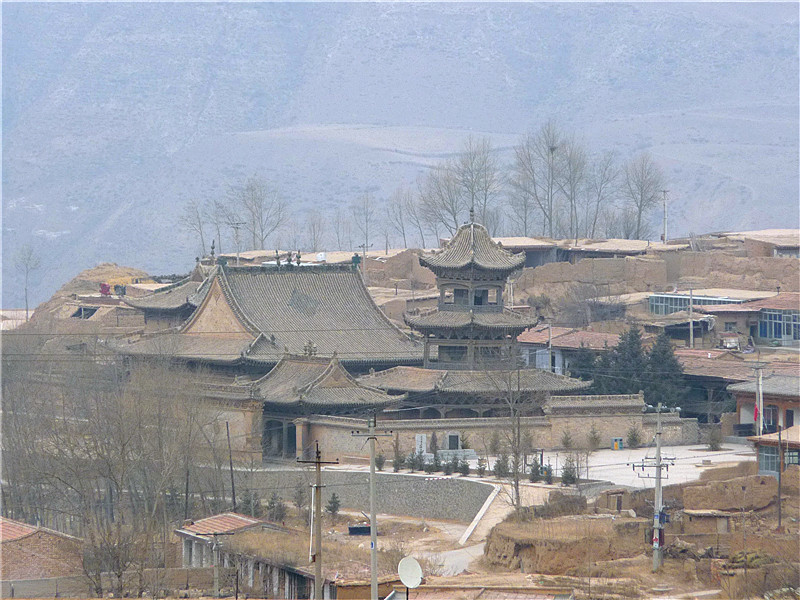

Overview from northwest (http://shuizhongxumin.blog.163.com/blog/static/132280274201311167350342)

Area approx. 4,500 sqm

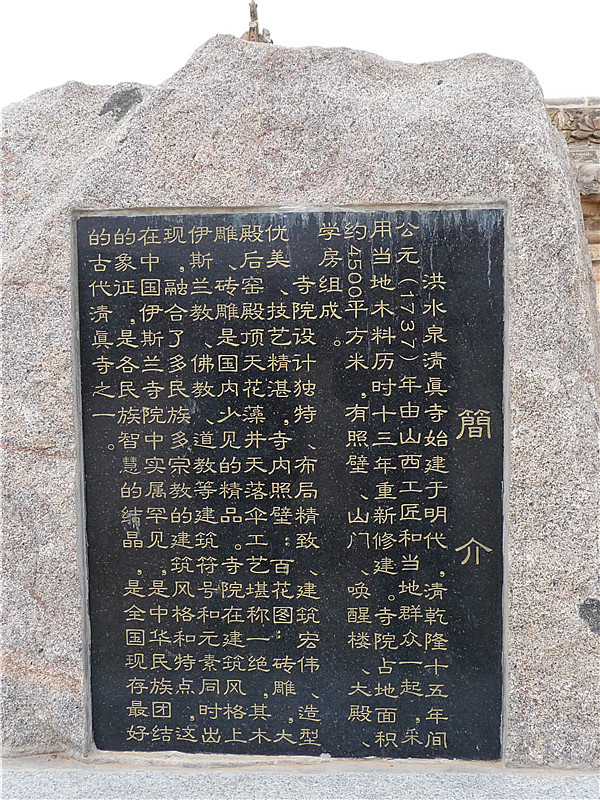

Established in the Ming dynasty, reconstructed in 1737 (Qing dynasty)

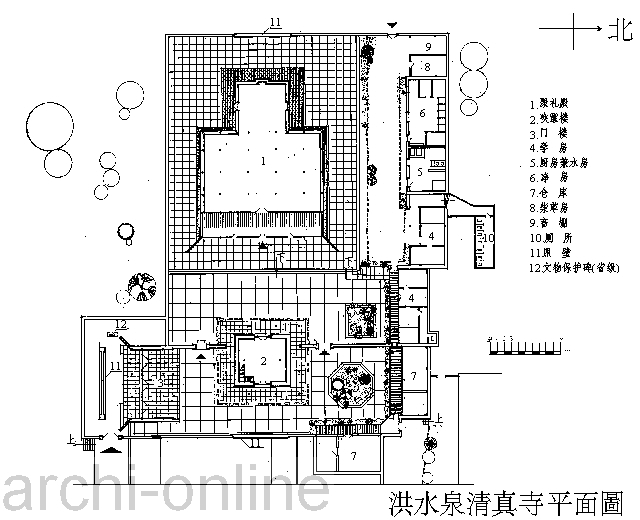

Hongshuiquan, Huangzhong, Qinghai Province

Layout

Overview from southeast (http://shuizhongxumin.blog.163.com/blog/static/132280274201311167350342)

