Straight Shooter

There’s little doubt that trapshooting champ Dennis DeVaux’s aim is true.

May/June 2004 Ed Gray ’67, Tu’71There’s little doubt that trapshooting champ Dennis DeVaux’s aim is true.

May/June 2004 Ed Gray ’67, Tu’71There's little doubt that trapshooting champ Dennis DeVaux's aim is true.

IF THE RULE-MAKERS OF THE Amateur Trapshooting Association were to have their say, a perfect game in bowl ing wouldn't be a dozen straight strikes, it would be 100. A perfect game in baseball wouldn't be 27 straight outs, it would be 81 straight pitches, all of them strikes. And don't even ask them about the NFL's complicated quarterback rating system, where the top score is 157.8. No, they'd say. Perfect is 100. Out of 100. No misses.

Which is just what Dennis DeVaux '7B shot at the 2oo2 Grand American Hand- icap, besting 3,815 competitors in the country's most prestigious trapshooting event, held every year since 1899 in Van- dalia, Ohio. DeVaux's perfect 100 didn't even win—it got him into a shoot-off with two others who had also gone 100 straight. It took him two more perfect rounds of 25 each to eliminate them, one in each round. And on top of that, the tournament is a handicap event; the higher a shooter is rated, the farther back from the "trap"—the device that hurls the fastflying clay birds away from the shooter-he or she has to stand. DeVaux had to shoot all his targets from the maximum distance of 27 yards back. The other two shooters were rated 22 and 22.5—they got to stand five yards closer, a huge advantage in trying to hit what is essentially a 4-inch-wide Frisbee rocketing away at more than 40 mph. In the 103 years of the tournament only three other "27-yarders" have ever won the tournament with 100 straight, and none of them had gone into a shoot-off. It was an astonishing feat. The Grand American is so difficult that no one, regardless of handicap, has ever won it twice.

biology and played intramural basketball (he's 6-foot-4) and baseball. "I'm still a ra- bid Red Sox fan," he says from his home in Thetford Center, Vermont, where the wall of his den is covered with his winners plaques. One of the earliest is from the 1977 Collegiate Nationals, which he won his junioryear, as captain of the Big Greens five-man varsity that came in fifth out of 28 teams. The next year he finished second out of 270 to lead a team that included Errol Springer '7B, Scot Brewster '79, Brad Westpfahl '78 and Will Warm 'BO (now Will Hale) to the national title, edging archrival Trinity of Texas by one target with a team score of 927 out of a possible 1,000. DeVaux might. He's been a 27-yard "back-fencer" since he was 17, the year before the Norwich, Vermont, natives freshman year. At Dartmouth he majored in

Trapshooting at Dartmouth had a relatively short life span and it was no coincidence that DeVaux found himself in the high-achieving middle of it. His father, Bill, was the coach and provider of its home range: The trap field behind the gun shop he owned and operated across the river at Goodrich Four Corners in Norwich. Started in the 1960s by Jim Schwedland '48 as a physical-education credit program run by the Outing Club, the activity became popular enough by the early 1970s to be upgraded to a varsity sport, a status it held until declining in- terest and budget cuts ended its run in the early 1980s.

"I was saddened to see it dropped," says DeVaux. "I know that I really developed and honed my competitive skills in the sport during those years. But I understood the reasons, notably funding. Even when it was active, the students on the team had to pay for most of their practice rounds. That was a challenge for some and always contributed to less participation."

How hard is trapshooting? That depends on how good you want to be. Like golf, the basics can be learned over the course of a few lessons at any number of clubs, and the result can be a relaxed lifetime of weekend matches where you try to shoot a bit better than the others in your foursome or "squad" (five shooters taking turns behind the same trap). If you wanted to enter tournaments and be more competitive, then the golf equivalent of a registered trap shoot would consist of 100 par-three approach shots taken from five different sets of tees and required to land an easy one-putt from the flag. At DeVaux's level, you'd be swinging from 200 yards back while competing against others hitting from the forward tees. And if you're not going to land within 10 feet of the cup 97 times out of 100, you might as well stay home. Or be content with losing.

