives in Bali.

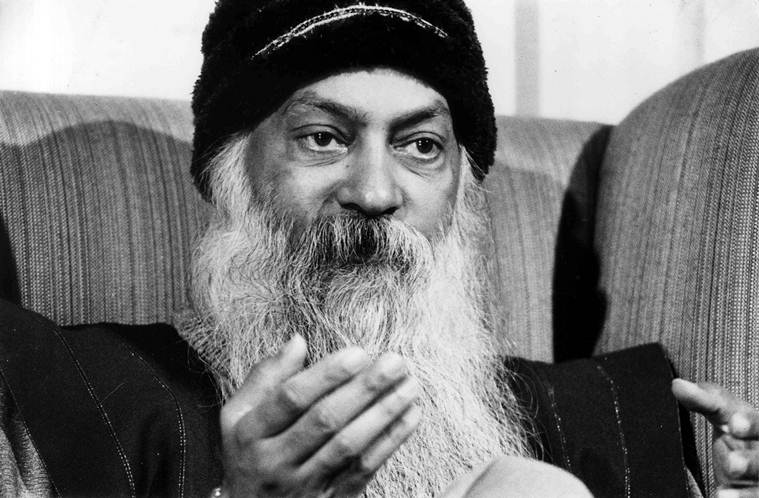

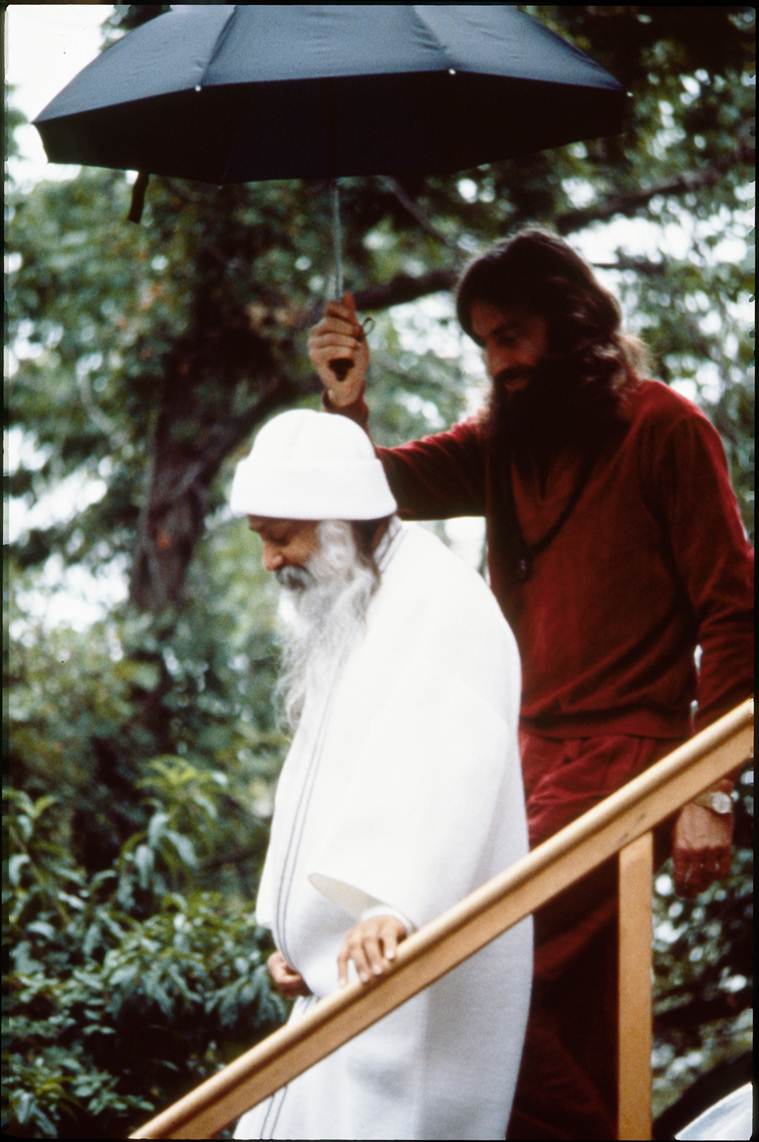

In October 1984, Osho ended three-and-a-half years of self-imposed silence, which had started when he reached the US, with discourses with a “chosen few”. (Express archive photo)

In October 1984, Osho ended three-and-a-half years of self-imposed silence, which had started when he reached the US, with discourses with a “chosen few”. (Express archive photo)

She was drawn into the world of Osho because of a vision. It was 1976. “While living in Germany at the time, I was meditating, with my eyes closed. Suddenly, I saw Osho looking straight at me. I had only seen a photo of him on a book cover before. In that moment, I felt something like lightning travel through my body. I knew I had to meet this man. I wrote to him. The response was a letter from Pune, with a new name that Osho had given me. Six weeks later, I flew to Pune,” she says. When the commune packed up from Koregaon, she followed Rajneesh to Oregon. In an era before internet, Rajneesh had made a name for himself through his books, audio tapes, and his discourses.