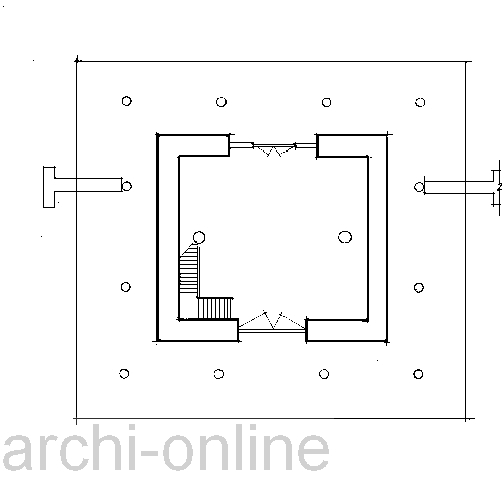

Site plan (Sun 2009: 365)

The main entrance faces south. Upon entering the mosque, however, the axis of the site turns ninety degrees to the left and starts to run east-west, instead of north-south which was the norm for traditional Chinese architecture. The central tower, functioning as a minaret, is located at the heart of the building complex and stands as the vantage point; its centrality, height, and imposing structural sophistication parallel to those of the pagoda in a Buddhist monastery.

The prayer hall behind the tower is the largest building at the site. Its plan looks like a large square with a smaller square attached to the back. The multi-columned design is certainly derived from typical mosque plans in the West such as the hypostyle hall of the Great Mosque at Cordoba. The spacious area would allow the faithful to pray as equals in front of the one true god. The mihrab or prayer niche, here accentuated by enlarging the recessed area on the wall into a separate room, allows not only for a greater depth of the hall (hence creating a stronger directional “pull” toward qibla and Mecca), but also a ceiling “dome” to be added above. The accentuation of the “holy of holies” is manifest architecturally both inside and out; the resultant irregular, bell-shaped enclosure of the wall indicates hybridity, foreign influence, and cultural adaptation.

Modern introduction on site (http://shuizhongxumin.blog.163.com/blog/static/132280274201311167350342)

Notable Structures

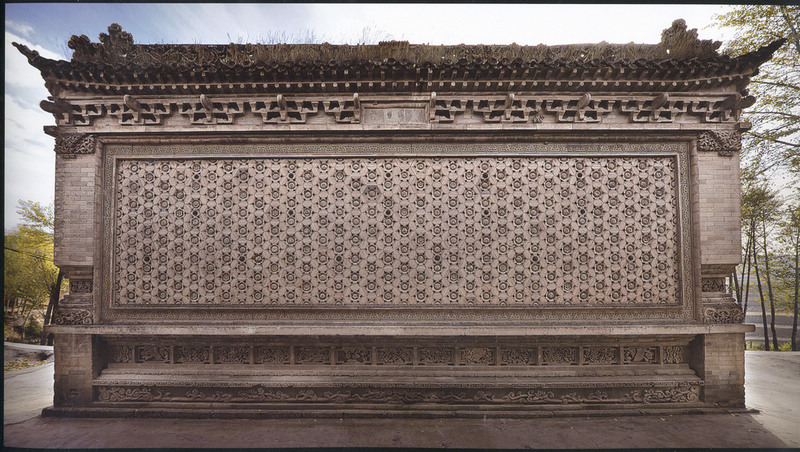

Screen Wall

Tessellated floral patterns carved on screen wall (http://www.lyxfx.com/jingdian/%E9%9D%92%E6%B5%B7%E6%B4%AA%E6%B0%B4%E6%B3%89%E6%B8%85%E7%9C%9F%E5%A4%A7%E5%AF%BA.html)