But unlike Olympic track or above-the-rim basketball, to get to the top level you don't have to be born with genetic gifts—DeVaux counts himself a "fair" athlete, and he wears glasses. What you will need is the ability to concentrate and a willingness to practice. And practice. And practice.

The sport is all about precision and speed, with an imposed factor of unpredictability. The motor-driven trap it- self is hidden from the shooter s view, in a ground-level knee-high "house," and oscillates continuously while it waits for the shooter to call, "Pull!" at which point it ejects a 4 5/8-inch clay target at 41 mph at whatever angle the machine was on when the "bird" was called for. Two-and-half seconds later the bird will either be "dead" (broken by the shooter) or "lost" (settling to the ground 50 yards away, missed by the shooter).

The rules prescribe a pie-slice-shaped "legal flight area" that keeps the clay targets out in front of the shooter and away from the audience. The five shooters in a squad take turns calling "Pull!" from their handicapped firing points on five lines radiating out behind the trap—with the half-yard-increment firing points on each line beginning at 16 and ending at 27 yards behind the trap, the "back fence" where DeVaux and the other top-rated shooters stand. On each pull a shooter has about a second and a half to locate the bird, track it with his shotgun and pull the trigger, chasing the fragile little disk with an ounce of tiny lead pellets punched into 780-mile-an-hour pursuit by a couple of drams of gunpowder.

The hoped-for result is a broken bird, either slanting away in several jagged pieces or vanishing in a sudden puff of black dust, depending on how many of the 350 or so pellets—by then rapidly spreading and losing velocity— actually hit it. At the usual point of im- pact, about 10 yards out from the trap, the spreading "shot string" of pellets is 15 to 18 inches in diameter and several feet long, a pattern that might seem to allow for a fair margin of error before you realize that at 1,000 feet per second, the string is going to flash past the bird in several hundredths of a second.

Depending on which position the shooter is firing from, what direction the bird takes and how hard and 'from where the wind is blowing, a shooter must point his shotgun anywhere from di- rectly at the bird to as much as three feet in front of it in order to make a hit. It takes good early instruction—and all that practice—to do that with real consistency. To win the Grand American Handicap in 2002, it took perfection. Happily for DeVaux, he had them all, right when he needed them.

He didn't have them last year, at the 2003 tournament. "I did experience something like a 'sophomore slump,'" he says. '!And it seemed odd to me. I've par- ticipated in the tournament for over 30 years and I didn't think being the return- ing champion would have that much ef- fect on me, especially since I had been shooting well in other tournaments that summer leading up to it. Maybe winning it did take some of the hunger out of my system for a while. But you do have a way of getting hungry again."

DeVauxis hungry again. Between last year's Grand American and this summers, as he has every year for three decades, he will have fired another 10,000 rounds, practicing on Thursday nights and com- peting on summer weekends. In August he'll once again drive out to the greatest tournament of them all, trying to become the only two-time winner of the most coveted title in the sport, taking his targets one at a time as he shoots for an even rarer accolade: If he does win, some will certainly call him the greatest shooter of them all. a

Best Shot The shooter, here with hiscustom-made Italian gun, has been winning titles since his undergraduate days.

ED GRAY has edited and written aboutfield sports since 1975, when he and his wife,Rebecca, founded Gray's Sporting Journal. They live, and shoot, in Lyme, New Hampshire.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Great Disconnect