“In the early days, when I reached Rajneeshpuram, there were approximately 50 people there,” says Swami Chaitanya Keerti or Narain Das, former spokesperson of the ashram in Pune and now editor of the Osho World published from New Delhi. Keerti spent two years in Oregon and then left for Europe in 1983, only to return to Oregon in December 1984. “My work was to set up houses for new people,” he says.

a few months later, his job changed. He would travel daily to the city of Antelope, where a dispatch department for Osho books and tapes had been set up. “We did not have licence to sell the stuff at the ranch. I also had the job of responding to letters from India and informing Osho lovers about what was happening in the new commune,” he says. Keerti’s highlight of the day was seeing Osho come out for a daily drive from Rajneeshpuram. “When he drove by, we would welcome him by singing and dancing,” says Keerti, who now lives in Delhi’s Oshodham, a group that broke away from the Pune commune.

In October 1984, Osho ended three-and-a-half years of self-imposed silence, which had started when he reached the US, with discourses with a “chosen few”.

The commune had grown in leaps and bounds. It had its own fire and police departments, a school, a shopping mall, a bookshop (that sold only Osho’s books) and an airstrip. With more affluence, came greater hostility from the residents of Antelope. Margaret Hill, the mayor of Antelope which had a total population of 40, was “paranoid,” says Keerti. Hill started lobbying government agencies to remove the ashram from Oregon.

When a militant bombed Hotel Rajneesh in Portland in 1983, the commune — often referred to as a cult by the Americans — armed itself to the teeth, acquiring over 100 semiautomatic rifles, which was more than what the entire Oregon police force possessed — and a huge cache of ammunition. At the helm of the change was Ma Anand Sheela nee Sheela Ambalal Patel. Sheela, who was born in Baroda, had moved to the US for higher studies at 18. She and her husband joined Rajneesh when they moved to India in 1972 to pursue spiritual studies. After her husband passed away, Sheela devoted herself to life in the commune.

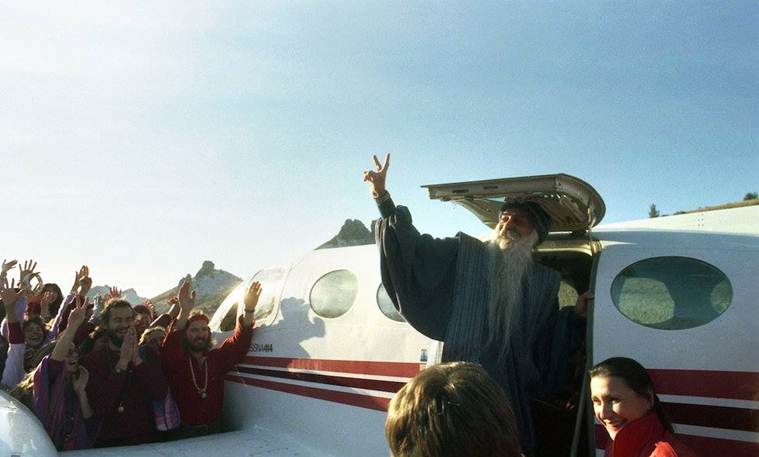

Follow the leader: Disciples wave Osho goodbye as he leaves Rajneeshpuram.

Follow the leader: Disciples wave Osho goodbye as he leaves Rajneeshpuram.

Sheela became Osho’s secretary in 1980 and soon held near-absolute sway over Rajneeshpuram. Sheela was the only one who met and “spoke” to Rajneesh every evening and conveyed his message to the disciples.

In the face of growing opposition from Antelope’s residents, who were scandalised by a commune of free love in their midst, and as a result of Rajneesh’s silence, the commune rallied around Sheela, “someone who was not just efficient, but also fiercely protective of us,” says Keerti. Sheela armed the sanyasis, but also dragged the commune into murky terrain. The ranch, including Osho’s rooms, was bugged; homeless people who had been brought into the ashram were drugged; she nearly engineered a mass food poisoning attempt at Antelope that took 751 people ill; and even planned the stabbing of Osho’s physician Swami Prem Amrito.