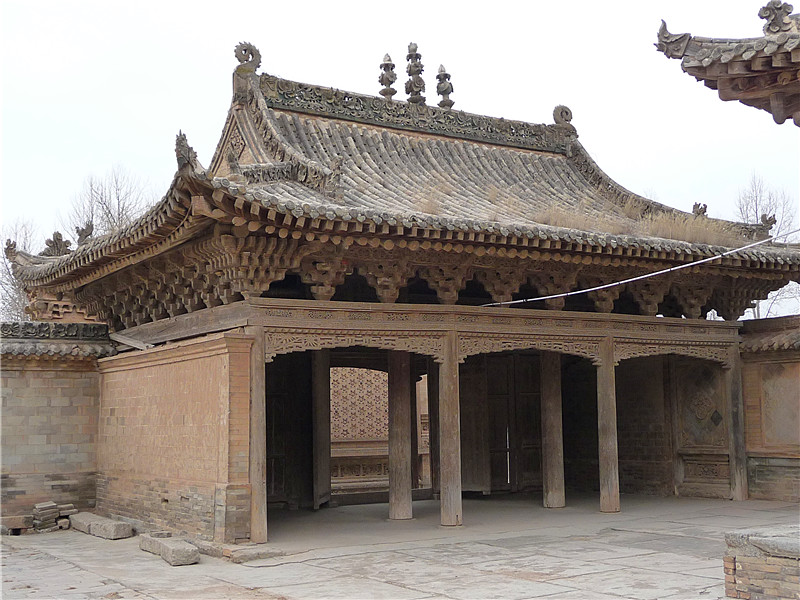

Gatehouse

Entrance to the mosque, with the screen wall at the front and the Waking Tower behind (http://zy.zwbk.org/index.php/%E6%96%87%E4%BB%B6:994064.jpg)

Back of gatehouse (http://shuizhongxumin.blog.163.com/blog/static/132280274201311167350342)

Section of gatehouse (http://www.desinia.tw/monuments/pdetail.php?id=2Q15_07)

