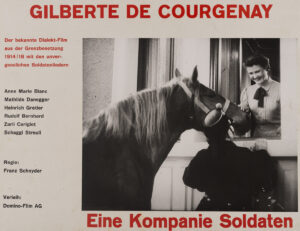

A waitress becomes a legend

During World War I Gilberte Montavon from Courgenay was a ray of light for Swiss-German soldiers, easing the drudgery of their day-to-day life on the border.

Hanns in der Gand sings the homage to Gilberte. YouTube

This article appeared in the Bieler Tagblatt. It was published in that newspaper on 10 July 2020 under the title “How a waitress became a legend”.

Read here how the legend lived on in World War II.