At the Osho resort in Pune, Amrito, one of the most important figures in the documentary and in Osho’s life, recalls the dark days in Rajneeshpuram. The British doctor was Osho’s physician in Oregon and Pune; he was present when he passed away on January 19, 1990. In one of the many shocking episodes in the film, he is stabbed by Sheela’s close associate, Ma Shanti Bhadra, with an adrenaline-filled syringe, allegedly at the behest of Ma Sheela, who was intensely jealous of Amrito’s growing closeness to Osho.

Amrito is dismissive of his portrayal in the documentary. “Show business is show business!” he replies nonchalantly. He remembers the stabbing vividly. “They had made an attempt the year before, so I was not as shocked as I might have been!” he says. Amrito spent four years at Rajneeshpuram from 1981 to ’84, formative years for the movement in the US. He was dogged by controversy after Osho’s death for not signing his death certificate and changing his identity from Dr George Meredith to Dr John Andrews to Swami Devaraj to Amrito.

Ma Bhagawati aka Eveline Morriss, author of Past the Point of No Return (2010), also spent four years at the Big Muddy Ranch. “I arrived in Oregon in 1982 and got busy building the commune with the others. But the pressures of Oregon residents and various politicians eventually forced us to establish the Rajneeshpuram Peace Force. The arms came much later,” she says. Bhagawati admits that she did not like to see sanyasis carrying weapons. “I felt uneasy that this was considered necessary for Osho’s protection. But I remember pushing away the uncomfortable feelings and concentrating on what Osho had to say,” says the 70-year-old now settled in Bali.

“Remember not one shot was fired, not one person killed,” says Swami Satya Vedant, a former Berkeley professor and former chancellor of Osho Multiversity in Pune. Vedant was in Oregon almost throughout Rajneesh’s stay. “I was one of those who guarded the place at night and would see people coming in pickups with guns. Arming ourselves was nothing but self-defence,” he says.

His most cherished memory at Oregon is of loading groups of homeless from New York city in Greyhound buses and getting them to the ashram to offer them a more “respectful and dignified life”. That they were also potential voters who could sway the local elections in favour of the residents of Rajneeshpuram was just a beneficial fallout, he says.

Osho with his physician and trusted aide Amrito.

Osho with his physician and trusted aide Amrito.

While views regarding the documentary vary, the sanyasis are near-unanimous in their condemnation of Ma Sheela. “Power corrupts and absolute power corrupts absolutely. This film showed the tragic story of Ma Anand Sheela and her misguided followers,” says Bhikkhu Schober, a music publisher in Boulder Colorado. In 1984, he stayed in Oregon for three months as a paying guest worker.

As matters began to spin out of control, she and her followers fled to Europe in September 1985. Soon after, Rajneesh held a press conference, in which he labelled Sheela and her associates a “gang of fascists” and accused them of arson, wire-tapping, mass poisoning and attempted murder. On October 23, 1985, a federal grand jury indicted Rajneesh and several other disciples with conspiracy to evade immigration laws. He was arrested and was extradited from the US to India on November 17. In January 1987, he set up the commune in Pune again and took up the title of Osho.

In October 1986, Sheela was arrested in Germany and extradited to the US. She was sentenced to 20 years in prison. She got a reprieve in 29 months for good behaviour. She went to Geneva, where she married Swiss citizen, Urs Brinstiel, and now runs two retirement facilities for the infirm.

Schober calls Rajneeshpuram “a great but impossible utopian dream and experiment for a better society of love and meditation. It failed because of the ego of the people running it, in particular Sheela.” What was this better society supposed to be? “My vision of a new world, the world of communes, means no nations, no big cities, no families, but millions of small communes spread all over the earth in lush green forests, in mountains, on islands,” Osho had said. He called a commune “a declaration of a non-ambitious life, of equal opportunity for all. But remember my differences with Karl Marx: I am not in favour of imposing equality on people because that is a psychologically impossible task.”

Located in Lane Number 1 of Koregaon Park, the 28-acre main Osho Meditation Resort today is a far cry from its former, cocky self. It sees about 400-odd visitors a day on an average. “This is not an ashram, people don’t live here,” says Ma Sadhana. While she insists that the interest in Osho has only increased over the last few years, the number of visitors has been dropping, say regulars. An old-timer, Swan Treasure, says it is probably because of the prohibitive cost of living at the resort: the minimum is a seven-day residential programme that sets one back by Rs 45,400, not inclusive of meals. “We don’t want the crowds here. Look at the high standards we maintain. Moreover, Osho never looked at meditation as something you do for free,” says Ma Sadhana. She has watched the documentary and says it has nothing new to offer. “Osho loved controversy. He used to say, love me or hate me but don’t ignore me. Wherever there was Osho, there was misconception and controversy,” she says.

– With inputs from Alifiya Khan

May 02: Latest News

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05