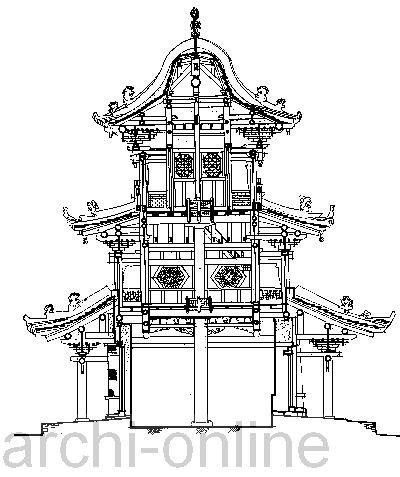

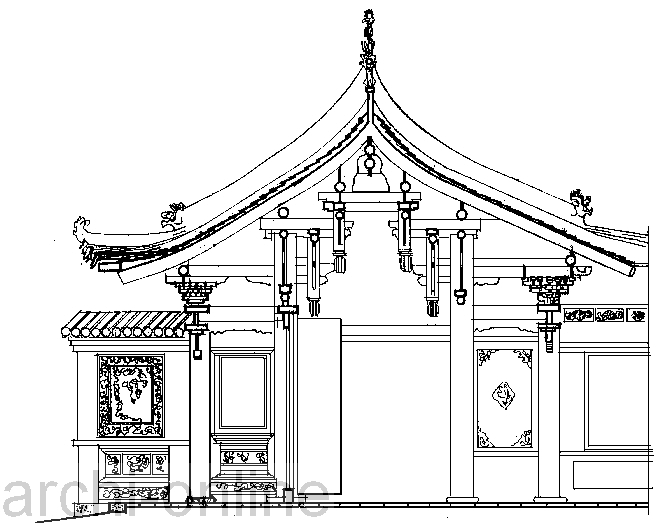

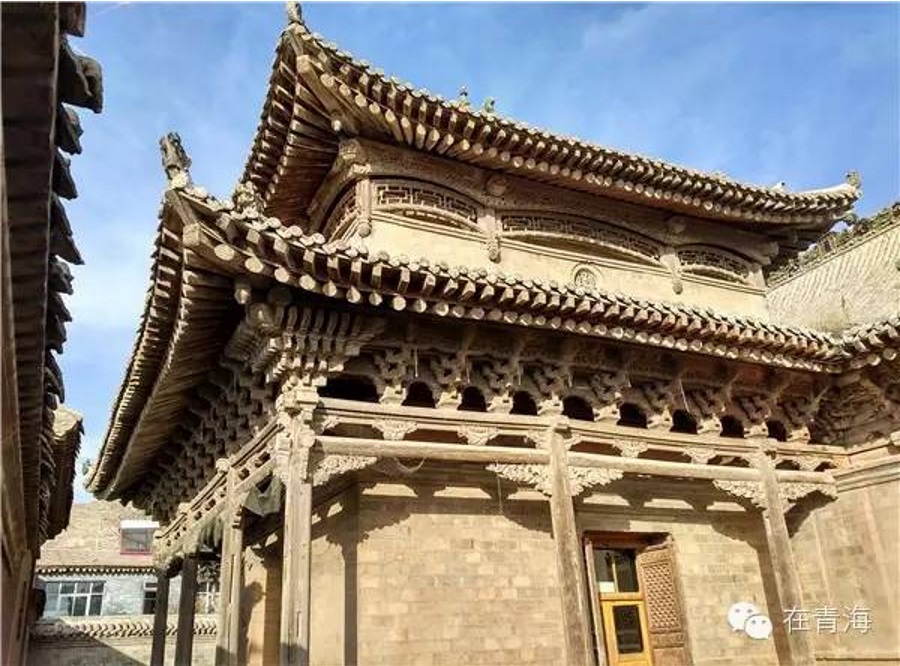

Huanxinglou (Waking tower)

Front elevation (http://zy.zwbk.org/index.php/%E6%96%87%E4%BB%B6:994069.jpg)

The three-storied tower is rectangular on the ground and hexagonal on the second and third levels. The brackets include diagonal (45 degrees) members and conjoined sets.

Detail of elevation (http://shuizhongxumin.blog.163.com/blog/static/132280274201311167350342)

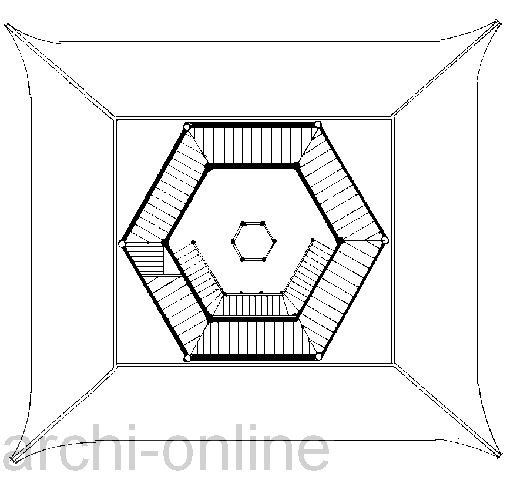

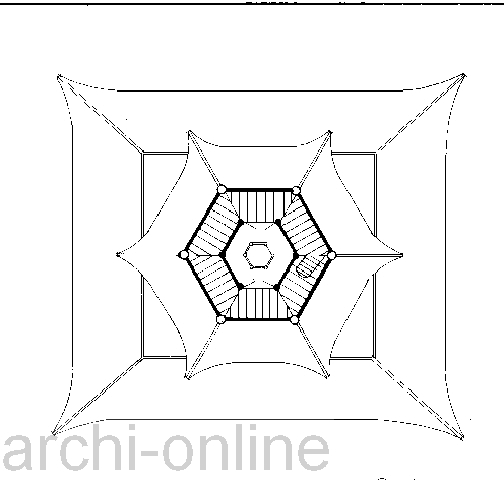

Plan of ground level (http://www.desinia.tw/monuments/pdetail.php?id=2Q15_09A)

Plan of 2nd level (http://www.desinia.tw/monuments/pdetail.php?id=2Q15_09B)

Plan of 3rd level (http://www.desinia.tw/monuments/pdetail.php?id=2Q15_09C)

Prayer Hall

Front elevation of Prayer Hall (http://shuizhongxumin.blog.163.com/blog/static/132280274201311167350342)

Mihrab in prayer hall (http://www.360doc.com/content/16/0106/22/1417717_526026206.shtml)