May | June 2004 By ED GRAY ’67, TU’71 -

Feature

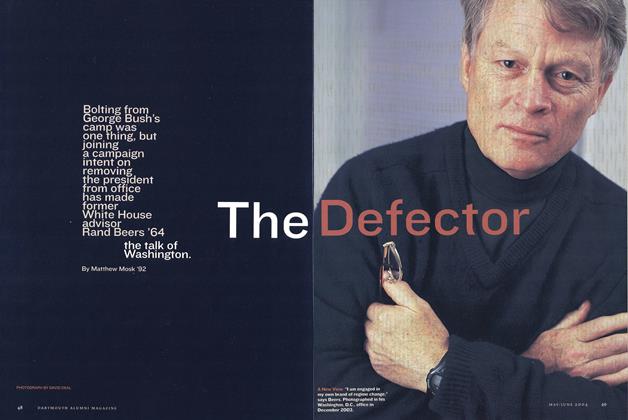

FeatureThe Defector

May | June 2004 By Matthew Mosk ’92 -

Feature

FeatureYou Can’t Always Give What You Want

May | June 2004 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

Feature

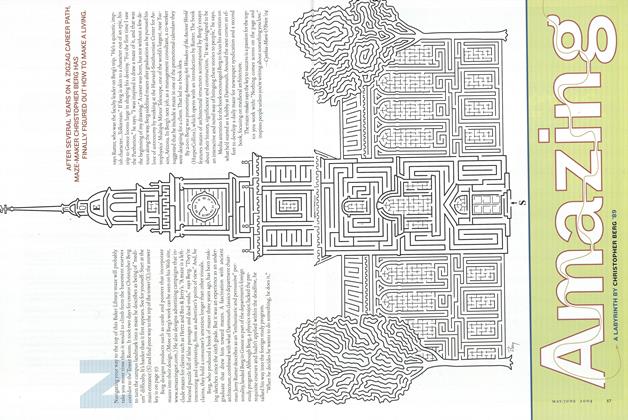

FeatureAmazing

May | June 2004 By Cynthia-Marie O'Brien '04, CHRISTOPHER BERG '89 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Alumni Opinion

Alumni OpinionIn Praise of Class Notes

May | June 2004 By James Zug ’91

Sports

-

Sports

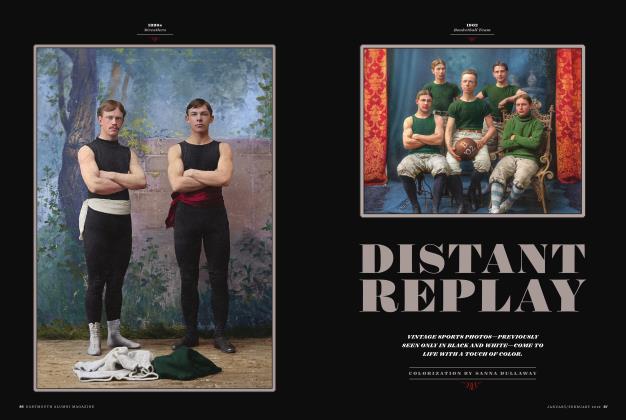

SportsDistant Replay

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2019 -

Sports

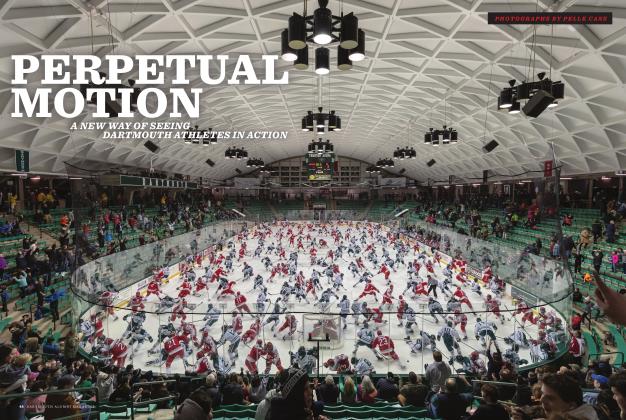

SportsPerpetual Motion

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2019 -

Sports

SportsThe Digital Recruit

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2017 By ADAM BOFFEY -

SPORTS

SPORTS“A Dark Hole”

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2017 By ADAM ESTOCLET '11 -

SPORTS

SPORTSGame Changer

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

SPORTS

SPORTSThree-For-All

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2018 By CHARLES MONAGAN ’72