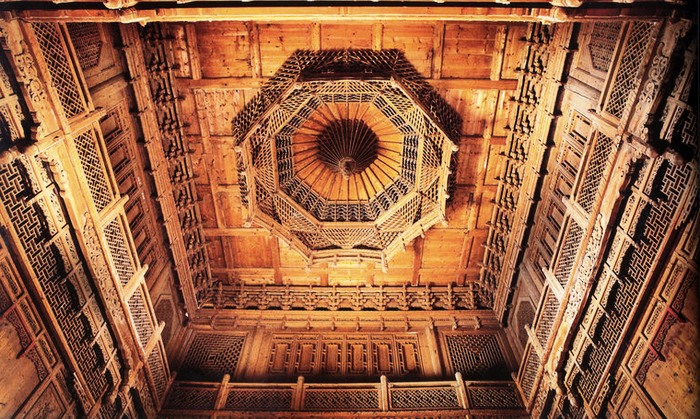

The wall of mihrab room is covered by exquisite woodwork from floor to ceiling. The woodwork is divided into lower and upper registers, as if the interior is two-storied. The lower register contains long, narrow “screen panels” full of carvings of floral patterns and Chinese characters. It transitions to the upper register by a continuous band of suspended elements–the hanging posts, lintels, and balustrade–which suggests cornice and balcony. Up above, the four walls are covered with panels of doors and windows in small scale and with geometric patterns, which recall the miniature douba zaojing (octagonal cupola) described in the Yingzao fashi, perhaps even the tiangong louge motif. This group of small doors and windows gives way to a layer of bracket sets at the top, where everything turns horizontal.

Coffered ceiling and umbrella cupola above mihrab (http://www.lyxfx.com/jingdian/%E9%9D%92%E6%B5%B7%E6%B4%AA%E6%B0%B4%E6%B3%89%E6%B8%85%E7%9C%9F%E5%A4%A7%E5%AF%BA.html)

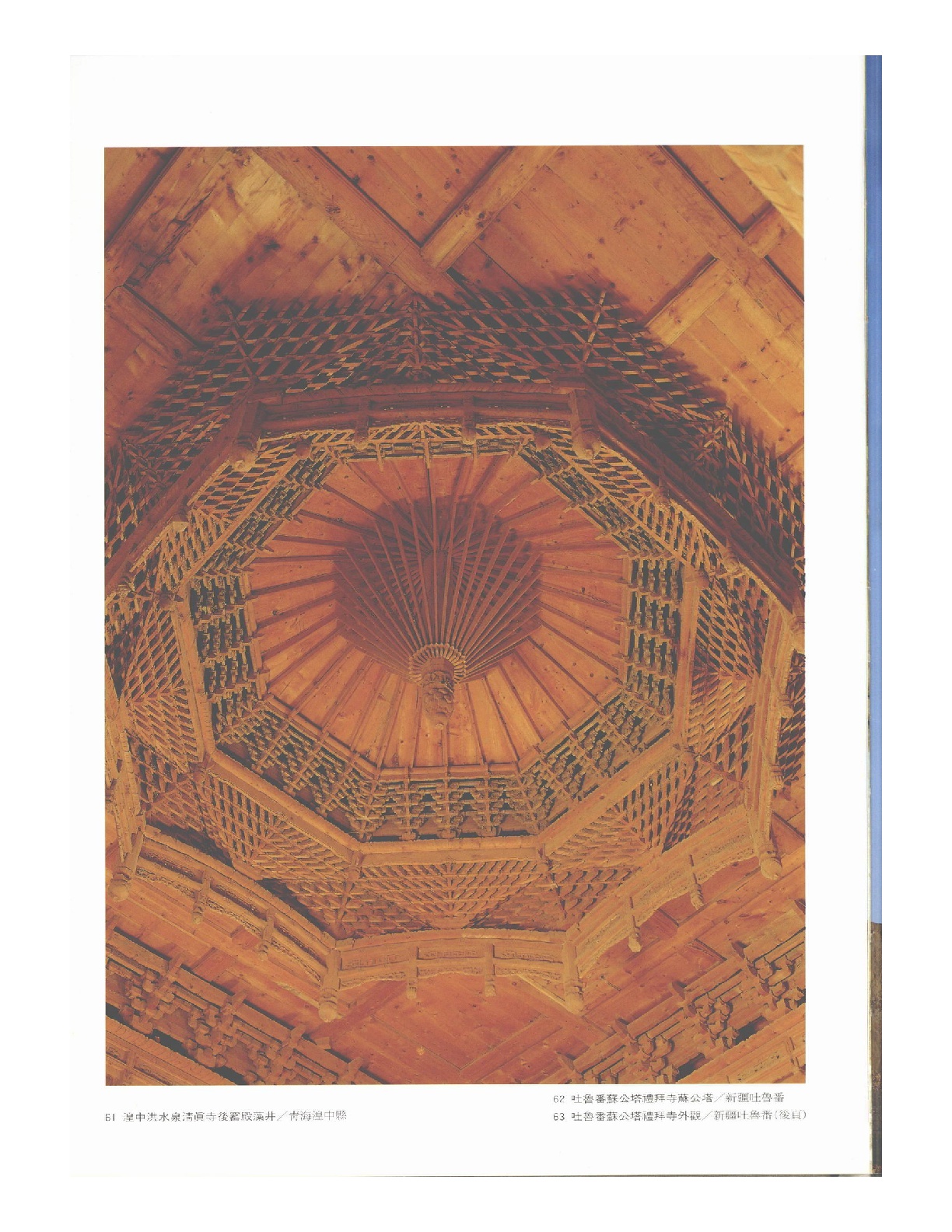

The ceiling, divided into a seven-by-seven (?) grid, features in the middle a one-of-the-kind zaojing (dia. 2 m) in Chinese architectural history. Nicknamed “tianluosan” or celestial umbrella, it is composed of three levels of octagons connected with bracket sets and thin, interlaced wooden ribs. The rim is ended with hanging posts, lintels, and carved panels (huaban); the center is a suspended “pendulum” which gives rise to the visual simile of an umbrella’s handle. In fact, the pendulum has always been an important and distinctive feature of the zaojing since at least the third century CE when it was mentioned in multiple texts.

Umbrella cupola (Qiu 1993: pl. 61)

The pendulum could have been an inverted lotus bud, in which case the coffer would be imagined as a celestial well with heavenly water to subjugate fire, the greatest enemy of all wooden buildings. The lotus is certainly a Buddhist symbol as well, just as the umbrella or baldachin; and by the time when this mosque was built, these Buddhist symbols had been in China long enough that they became stock images in the carpenters’ vocabulary. However, in a Chinese zaojing the well is usually recessed, not suspended. The exotic feeling might have resulted further from the total lack of the use of pigment, which is seldom if ever seen. The exposure of the original wooden texture and hue successfully diverts one’s attention to the innate beauty of materiality and geometry, which is in line with the ideals of Islamic art.

Is the zaojing here meant to be a simulate dome or cupola? Its crisscrossing ribs does recall, to a certain extent, the ribbed domes at Cordoba. Local people speak of it as originally designed to be a turnable and “foldable” device for ventilation. The idea of a turnable ceiling is not unheard of in Chinese architectural history; it was most often associated with mingtang–the legendary cosmic house and ritual seat of power for the Son of Heaven–and historical records show that automated turning devices (probably resembling armilary spheres) were installed in the ceilings of the mingtang of the Northern Wei and Tang dynasties.

Cross-ridged gabled roof atop the back end of prayer hall, directly over the umbrella cupola (http://www.360doc.com/content/16/0106/22/1417717_526026206.shtml)

Exterior view of back end of prayer hall, where the mihrab is located (http://www.360doc.com/content/16/0106/22/1417717_526026206.shtml)

The compound, bell-shaped plan of the hall gives rise to a compound form of the overall architecture: the larger square is covered by a single-eaves hip-and-gable roof; the smaller square, on the other hand, has a skirting eaves at the same level as the roof of the larger square, and, above that, a “clerestory” level or mezzanine (marked by arching lintels on elevation) with a four-sloped square roof crowned with a cross-ridged top consisting of four gables, each of which is covered by a triangular hatch-patterned “vent” or lattice screen.

References

- Liu Zhiping 劉致平. Zhongguo Yisilanjiao jianzhu 中國伊斯蘭教建築 (Islamic Architecture in China). Beijing: Zhongguo jianzhu gongye chubanshe.

- Qiu Yulan 邱玉蘭. 1993. Yisilanjiao jianzhu: Musilin libai qingzhensi 伊斯蘭教建築:穆斯林禮拜清真寺 (Islamic Architecture: Mosques for Musilm worship). Beijing: Zhongguo jianzhu gongye chubanshe. 164.

- Steinhardt, Nancy. China’s Early Mosques.

- Sun Dazhang, editor. 2009. Zhongguo jianzhu shi. 2nd edition. Vol. 5. Beijing: Zhongguo jianzhu gongye chubanshe. 365.